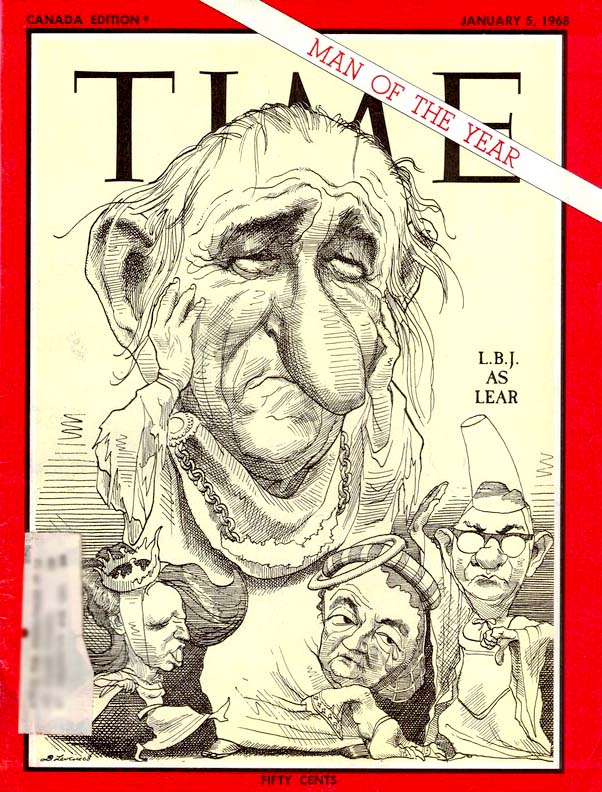

LBJ as Lear

Man Of The Year: Lyndon B. Johnson,

The Paradox of Power

Time Magazine, Friday, Jan. 05, 1968

Time Magazine, Friday, Jan. 05, 1968

Even if the television tube and a ubiquitous Texan had yet to be conceived, the President of the U.S. in the latter third of the 20th century would almost certainly be the world's most exhaustively scrutinized, analyzed and criticized figure. As it is, the power of his office and the Jovian electronic eye ensure that the Chief Executive's visage and voice are available for instant dissection from Baghdad to Bangkok, from factory cafeteria to family living room. Depending on the man and the moment, he may come across as heavy or hero, leader or pleader, preacher or teacher. Whatever his role, in the age of instant communication he inevitably seems so close that the viewer can almost reach out, pluck his sleeve and complain: “Say, Mr. President, what about prices? Napalm? The draft?”

For Lyndon Johnson's 200 million countrymen, the year produced an unprecedented crop of complaints, based largely on the two great crises that came into confluence. Abroad, there was the war in Viet Nam, possibly the most unpopular conflict in the nation's history and the largest ever waged without specific congressional consent. At home, the Negro, more aware than ever of the distance he has yet to travel toward full citizenship, vented his impatience in riots that rent 70 cities in a summer of bloodshed and pillage. The U.S. was vexed as well by violence in the streets, rising costs, youthful rebelliousness, pollution of air and water and the myriad other maladies of a post-industrial society that is growing ever more bewilderingly urbanized, ungovernable and impersonal.

Sense of Impotence.

It was, for many Americans, an end of innocence. The U.S. was still the world's pre-eminent power, still reveled in the accouterments of prosperity, still enjoyed a standard of living far more abundant than that of any other civilization. But 1967 awakened many of its citizens to the fact that conscienceless affluence can not only despoil the environment and drive a deprived underclass to the brink of rebellion; it can also pervade society with a sense of impotence and bring on the loss of unifying purpose.

With so many problems flowing together, the nation was battered by a flood tide of frustration and anxiety. A doubt that in the past had rarely been articulated or even felt crept into the American consciousness: Is the U.S., after all, as fallible in its aims and unsure of its answers as any other great power? Can–and should–the Viet Nam war be won? Can the nation simultaneously allay poverty, widen opportunity, eradicate racism, make its cities habitable and its laws uniformly just? Or will it have to jettison urgent social objectives at home for stern and insistent commitments abroad?

It was increasingly clear that the attainment of all these elusive goals would require, above all, a quality that Americans have always found difficult to cultivate: patience. Yet, as the National Committee for an Effective Congress declared last week, with no exaggeration intended, “America has experienced two great internal crises in her history: the Civil War and the economic Depression of the 1930s. The country may now be on the brink of a third trauma, a depression of the national spirit.”

Man Of The Year: Lyndon B. Johnson, The Paradox of Power, Time Magazine, Jan. 05, 1968.