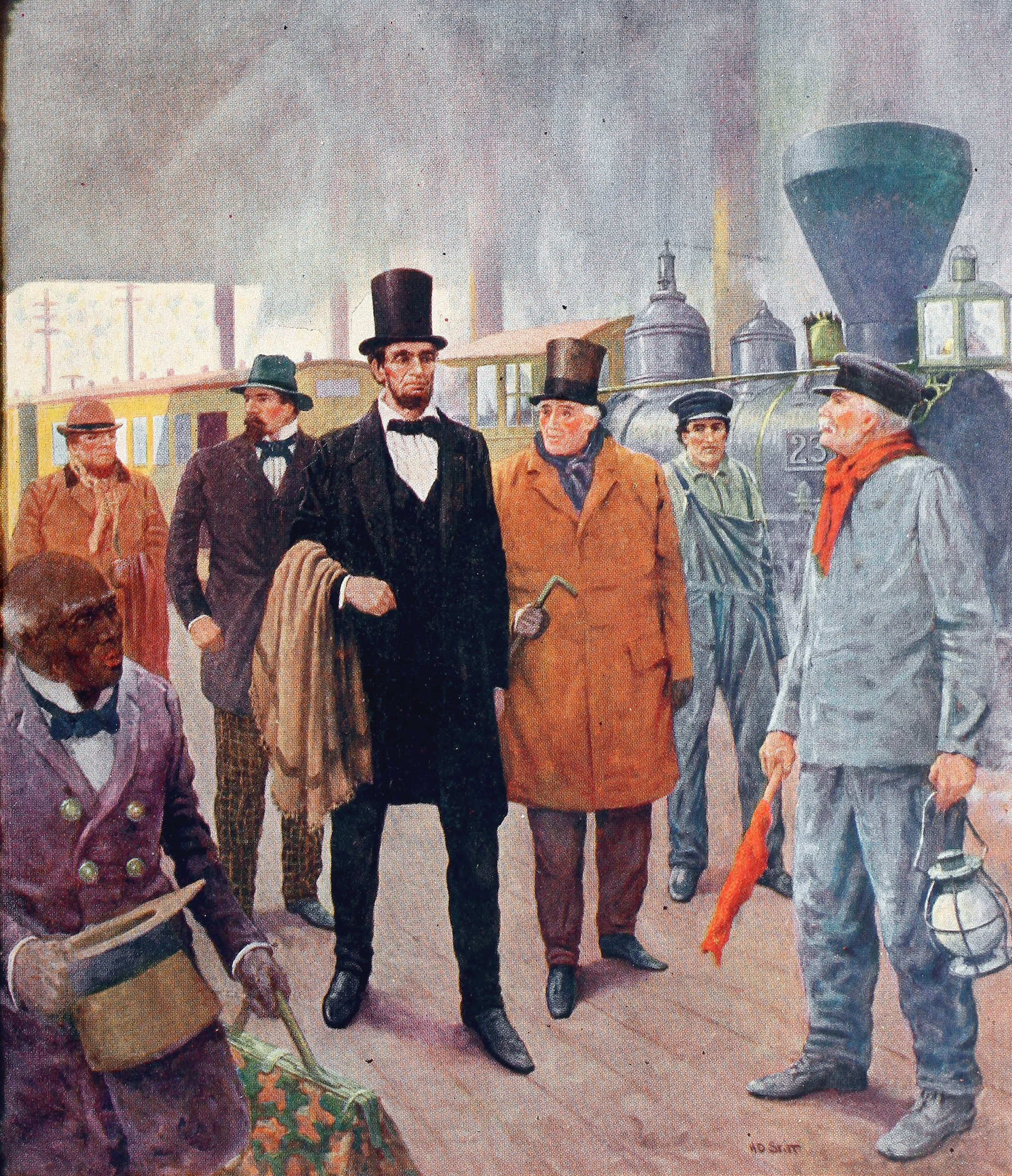

Harrisburg, and the Plans for the Secret Movement to Washington

From "Lincoln and Men of War Times " by Col. A. K. McClure

The two speeches made by Lincoln on the 22d of February do not exhibit a single trace of mental disturbance from the appalling news he had received. He hoisted the stars and stripes to the pinnacle of Independence Hall early in the morning and delivered a brief address that was eminently characteristic of the man. He arrived at Harrisburg about noon, was received in the House of Representatives by the Governor and both branches of the Legislature, and there spoke with the same calm deliberation and incisiveness which marked all his speeches during the journey from Springfield to Washington.

“It was while at dinner that it was finally determined that Lincoln should return to Philadelphia and go thence to Washington that night, as had been arranged in Philadelphia the night previous in the event of a decision to change the programme previously announced. No one who heard the discussion of the question could efface it from his memory. The admonitions received from General Scott and Senator Seward were made known to Governor Curtin at the table, and the question of a change of route was discussed for some time by every one with the single exception of Lincoln. He was the one silent man of the party, and when he was finally compelled to speak, he unhesitatingly expressed his disapproval of the movement. With impressive earnestness he thus answered the appeal of his friends:

“What would the nation think of its President stealing into the Capital like a thief in the night?” It was only when the other guests were unanimous in the expression that it was not a question for Lincoln to determine, but one for his friends to determine for him, that he finally agreed to submit to whatever was decided by those around him.

“It was most fortunate that General Scott was one of the guests at that dinner. He was wise and keen in perception and bold and swift in execution. The time was short, and if a change was to be made in Lincoln's route it was necessary for him to reach Philadelphia by eleven o'clock that night or very soon there-after. Scott at once became master of ceremonies, and everything that was done was in obedience to his directions. There was a crowd of thousands around the hotel, anxious to see the new President and ready to cheer him to the uttermost. It was believed to be best that only one man should accompany Lincoln in his journey to Philadelphia and Washington, and Lincoln decided that Lamon should be his companion. That preliminary question settled, Scott directed that Curtin, Lincoln, and Lamon should at once proceed to the front steps of the hotel, where there was a vast throng waiting to receive them, and that Curtin should call distinctly, so that the crowd could hear, for a carriage, and direct the coachman to drive the party to the Executive Mansion. That was the natural thing for Curtin to do — to take the President to the Governor's mansion as his guest, and it excited no suspicion whatever.

“Before leaving the dining-room Governor Curtin halted Lincoln and Lamon at the door and inquired of Lamon whether he was well armed. Lamon had been chosen by Lincoln as his companion because of his exceptional physical power and prowess, but Curtin wanted assurance that he was properly equipped for defence. Lamon at once uncovered a small arsenal of deadly weapons, showing that he was literally armed to the teeth. In addition to a pair of heavy revolvers, he had a sling-shot and brass knuckles, and a huge knife nestled under his vest. The three entered the carriage, and, as instructed by Scott, drove toward the Executive Mansion, but when near there the driver was ordered to take a circuitous route and to reach the railroad depot within half an hour. When Curtin and his party had gotten fairly away from the hotel, I accompanied Scott to the railway depot, where he at once cleared one of his lines from Harrisburg to Philadelphia, so that there could be no obstruction upon it, as had been agreed upon at Philadelphia the evening before in case the change should be made. In the meantime Scott had ordered a locomotive and a single car to be brought to the eastern entrance of the depot, and at the appointed time the carriage arrived. Lincoln and Lamon emerged from the carriage and entered the car unnoticed by any except those interested in the matter, and after a quiet but fervent “Good-by and God protect you!” the engineer quietly moved his train away on its momentous mission.

“As soon as the train left I accompanied Scott in the work of severing all the telegraph lines which entered Harrisburg. He was not content with directing that it should be done, but he personally saw that every wire was cut. This was about seven o'clock in the evening. It had been arranged that the eleven o'clock train from Philadelphia to Washington should be held until Lincoln arrived, on the pretext of delivering an important package to the conductor. The train on which he was to leave Philadelphia was due in Washington at six in the morning, and Scott kept faithful vigil during the entire night, not only to see that there should be no restoration of the wires, but waiting with anxious solicitude for the time when he might hope to hear the good news that Lincoln had arrived in safety. To guard against every possible chance of imposition, a special cipher was agreed upon that could not possibly be understood by any but the parties to it. It was a long, weary night of fretful anxiety to the dozen or more in Harrisburg who had knowledge of the sudden departure of Lincoln. No one attempted to sleep. All felt that the fate of the nation hung on the safe progress of Lincoln to Washington without detection on his journey. Scott, who was of heroic mould, several times tried to temper the severe strain of his anxiety by looking up railway matters, but he would soon abandon the listless effort, and thrice we strolled from the depot to the Jones House and back again, in aimless struggle to hasten the slowly-passing hours, only to find equally anxious watchers there and a wife whose sobbing heart could not be consoled. At last the eastern horizon was purpled with the promise of day. Scott reunited the broken lines for the lightning messenger, and he was soon gladdened by an unsigned dispatch from Washington, saying, “Plums delivered nuts safely.” He whirled his hat high in the little telegraph office as he shouted, “Lincoln's in Washington.” and we rushed to the Jones House and hurried a messenger to the Executive Mansion to spread the glad tidings that Lincoln had safely made his midnight journey to the Capital.”