Special Dispatch to the New-York Times.

Harrisburg, Saturday, February 23, 1861-8 A.M.

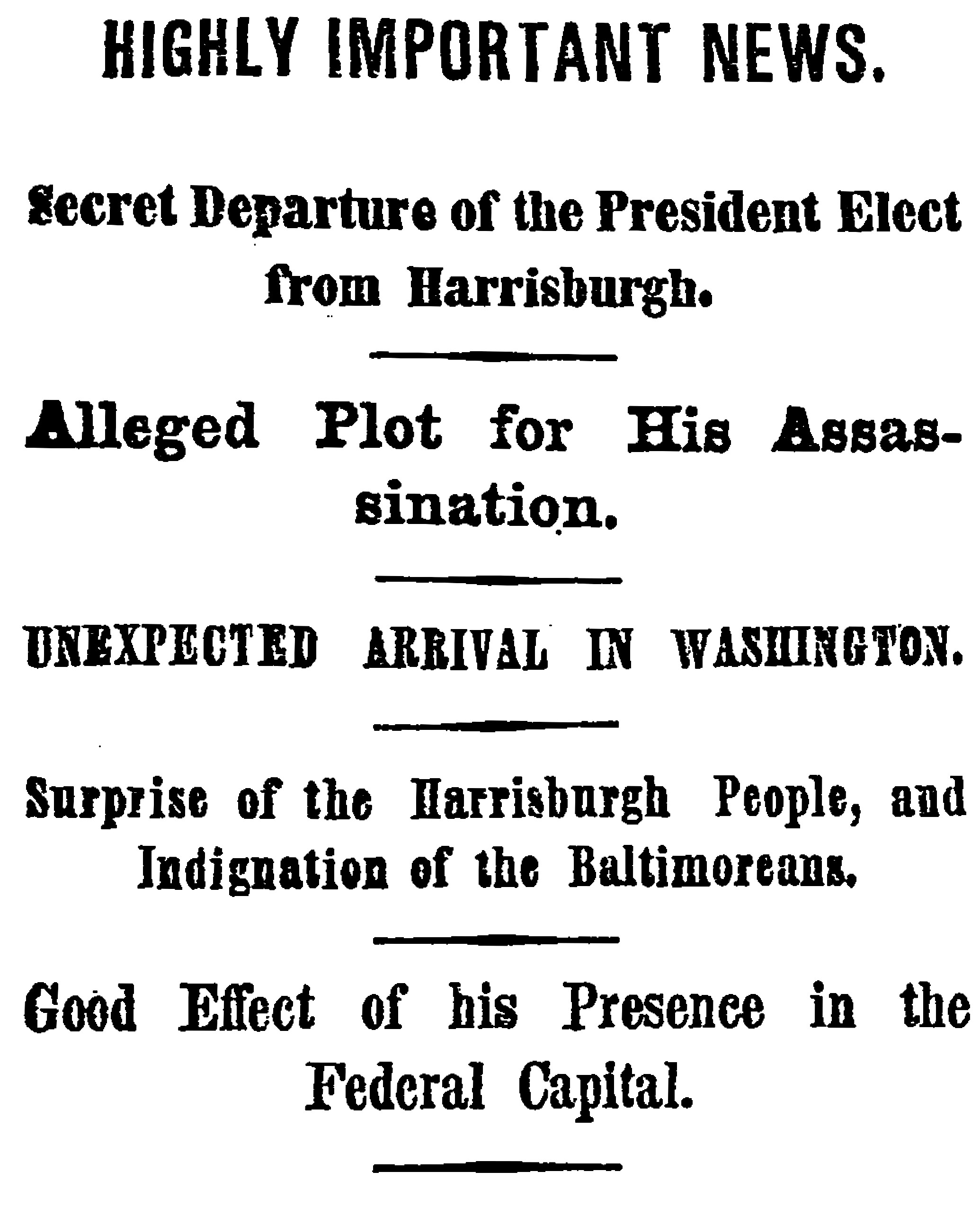

Abraham Lincoln, the President-elect of the United States, safe in the capital of the nation. By the admirable arrangement of General Scott, the country has been spared the lasting disgrace which might have been fastened indelibly upon it had Mr. Lincoln been murdered upon his journey thither, as he would have been had he followed the programme as announced in the papers and gone by the Northern Central Railroad to Baltimore. On Thursday night after he had retired, Mr. Lincoln was aroused and informed that a stranger desired to see him on a matter of life and death. He declined to admit him unless he gave his name, which he at once did, and such prestige did the name carry that while Mr. Lincoln was yet disrobed he granted an interview to the caller. A prolonged conversation elicited the fact that an organized body of men had determined that Mr. Lincoln should not be inaugurated; and that he should never leave the city of Baltimore alive, if, indeed, he ever entered it. The list of the names of the conspirators presented a most astonishing array of persons high in Southern confidence, and some whose fame is not confined to this country alone.

Statesmen laid the plan, bankers indorsed it, and adventurers were to carry it into effect. As they understood, Mr. Lincoln was to leave Harrisburg at nine o'clock this morning by special train, the idea was, if possible, to throw the cars from the road at some point where they would rush down a steep embankment and destroy in a moment the lives of all on board. In case of the failure of this project, their plan was to surround the carriage on the way from depot to depot in Baltimore, and to assassinate him with dagger or pistol shot. So authentic was the source from which the information was obtained that Mr. Lincoln, after counselling with his friends, was compelled to make arrangements which would enable him to subvert the plans of his enemies. Greatly to the annoyance of the thousands who desired to call on him last night, he declined giving a reception. The final council was held at eight o'clock.

Mr. Lincoln did not want to yield, and Colonel Sumner actually cried with indignation; but Mrs. Lincoln, seconded by Mr. Judd and Mr. Lincoln's original informant, insisted upon it, and at nine o'clock Mr. Lincoln left on a special train. He wore a Scotch plaid cap and a very long military cloak, so that he was entirely unrecognizable. Accompanied by Superintendent Lewis and one friend, he started, while all the town, with the exception of Mrs. Lincoln, Colonel Sumner, Mr. Judd, and two reporters who were sworn to secrecy, supposed him to be asleep.

The telegraph wires were put beyond reach of anyone who might desire to use them.

At one o'clock the fact was whispered from one to another, and it soon became the theme of the most exited conversation. Many thought it was a very injudicious move, while others regarded it as a stoke of great merit. The Special train leaves with the original party, including the Times correspondent, at nine o’clock.