The Sunday Star, Washington, DC, September 05, 1926

Family Version of Story of Barbara Frietchie

Given at Frederick

Light Thrown Upon Facts Behind Incident Recorded by Whittier

Up rose old Barbara Frietchie then, Bowed with her fourscore years and ten;

Bravest of all in Frederick town, She took up the flag the men hauled down;

In her attic window the staff she set, To show that one heart was loyal yet.

Up the street came the rebel tread, Stonewall Jackson riding ahead.

Under his slouched hat left and right He glanced: the old flag met his sight.

“Halt!”— the dust-brown ranks stood fast. “Fire!”— out blazed the rifle-blast.

It shivered the window, pane and sash; It rent the banner with seam and gash.

Quick, as it fell, from the broken staff Dame Barbara snatched the silken scarf;

She leaned far out on the window-sill, And shook it forth with a royal will.

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country's flag,” she said..

—From Whittier's Poem.

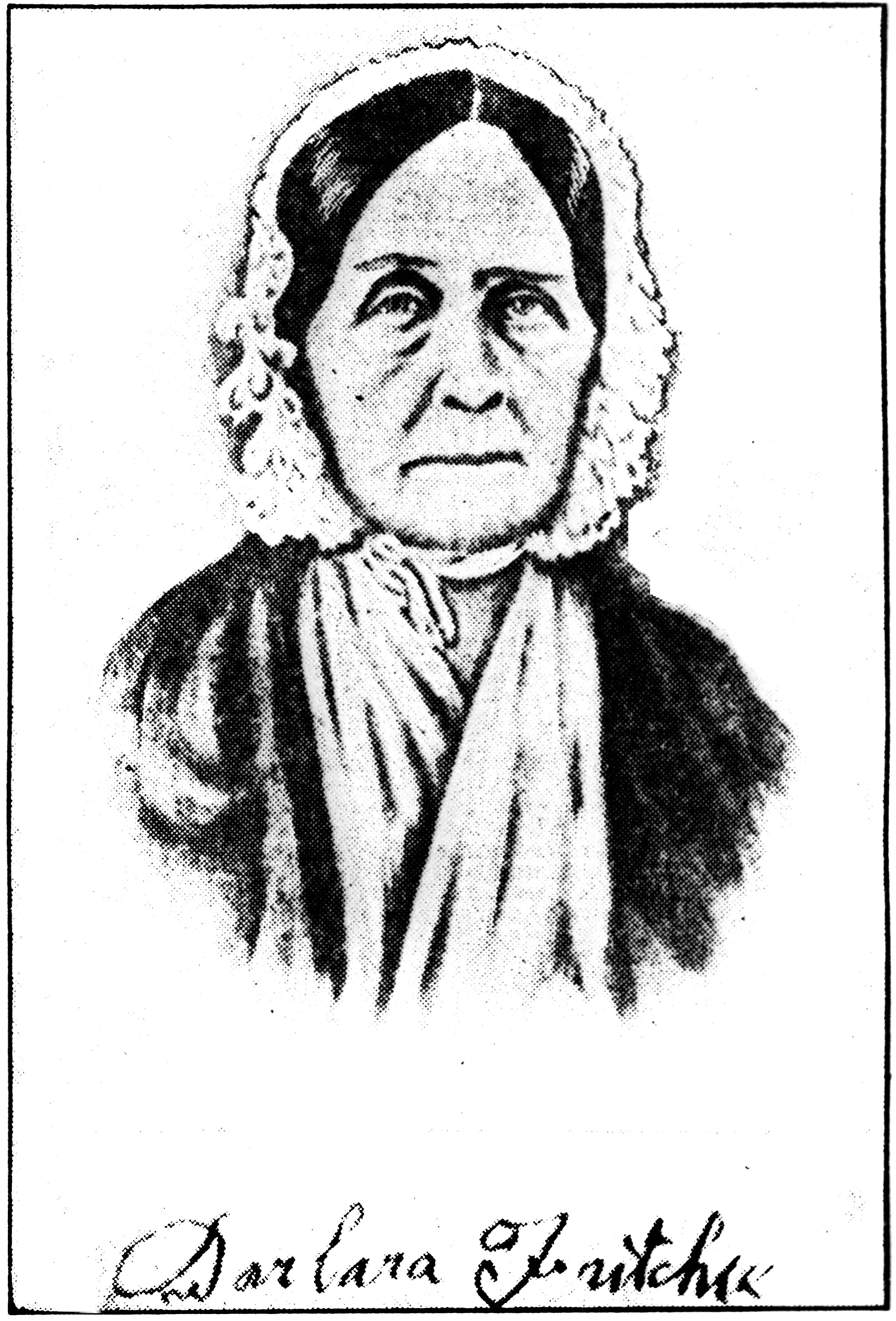

WHITTIER may have exercised poetic license and made her fame, but the town in which she lived is Barbara Frietchie's town. It has produced other noted citizens, it is replete with history at every turn, there are lovely old Georgian houses along its streets, it was named in 1745 for Frederick,— Prince of Wales, the father of George III, but the most picturesque thing it has ever produced was a tiny little old lady of 96 who hobbled to her front door and shook the flag of her country in the faces of the invading Confederate Army. She stimulated the imaginations of the citizens of Frederick, Md., and then of the people of the United States, and her place in history is fixed.

Her face looks out at you from picture post cards in every store in her old home town and from life-size portraits on the walls of public places, and her name is emblazoned from gasoline stations, from chocolate shops, over the door of a hotel from a soft-drink counter and even from a hot-dog stand. On the main thoroughfare through the city a sign on the bridge running over Carroll Creek marks the place where her house stood, and a tiny flag always flutters, whether it rains or shines, over the sign.

It is Impossible to get out of Frederick without knowing that it was the home of the loyal little old lady. Her relatives still live in Frederick, and one of the most patriotic of them today has some of the personal belongings of Barbara Frietchie. “My mother gave them to me because she said I seemed to be more interested in them than any of the other children,” explained Miss Eleanor D. Abbott, the great-great-niece of the famous patriot.

“This is Barbara Frietchie's flag which she waved at the Confederate soldiers at the time they marched through Frederick in 1862”, the incident around which Whittier's poem was written. She also waved it at the Union soldiers when they marched through the city some time later. You see, it is badly framed, the edges being tucked in, but I am almost afraid to have it taken out and reframed, as it might drop to pieces, in the handling.

THE HOME OF BARBARA FRIETCHIE.

Controversy has raged for along time about the incident described so colorfully in Whittier's poem, and Miss Abbott frankly admits that by the time the story of the incident had reached Whittier it had been embellished greatly as to detail. Barbara Frietchie, then 96 years old, didn’t climb to her attic window to set up the staff after all the other Union flags in the city had been taken down; Stonewall Jackson didn’t ride by her house&msash;a perfect alibi having been established for him—and no one ever fired on the flag, much less “shivered the window, pane and sash.” or “rent the banner with seam and gash.”

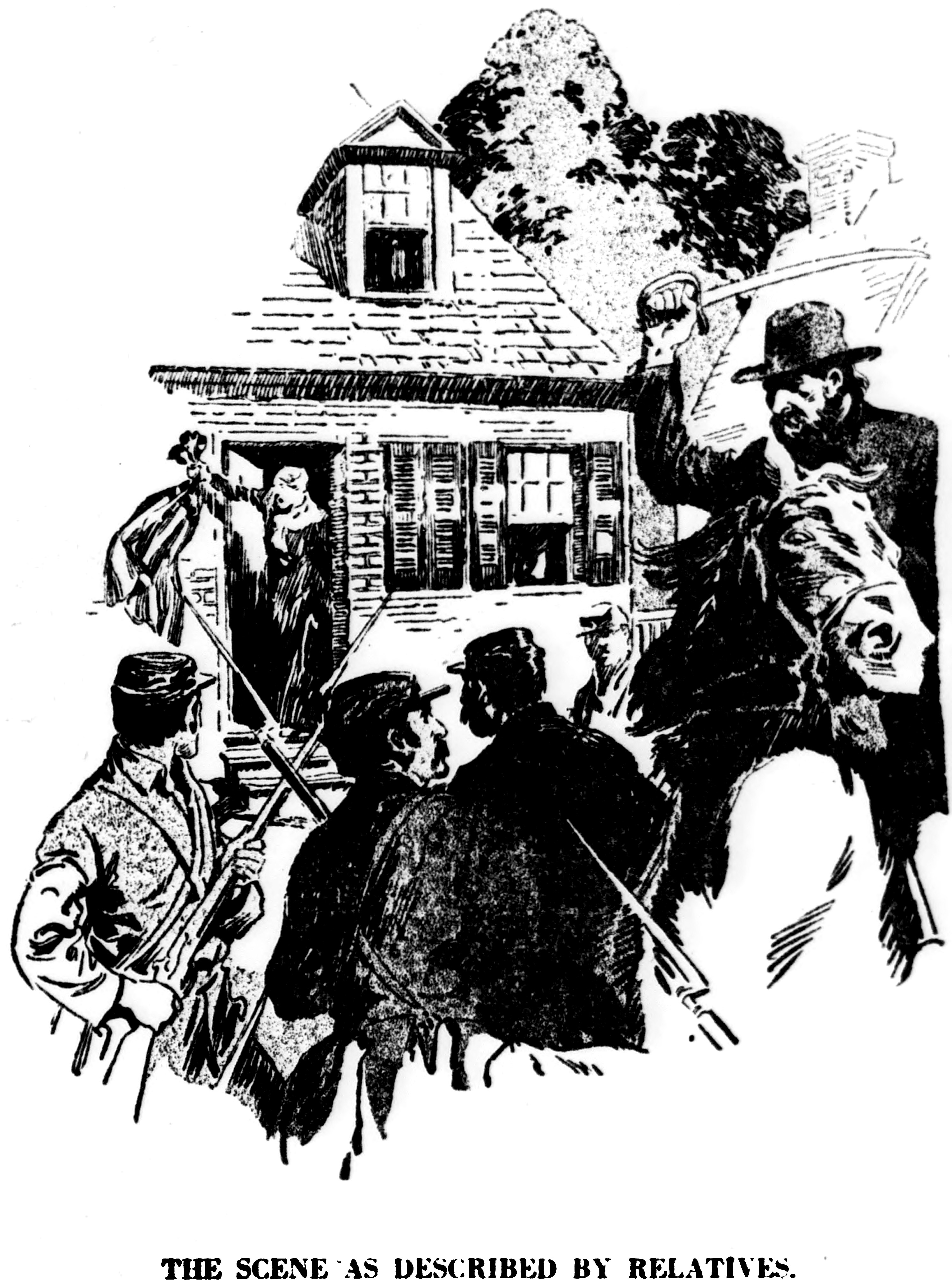

INCIDENT AS DEPICTED IN HISTORIES BASED ON POEM,

BARBARA FRIETCHIE.

Furthermore, she didn't “lean far out on the window sill and shake it forth with a royal will.” It sometimes seems a pity to destroy a beautiful picture, but the truth will out, and this is what Miss Abbott says about it:

“The Confederate forces crossed the Potomac and entered Maryland from Virginia on September 5, 1862. Most of the army camped three miles south of the city, but a large body of soldiers marched through Frederick and camped at Wormans Mill, two miles to the north.

“On the 10th the soldiers who had been encamped to the north re-entered Frederick and marched down North Market street and out West Patrick street past the home of Mrs. Frietchie. No one knew what happened when the soldiers went past the house until some time afterward. Miss Harriet Yoner, a cousin of Barbara Frietchie, was living with her at the time as her companion. Upon coming from the back of the house after the soldiers had passed, Miss Yoner found Mrs. Frietchie quite nervous and excited, but she would not explain except to say: “They tried to take my flag, but a man would not let them, and he was a gentleman.“

“It was not until a number of years later that her family learned exactly what had happened to her.

“It seems that she heard the troops approaching and thinking they were Union soldiers she took her silk flag from between the leaves of the family Bible and stepped to the front door to wave to them. Immediately one of the officers rode up and said, ‘Granny, give me your flag.’

“‘You can’t have it,’ she replied, as she noticed the gray uniforms, but she stood her ground and kept on waving the flag. The officer spoke to his men and they did a ‘turn left,’ facing her. She said she thought they meant to fire on her, but the officer rode a short distance away and immediately returned with another officer, who said to her. ‘Granny, give me your flag and I'll stick it in my horse's head.’ And again she answered, ‘No, you can’t have it.’

“Then one of the men called out, ‘Shoot her damned head off.’ The officer wheeled angrily upon him and said, ‘If you harm a hair of her head I'll shoot you down like a dog.’ Then he turned to the old lady and said, ‘Go on, Granny, wave your flag as much as you please.’

“Not very long ago Mr. Joseph Howe of Worthington. Minn., wrote to me telling me that he had seen Mrs. Frietchie waving the flag to the Confederate soldiers. Mr. James L. Parson, a contractor of Washington, D. C., and a number of others have confirmed these particulars of the incident.

THE SCENE AS DESCRIBED BY RELATIVES.

“Mr. Frank Myers, a captain in the Confederate Army, remembered the incident and wrote, ‘There is more poetry than truth in Whittier's song. As we passed by she (Mrs. Frietchie) came out on the porch and waved her flag at us. Not one of us tried to bother her, and it was not necessary for Stonewall Jackson to say a word.’

“A few days after the above incident the Union forces under Gen. McClellan marched through Frederick and Mrs. Frietchie again got out her flag and waved it at them, but from the window of the front room facing the creek. She did not climb with it to the upper window nor restore it to a staff as described in the poem.

“It seems that the fault of the embellishment of the details of the incident is not entirely to be blamed on Whittier.

“One of the raconteurs of the story reported that the whole Confederate Army was talking about he episode. As nearly as we can trace it, it seems that Miss Ebert, a niece of Mrs. Frietchie, told her cousin, Mr. Ramsburg of Washington, D. C., the story; he in turn told it to a newspaper reporter, and it subsequently appeared in a Washington newspaper. Mr. Ramsburg also told the story to his neighbor, Mrs. E. D. E. N. South worth, the well known authoress, by whom it was sent to Whittier with a note containing the following information:

“‘When Lee's army occupied Frederick, the only Union flag displayed in the city was held by Mrs. Barbara Frietchie, a widow lady of 96 years. Such was the paragraph that went the rounds of the Washington papers last September. Some time afterward, from friends who were in Frederick at the time, I heard the whole story. It was the story of a woman's heroism, which, when heard, seemed as much to belong to you as a book picked up with your autograph on the fly leaf. So here it is.’

“Then she described the cool reception accorded Lee's army as it marched into Frederick and continued:

“‘But Mrs. Barbara Frietchie, taking one of the Union flags, went up to the top of her house, opened a garret window, and held it forth. The rebel army marched up the street, saw the flag; the order was given, “Halt! Fire!” and a volley was discharged at the window from which it was displayed. The flagstaff was partly broken, so that the flag drooped; the old lady drew it in, broke off the fragment, and, taking the stump with the flag still attached to it in her hand, stretched herself as far out of the window as she could, held the Star and Stripes at arm's length, waving over the rebels, and cried out in a voice of indignation and sorrow:

“‘ “Fire at this old head, then, boys; it is not more venerable than your flag.” They fired no more, but passed on in silence, and she secured the flag in its place, where it remained un molested during the whole of the rebel occupation of the city, Stonewall would not permit her to be troubled.’”

Whether Mrs. Southworth is responsible for the “applesauce” spread over the true narrative is not known, but at least Whittier's reputation seems to be stainless. Nevertheless, as soon as he wrote the poem and it was published in the Atlantic Monthly his troubles began. Long before his death he realized that he had written the poem from a much “dressed-up” story, and he wrote countless letters in vindication of his honest, intentions. In answer to an article denying that the poem had any foundation in fact, he wrote: ‘Barbara Frietchie’ was written in good faith. The story was no invention of mine. It came to me from sources which I regarded as entirely reliable. I had no reason to doubt its accuracy then, and I am still constrained to believe that it had foundation in fact. If I thought otherwise I should not hesitate to express it. I have no pride of authorship to interfere with my allegiance to truth.”

In a letter to Miss Abbott's mother, Mrs. Julia H. Abbott, relative to several things, Whittier included the following paragraph: “There has been a good deal of dispute about my little poem, but if there was any mistake in the details there was none in my estimate of the noble character and her loyalty and patriotism.”

And through all the arguments, denials and discussions, there shines the dominant personality of a little old woman, who at 96 years of age, had the courage of her convictions and the “pep” to stand up for them in the face of a whole army of reckless young men who might have made it uncomfortable, if not dangerous,for her.

Barbara Fritchie

It is said that she repeatedly “sassed” Confederate soldiers whenever she saw them and kept her family constantly worrying as to what might happen to her. Her house was near the spring from which the inhabitants of the city obtained their water supply, and soldiers often came to her house to ask for a drinking glass. She always furnished one to Union soldiers, but told the Confederates to drink out of the iron dipper that hung by the spring.

She was born of Pennsylvania Dutch parentage at Lancaster, Pa., on December 3, 1760, and was given as good an education in Baltimore, Md. as could he obtained in her day. She was well read and even during the latter part of her life her mind was clear and alert. She was punctilious about even small things, and one of the treasured possessions of her great-great niece is a note which she wrote out and signed, at 92 years of age, for some money which she borrowed.

MONUMENT OVER GRAVE OF BARBARA FRIETCHIE

IN MOUNT OLIVET CEMETERY, FREDERICK, MD.

The old Hauer family Bible, written in German —Barbara Frietchie was Barbara Hauer before her marriage— is still in existence today. Miss Abbott does not own it, for it was given by a relative to a German woman in the neighborhood who was not related to Mrs. Frietchie. On the flyleaf of this old Bible are recorded most of the important events in the lives of the members of Barbara Frietchie's family.

It is said that she was slight of figure and scarcely of medium height, and that she probably never weighed more than 110 or 115 pounds. Her early days were those of the stirring times during the American Revolution, which probably awoke in her the intense patriotism and loyalty for the flag which marked the latter part of her life. And she must have been a rather vivid personality, for at 40 years of age she married John C. Frietchie, then only 26. which is considered an accomplishment in those days.

(copyright 1926)

Family Version of Story of Barbara Frietchie Given at Frederick, The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., September 05, 1926, Page 2. (PDF)