Western Newspaper Union, 1932

Chief Black Hawk and His “War”

by Elmo Scott Watson

It WAS just 100 years ago that there was being fought in Illinois and Wisconsin what has been called “the most inglorious war, from the standpoint of its military and ‘naval’ operations, in which the United States was ever engaged.” This was the conflict which has a place In our history schoolbooks as “the Black Hawk war” but which scarcely deserves the dignity of that title except that it was a war between two Irreconcilable points of view—that of the American frontiersman and that of the American Indian. From the Indian point of view, Chief Black Hawk was a patriot, fighting bravely in defense of his ancestral home; from the frontiersman’s point of view, he was only another “savage and bloodthirsty redskin” who had to be gotten rid of to make way for the “advance of civilization.”

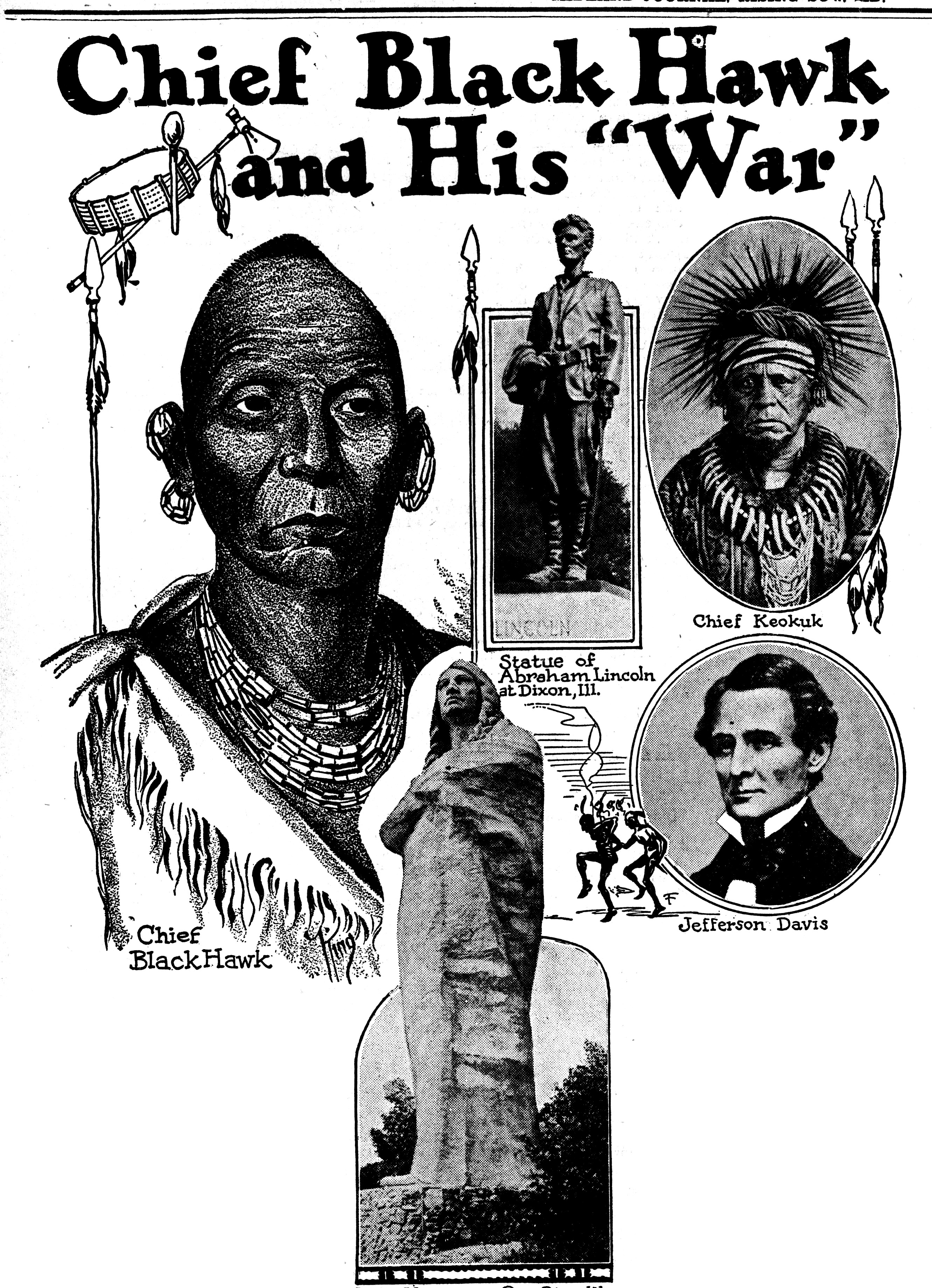

The leading figure in this now dimly-remembered war was Ma-ka-tai-me-slie-kia-kiak, or Black Hawk, a chief of the Sauk and Fox Indians, of whom Keokuk, or Watchful Fox, was the head chief. By the Treaty of November 3, 1804, made at N St. Louis, the Sauk and Fox agreed to surrender all of their lands east of the Mississippi. But it was not until the close of the War of 1812, when a wave of migration began to pour into Illinois, that the United States was ready to claim the land which it had acquired from the Indians. Keokuk and the majority of his tribe bowed to the inevitable and moved across the Mississippi to a new home in Iowa. But Black Hawk, who had been a disciple of Tecumseh, the great Shawnee, and an ally of the British in the War of 1812, let it be known that would not move to owa. He maintained that he had been deceived as to the terms of the St. Louis treaty and did not consider them binding upon him.

By 1831 so much friction between Black Hawk’s tribesmen and the Illinois settlers had developed that Governor Reynolds considered it advisable to call out the militia to “protect the lives and property” of the pioneers. But General Gaines, military commandant In the West, hoping to avoid the expense of a demonstration with force, summoned Black Hawk and his sub chiefs to a conference at Fort Armstrong on the Mississippi. The council was a stormy one and resulted in no satisfactory settlement of the difficulties, whereupon the militia on June 15 left their camp at Rushville, Ill. and marched upon Black Hawk’s village. They found it deserted and burned all the lodges. Then Gaines sent word to Black Hawk that the “hostiles” should come in for a peace talk and on June 30 Black Hawk and 27 of his followers signed a treaty with Governor Reynolds by which they agreed to refrain from hostile acts and to retire to lowa. There was no trouble with them until early in 1832 when Black Hawk crossed over into Illinois with some 2,000 Indians, of whom it was estimated more than 500 were warriors. Immediately the wildest rumors spread along the Illinois frontier. “Black Hawk and 1,000 blood-savages were descending upon the settlements to kill, scalp and burn.”

The Indian side of the story is rather different. Under the terms of the treaty which Black Hawk had signed with General Gaines the Indians were to be supplied with corn in place of that which they had left in their fields when they went to Iowa. What had happened is a familiar incident in the history of our relations with the Indians. The government failed to keep its promise. The amount of corn turned over to them was so meager that they began to suffer from hunger. In that emergency, a party of the Sauk, in the words of Black Hawk, crossed the river “to steal some corn from their own fields.”

Moving with his band up the Rock river, Black Hawk was overtaken by a messenger from General Atkinson, ordering him to return and recross the Mississippi. Black Hawk replied that he had not taken the warpath but was going on a friendly visit to the village of White Cloud, the Winnebago prophet, and continued his journey. Atkinson then sent imperative orders for him to return at once or he would pursue with his army and drive him back. To this the Indian leader protested that the general had no right to utter such a threat so long as his mission to the Winnebagoes was a peaceable one and that he intended to continue on his way.

Continue he did, until he was met by some Winnebago and Pottawatomie chiefs. In a council they made it plain that they had no intention of joining with Black Hawk in any war upon the Americans. Feeling that he had been betrayed by his Indian friends, the Sauk leader resolved to send a flag of truce to Atkinson, asking permission to descend the Rock river, recross the Mississippi and return to his reservation in lowa.

In the meantime Governor Reynolds had called out the militia and one of the captains of the hastily-organized companies, elected by his own men, was a lanky young storekeeper from New Salem named Abraham Lincoln. At about the time Black Hawk was holding his council with the other tribes, a large force of the militia had mobilized under General Whitesides near Dixon’s Ferry. At the request of Maj. Isaiah Stillman, Whitesides sent a scouting party of about 270 men under Stillman to try to locate the Indians. This party ascended the Rock river to the mouth of Sycamore creek and camped there, ignorant of the fact that they were only a short distance from Black Hawk’s camp.

Then occurred a tragic error—the first in a war filled with tragic blunders. Black Hawk sent three of his warriors under a flag of truce to ask for a conference. Stillman's undisciplined volunteers fired on them, killing one. Then followed the opera bouffe “battle” which has come down in history as “Stillman’s Run” in which 40 Indians sent 270 white men into headlong fight, inflicting a loss of about a dozen on the militia.

The news of this defeat spread even greater terror through the state. Governor Reynolds called out more troops and from Washington came the news that Gen. Winfield Scott had been ordered to the scene of the “war” with a thousand regulars. While en route to Illinois this army was attacked by the cholera and the mortality from that disease was greater than the total number killed and disabled by the Indians during the entire war.

The war dragged on throughout the summer of 1832 without any very decisive result, except that the superior forces of the whites gradually began to wear down the Indians. Finally the Indian leader suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of an army commanded by Gen. James D. Henry in a battle on the Wisconsin river, losing 68 warriors killed and many more wounded and disabled.

Black Hawk now realized that the game was up. With the remnants of his band he headed for the Mississippi, hoping to escape from the soldiers and find peace among his people already settled in lowa. He reached the Mississippi at the mouth of the Bad Axe river on August 1 with his starving warriors and his pitiful little band of women and children. Then occurred an incident which is often spoken of as a “naval engagement in an inland war.”

While Black Hawk and his tribesmen were trying to cross the river in canoes and on rafts, a steamer, the Warrior, hove into sight. On board was a detachment of soldiers and one small cannon. Black Hawk raised a white flag to ask for a parley. And again the flag of truce was dishonored by the white man. The captain of the Warrior asserted that he believed the flag was only a decoy used by the wily Indians to lure him into an ambush. So he ordered the cannon to be unlimbered and it began shelling the Indian camp. As a result 23 Indians were killed outright and many others were wounded.

The following day the pursuing troops under General Atkinson, which were joined by a detachment of regulars under Col. Zachary Taylor and an army of Wisconsin volunteers, came up and attacked Black Hawk’s camp. The end is not pleasant reading, for it was an Indian massacre —but contrary to the popular idea of that. It was a massacre of Indians by white men.

The weakened Indians were no match for the whites. Finding that their attempts to surrender were useless they resolved to sell their lives as dearly as possible. So they put up a desperate resistance but were driven at the point of the bayonet into the river. Indian women with children clinging to them plunged into the river only to be drowned or shot down by sharp shooters on the banks. The Warrior, returning from Prairie du Chien, added to the carnage by raking the shore with canister. More than 150 Indians were killed or drowned and only about 50 were taken prisoners.

Black Hawk and his chief warrior, Neapope, escaped to the north and sought refuge among the Wlnnebagoes. A short time later he surrendered to General Street at Prairie du Chien and was sent down the river to Jefferson Barracks, Mo., as a prisoner of war. The man placed in charge of him was a young lieutenant, the son-in-law of Colonel Taylor. His name was Jefferson Davis and of this man who later became President' of the Confederacy, Black Hawk said "He was a good and brave young chief with whose conduct I was much pleased, and he treated me with great kindness.”

After being Imprisoned in Fortress Monroe, Va., for a short time Black Hawk was allowed to return to the Sauk and Fox reservation in Iowa. There he died on October 3, 1838, and there he was buried in accordance with the customs of his people. So Black Hawk slept in peace at last but not in the soil which he loved so well —that of the beautiful Rock river country in northern Illinois. But his spirit broods over that land in the form of a giant concrete statue of an Indian, the work of Lorado Taft, which stands on a high bluff near Oregon, Ill., over-looking the Rock river. Although it is commonly referred to as “the Black Hawk statue,” the sculptor has repeatedly said that it is intended to symbolize the Indian—“a spirit unconquered while still the conquered race.” Even so, it may appropriately be a memorial to Black Hawk of the Sauk and Foxes, for his was such a spirit.

(© by Western Newspaper Union)

This article appeared in:

The Midland Journal, Rising Sun, Md., Friday April 8, 1932. (PDF)

The Parowan Times, Utah, Apirl 8, 1932.

The Millard County Chronicle, Utah, April 4, 1932.

The South Lyon Herald, Michigan, April 4, 1932.