CARROLL, Charles, of Carrollton, last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, b. in Annapolis, Md., 20 Sept., 1737; d. in Baltimore, 14 Nov., 1832. The sept of the O'Carrolls was one of the most ancient and powerful in Ireland. They were princes and lords of Ely from the 12th to the 16th century. They sprang from the kings of Munster, and intermarried with the great houses of Ormond and Desmond in Ireland, and Argyll in Scotland. Charles Carroll, grandfather of Carroll of Carrollton, was a clerk in the office of Lord Powis in the reign of James II., and emigrated to Maryland upon the accession of William and Mary in 1689. In 1691 he was appointed judge and register of the land-office, and agent and receiver for Lord Baltimore's rents. His son Charles was born in 1702, and died in 1782, leaving his son Charles, the signer, whose mother was Elizabeth Brook. Carroll of Carrollton, at the age of eight years, was sent to France to be educated under the care of the Society of Jesus, which had controlled the Roman Catholics of Maryland since its foundation. He remained six years in the Jesuit college at St. Omer's, one year in their college at Rheims, and two years in the college of Louis Le Grand. Thence: he went for a year to Bourges to study civil law, and from there he returned to college at Paris. In 1757 he entered the Middle Temple, London, for the study of the common law, and returned to Maryland in 1765. In June, 1768, he married Mary Darnall, daughter of Col. Henry Darnall, a young lady of beauty, fortune, and ancient family. Carroll found the public mind in a ferment over many fundamental principles of government and of civil liberty. In a province founded by Roman Catholics on the basis of religious toleration, the education of Catholics in their own schools had been prohibited by law, and Carroll himself had just returned from a foreign land, whither he had been driven by the intolerance of his home authorities to seek a liberal education. Not only were Roman Catholics under the ban of disfranchisement, but all persons of every faith and no faith were taxed to support the established church, which was the church of England.

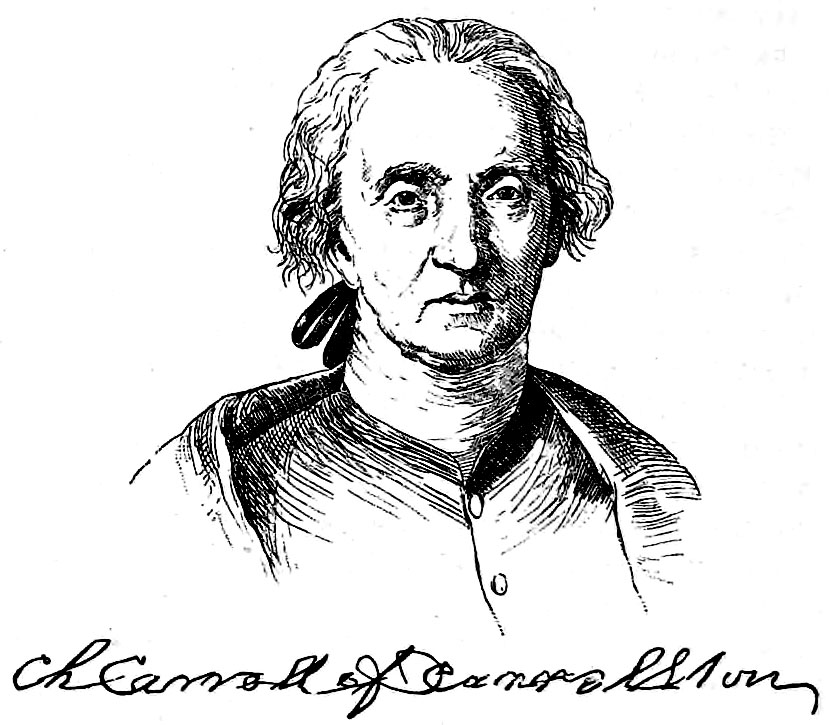

The discussion as to the right of taxation for the support of religion soon extended from the legislature to the public press. Carroll, over the signature “The First Citizen,” in a series of articles in the “Maryland Gazette,” attacked the validity of the law imposing the tax. The church establishment was defended by Daniel Dulany, leader of the colonial bar, whose ability and learning were so generally acknowledged that his opinions were quoted as authority on colonial law in Westminster hall, and are published to this day, as such, in the Maryland law reports. In this discussion Carroll acquitted himself with such ability that he received the thanks of public meetings all over the province, and at once became one of the “first citizens.” In December, 1774, he was appointed one of the committee of correspondence for the province, as one of the initial steps of the revolution in Maryland, and in 1775 was elected one of the council of safety. He was elected delegate to the revolutionary convention from Anne Arundel co., which met at Annapolis, 7 Dec., 1775. In January, 1776, he was appointed by the Continental congress one of the commissioners to go to Canada and induce those colonies to unite with the rest in resistance to Great Britain. On 4 July, 1776, he, with Matthew Tilghman, Thomas Johnson, William Paca, Samuel Chase, Thomas Stone, and Robert Alexander, was elected deputy from Maryland to the Continental congress. On 12 Jan., 1776, Maryland had instructed her deputies in congress not to consent to a declaration of independence without the knowledge and approbation of the convention. Mainly owing to the zealous efforts of Carroll and his subsequent colleagues, the Maryland convention, on 28 June, 1776, had rescinded this instruction, and unanimously directed its representatives in congress to unite in declaring “the united colonies free and independent states,” and on 6 July declared Maryland a free, sovereign, and independent state. Armed with this authority, Carroll took his seat in congress at Philadelphia, 18 July, 1776, and on 2 Aug., 1776, with the rest of the deputies of the thirteen states, signed the Declaration of Independence. It is said that he affixed the addition “of Carrollton” to his signature in order to distinguish him from his kinsman, Charles Carroll, barrister, and to assume the certain responsibility himself of his act. He was made a member of the board of war, and served in congress until 10 Nov., 1776. In December, 1776, he was chosen a member of the-first senate of Maryland, in 1777 again sent to congress, serving on the committee that visited Valley Forge to investigate complaints against Gen. Washington, and in 1788 elected the first senator from the state of Maryland under the constitution of the United States. He drew the short term of two years in the federal senate in 1791, and was again elected to the state senate, remaining there till 1801. In 1797 he was one of the commissioners to settle the boundary-line between Maryland and Virginia. On 23 April, 1827, he was elected one of the directors of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad company, and on 4 July, 1828, laid the foundation-stone of the beginning of that undertaking. His biographer, John H. B. Latrobe, writes to the senior editor of this Cyclopedia: “After I had finished my work I took it to Mr. Carroll, whom I knew very well indeed, and read it to him, as he was seated in an arm-chair in his own room in his son-in-law's house in Baltimore. He listened with marked attention and without a comment until I had ceased to read, when, after a pause, he said: ‘Why, Latrobe, you have made a much greater man of me than I ever thought I was; and yet really you have said nothing in what you have written that is not true’... In my mind's eye I see Mr. Carroll now—a small, attenuated old man, with a prominent nose and somewhat receding chin, small eyes that sparkled when he was interested in conversation. His head was small and his hair white, rather long and silky, while his face and forehead were seamed with wrinkles. But, old and feeble as he seemed to be, his manner and speech were those of a refined and courteous gentleman, and you saw at a glance whence came by inheritance the charm of manner that so eminently distinguished his son, Charles Carroll of Homewood, and his daughters, Mrs. Harper and Mrs. Caton.” The accompanying view represents his spacious mansion, known as Carrollton, still owned and occupied by his descendants.