On Pedestal of Fame

Statue of Daniel Webster Presented to the Nation

CAPITAL'S MAGNIFICENT TRIBUTE

President and Cabinet and Scores of high officials Gather and Listen to Praises of the Great New England Patriot by renowned Orators— Exercises at Lafayette Square Opera House Followed by Unveiling of Statue by Great Grandson.

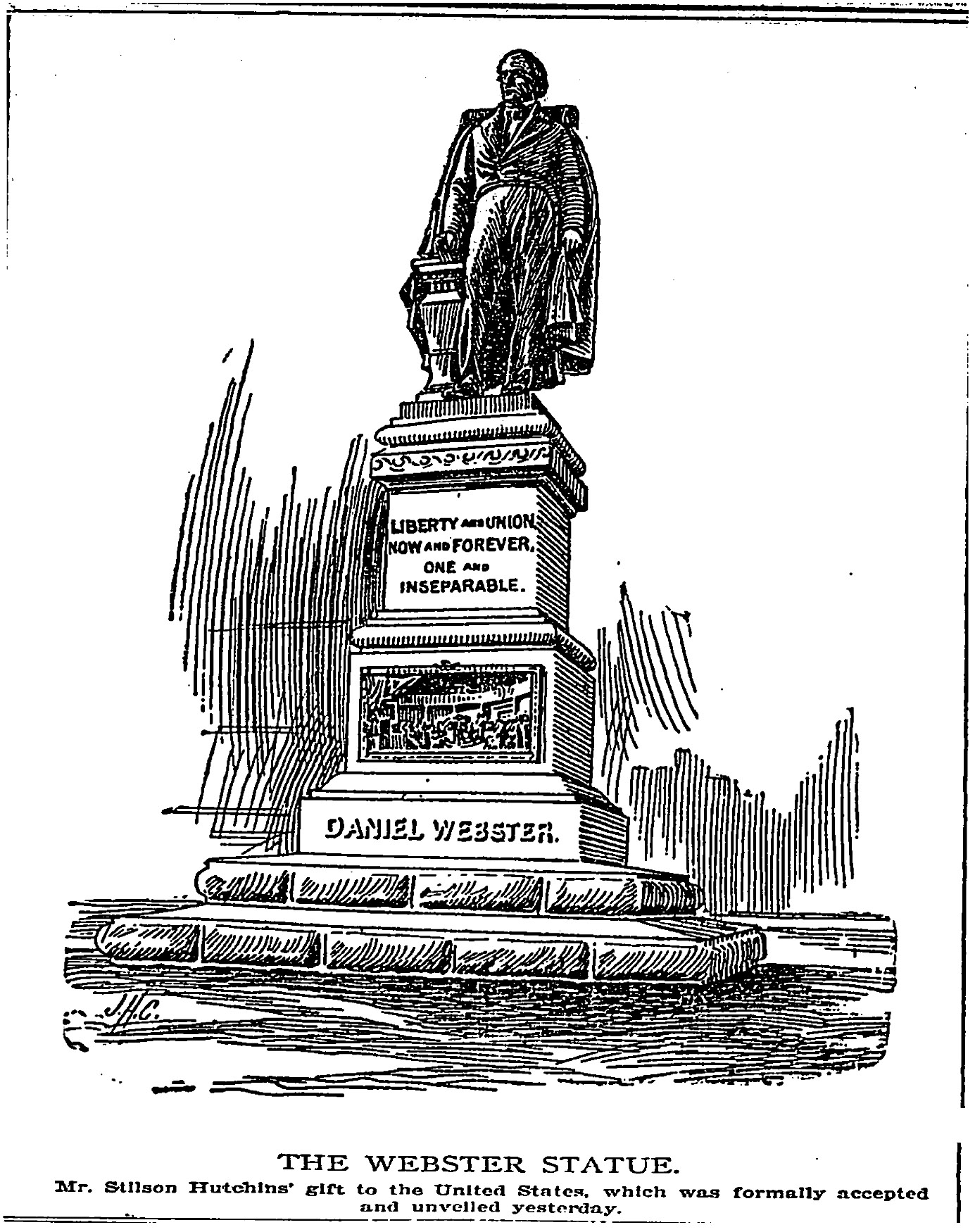

Standing on a pedestal as massive and rugged as New Hampshire's granite hills, the statue of Daniel Webster, modeled in bronze, of heroic size, was yesterday presented to the nation whose history he helped to make glorious. The great orator's attitude is defiant. He flings back a proud challenge well knowing that his name and fame are secure in the keeping of posterity. The sculptor has portrayed him as the lion that he was, and in the sturdy balance of the massive shoulders, the regal poise of the matchless head and the generous lines of the noble brow, there is enough to proclaim him king without the aid of scepter or diadem.

If any one had thought that there was he least uncertainty about Webster&apo;s place in the hearts of the people, those doubts were removed by the scenes of yesterday. An assemblage as distinguished as any which the orator addressed in life gathered to render homage to his memory. The President, accompanied by the members of the Cabinet, high officials both of the army and navy, statesmen from both branches of Congress, and a vast following of those in private life were present at the ceremonies of presentation and unveiling. The exercises where planned with singular appropriateness and impressiveness. The presiding officer was from New Hampshire, the state in which Webster was born. The orator of the day represents in the Senate the great Commonwealth which Webster served and which he valiantly defended in his reply to Hayne. The cord with unveiled the statue was pulled by Mr. Jerome Bonaparte, a great-grandson of the famous statesman. The donor of the memorial, Mr. Stilson Hutchins of this city, is a native of New Hampshire, and he knew Webster when a boy.

Stilson Hutchins

The Donor

A Distinguished Gathering.

The ceremonies of presentation took place at Lafayette square Opera House yesterday morning at 10 o'clock. Rarely has a more distinguished audience assembled there. Senator William E. Chandler, of New Hampshire, chairman of the committee on arrangements for Congress, presided, and delivered the opening address. Secretary Long, of the Navy, accepted the memorial in behalf of the United States, having been designated by the President to perform this duty. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, of Massachusetts, delivered the oration of the day.

President McKinley arrived early, and as he took his seat the Marine Band orchestra rendered “Hail to the Chief.” The President took a seat to the right of the center of the stage, directly opposite Senator Chandler. Behind the President were the members of the Cabinet, Secretaries Hay, Root, Hitchcock, and Postmaster General Smith, while Secretary Long occupied a seat a little further to the right. Among others on the stage were Chief Justice Fuller and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court, who were seated slightly in the rear of Senator Chandler. In a prominent place also were the members of the Congressional committee on arrangements, Senator Allison, of Iowa, and Senator Bacon, of Georgia, and Representatives Augustus O. Lovering, of Massachusetts; Robert G. Cousins, of Iowa; Frank G. Clarke, of New Hampshire; Amos J. Cummings, of New York, and John Wesley Gaines, of Tennessee.

An important guest was Gov. Crane, of Massachusetts, who, accompanied by several members of his staff, occupied seats near the center of the stage. Among others were Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles, H. Clay Evans, Commissioner of Pensions; Senators Hoar, Proctor, Tillman, Fairbanks, Frye, Clark, of Wyoming; Maj. McDowell, Clerk of the House of Representatives; Senator Platt, of Connecticut, and many others prominent in official life. Mr. Stilson Hutchins, donor of the statue, occupied a box.

Senator Chandler's Address.

As soon as the hum and noise incident to the arrival of the President has died away, Senator Chandler introduced Rev. Dr. Milburn, Chaplain of the Senate, who offered the invocation. At the close of the prayer Senator Chandler addressed the audience. After a few preliminary remarks, in which he paid a just tribute to the donor, he read the following letter from Mr. Hutchins presenting the statue to the nation:

Washington, Jan. 8, 1900

Hon. William E. Chandler, United States Senate,

Chairman of Special Committee of Congress, in Charge of Reception and Unveiling of the Statue of Daniel Webster:

Dear Sir: The bronze statue of Daniel Webster, which has been erected upon the site designated by the Joint Senate and House Committee, is appropriately inscribed and the work completed. I now desire, through you, to transfer to and vest in the United States full title to the statue, in the hope and belief that it will be found to be satisfactory both as a work of art and of portraiture. It gives me great satisfaction to be thus allowed to aid in some slight degree in perpetuating the name and fame of this great son of New Hampshire.

Very truly yours, Stilson Hutchins.

Senator Chandler then, referring to Webster's course regarding slavery, said:

“Other motives of minor force many have been present, but unquestionably his principal motive was devotion to these United States, which was, he thought, to be maintained by all reasonable sacrifices, and by every judicious compromise of conflicting opinions. He honestly believed that the measures of 1850 were reasonable and judicious, important, and necessary, as means for preventing the threatened dissolution of the Union. It must always be remembered that love for the Union had been the intense sentiment of Mr. Webster's whole lifetime. The great orations upon which his fame as an orator will ever live had been composed and uttered under the inspiration of this great love for the Union. He had been bold and outspoken against slavery when duty called him to conflict. He was sure in 1850 that the time had come for compromising with slavery to save the Union. It is easy, if we are determined to do so, to condemn the Union-savers of 1850, for the reason that all their compromising efforts for peace proved futile, and the Union was only saved by devastating war, with slavery destroyed in the progress of that war.

“But in all fairness and justice the integrity of their motives should nevertheless be conceded. They had grown up in the years first succeeding the formation of the National Constitution when its value was not fully appreciated by the people of the late colonies, and confederation and its ties were weaker that when at the end of more than a century of national growth under that Constitution we have become the richest country on the globe, and stand confessedly among the most powerful nations.

“Therefore, with no half-hearted or qualified praises but with unbounded admiration and unstinted affection, we ought to express on every suitable occasion our thankfulness for the gift of this country in the earlier days of it national life, of the sages and counselors, the orators and the statesmen, who, however diverse their views and actions may have been upon the great an burning question of slavery, yet on the whole, wisely and patriotically inspired the hearts and guided the footsteps of the free people of the new republic. Among all these founders of the nation whom we so gratefully remember and so profoundly respect and honor, who was the superior, who was equal to Daniel Webster?”

Accepted by Secretary Long.

Secretary Long was then introduced, and he accepted Mr. Hutchins' gift in behalf of the nation in the following words:

To George Washington and his associates, who in 1787 framed the Federal Constitution, we owe that great paper. It bound the thirteen independent colonies into a union and created the United States of America. In it they gave us the ample letter and frame of government.

To the overwhelming arguments, nearly fifty years later of Daniel Webster in the Senate, and the luminous judgements of John Marshall on the bench, we owe its development by interpretations and construction into the great charter of powers which now constitute the national authority. They illuminated its letter and national spirit. They breathed into its frame the full life of national sovereignty. In the momentous debate in which at that time they participated over the measure of its grants of power —a debate of giants— the issue was between a limitation on the one hand, which would have narrowed the growth of the young republic and endangered the integrity of the Union, an on the other and expansion which insured the indestructability of the Union and let free the republic to its largest development. As they prevailed, so they made the United States indissoluble by internal convulsion and equal to the emergencies of the future which confronted them, or which confront us.

The statue of one of them, the great jurist in serene dignity of high office, already adorns the front of the Capitol. To-day on Massachusetts avenue —name dear to him as his to her— with his face to the Capitol and to the chief justice, you unveil the statue of the other, the great expounder of the Constitution and defender of the Union, and the foremost lawyer, orator, and statesman, whose words imbedded in the common political literature of his countrymen, come to the tongue, as come those of no other, like familiar passages from the poets and the Psalms.

I am deputed by the President to speak his acceptance of it for the United States with the highest appreciation of the man it commemorates, in acknowledgement of the gift this added to the reproductions in enduring bronze of those to whom she said “Well done.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge then made the commemorative address. He was frequently interrupted by applause as he paid his tribute to the great statesman whose name was thus being honored. His effort was on a par with others which have already made him famous as a scholar and an orator. He said in part:

Senator Lodge's Eloquence.

“We can thank the artist who has conceived, and most unreservedly can we thank the generous and public-spirited citizen of New Hampshire who has given the statue which we unveil this morning. If anyone among our statesmen has a title to a statue in Washington, it is Daniel Webster, for this is the National Capital, and no man was ever more national in his conceptions and his achievements than he.

Born in New Hampshire, he represented Massachusetts in the Congress of the United States, and thus two historic Commonwealths cherish his memory. But much as he loved them both, his public service was given to the nation, and so given that no man doubts his title to a statue here in this city. Why is there neither doubt nor question as to Webster's right to this great and lasting honor, half a century after his death? If we cannot answer this question so plainly that he who runs may read, then we unveil our own ignorance when unveil his statue and the act without excuse. I shall try, briefly, to put the answer to this essential question into words. We all feel in our hearts and minds the reply that should be made. It has fallen to me to give expression to that feeling.

Reared to His Greatness.

“We do not raise a monument to Webster upon debatable grounds and thus make it the silent champion of one side of a dead controversy. We do not set up his statue because he changed his early opinions upon the tariff, because he remained in Tyler's Cabinet after that President's quarrel with the Whigs, or because he made upon the 7th of March a speech about which men have differed always and probably will differ. Still less do we place here his graven image in memory of his failings or his shortcomings. History, with her cool hands, will put all these things into her scales and mete out her measure with calm, unflinching eyes. But this is history's task, not ours, and we raise this statue on other grounds.

“To his greatness, then, we rear this monument. In what does that greatness, acknowledged by all, unquestioned and undenied by any one, consist? Is it in the fact that he held high office? He was as brilliant member of Congress, for nineteen years a great Senator, twice Secretary of State. But ‘the peerage solicited him, not he the peerage.‘ Tenure of office is nothing, no matter how high the place. A name recorded in the list of holders of high office is little better that one writ in water if the office-holding be all. We do not raise this statue to the Member of Congress, to the Senator of the United States or to the Secretary of State, but to Daniel Webster. That which concerns us is what he did with these great places which were given to him; for to him, as to all others, they were mere opportunities. What did he do with these large opportunities? Still more, what did he do with the splendid faculties which nature gave him? In the answer lies the greatness which lifts him out of the ranks and warrants statues to his memory.

Webster's Imposing Appearance.

“Strong, massive, and handsome, he stood before his fellow-men looking upon them with wonderful eyes, if we may judge from all that those who saw him tell us.

“So imposing was he that when he rose to speak, even on the most unimportant occasion, he looked, as Parion says, ‘like Jupiter in a yellow waistcoat,’ and even if he uttered nothing but commonplaces, or if he merely sat still, such was his ‘might and majesty’ that all who listened felt that every phrase was charged deep and solemn meaning, and all who gazed at him were awed and impressed. Add to all this a voice of great compass, with deep organ tones, and we have an assemblage of physical gifts concentrated in this one man which would have sufficed to have made even common abilities seem splendid.

“When Webster stood one summer morning on the ramparts of Quebec an heard the sound of drums and saw the English troops on parade, the thought of England&apo;s vast world empire came strongly to his mind. The thought was very natural under the circumstances, not at all remarkable nor in the least original. Some years later, in a speech in the Senate, he puts his thought into words, and this, as every one knows, is the way he did it:

A power which has dotted over the surface of the whole globe with her possessions and military posts, whose morning drumbeat, following the sun and keeping company with the hours, encircles the earth with one continuous and unbroken strain of the martial airs of England.

“the Sentence has followed the drumbeat round the world and has been repeated in England and in the antipodes by men who never heard of Webster, and probably did not know that this splendid description of the British empire was due to an American. It is not the thought which has carried these words so far though time and space. It is the beauty of the imagery and the magic of style. Let me take one more very simple example of the quality which distinguishes Webster&apo;s speeches above those of others, which makes his words and serious thoughts live on when others, equally weighty and serious, perhaps, sleep or die. In his first Bunker Hill oration he apostrophized the monument, just as any one else might have tried to do, and this is what he said:

Let it rise, let it rise till it meet the sun in his coming: let the earliest light of morning gild it, and parting day linger and play on its summit.

“Here the thought is nothing, the style everything. No one can repeat those words and be deaf to their music or insensible to the rhythm and beauty of the prose with the Saxon words relieved just sufficiently by the Latin derivatives. The ease with which it is done may be due to training, but the ability to do it comes from natural gifts.

Put Thoughts Into Words.

“It is not to be supposed for an instant that Webster discovered the fact that the Constitution had made a nation, or that he first and alone proclaimed a new creed to an unthinking generation. His service was equally great, but widely different from this. The great mass of the American people felt dumbly, dimly perhaps, but none the less deeply and surely, that they had made a nation some day to be a great nation, and they meant to remain such and not sink into divided and petty republics. This profound feeling of the popular heart Webster not only represented but put into words. No slight service this capacity to change thought into speech, to five expression to the feelings and hopes of a people and crystallize them forever in words fit for such use.

“In politics Jefferson embodied in the Declaration of Independence the feelings of the American people and sounded to the world the first note in the great march of Democracy, which then began. The Marseillaise in words and music burned with the spirit of the French revolution and inspired the armies which swept over Europe. Thus Webster gave form and expression, at once noble and moving, to the national sentiment of his people. In what he said men saw clearly what they themselves thought, but which they could not express. That sentiment grew and strengthened with every hour, when men had only to repeat his words in order to proclaim the creed in which they believed, and after he was dead Webster was heard again in the deep roar of the Union guns from Sumter to Appomattox. His message, delivered alone as he could deliver it, was potent in inspiring American people to the terrible sacrifices by which they saved the nation when he slept silent in the Union and the Constitution because they meant national greatness and national life, was the dominant conviction of Webster's life.

Passionate Love of Country.

“It was not merely that as a statesman he saw the misery and degradation which would come from the breaking of the Union as well as the progressive disintegration which was sure to follow, but the very thought of it came home to him with the sharpness of a personal grief which was most agonizing. When in the 7th of March speech, he cried out ‘What States are to secede? What is to remain American? What am I to be?’ A political opponent said the tone on the last question made him shudder as if some dire calamity was at hand. The greatness of the United States filled his mind. He had not the length of days accorded to Lord Bathurst, but the angel of dreams had unrolled to him the future and the vision was ever before his eyes.

“This passionate love of his county, this dream of his future, inspired his greatest efforts, were even the chief cause at the end of his life of his readiness to make sacrifices of principle which would only have helped forward what he dreaded most but which he believed would save that for which he cared more deeply. In a period when great forces were at work which in the inevitable conflict threatened the existence of the Union of States, Webster stands out above all others as the champion, as the very embodiment of the national life and the national faith. More than any other man of that time he called forth the sentiment more powerful that all reasonings which saved the nation. It was a great work, greatly done, with all the resources of a powerful intellect and with an eloquence rarely hard among men. We may put aside all his other achievements, all his other claims to remembrance and inscribe alone upon the base of his statue the words uttered in the Senate ‘Liberty and Union, now and forever, on and inseparable.“ That single sentence recalls all the noble speeches which breathed only greatness of the country and the prophetic vision which looked with undazzled gaze into a still greater future. No other words are wanted for a man who so represented and so expressed the faith and hopes of a nation. His statue needs no other explanation so long as the nation he served and the Union he loved stall last.”

The Statue Unveiled.

At the conclusion of Senator Lodge's address the official members of the audience, including the President and members of the Congressional committee, drove in carriages to Scott Circle, where the ceremony of unveiling was to take place. A large crowd had assembled around the statue in spite of the drizzling rain, which fell about noon. A platform had been erected for the Marine Band, which furnished music for the occasion, under the direction of Lieut. Santelman. Mr. Jerome Bonaparte then joined the party, and the strains of “America“ were struck up by the band, this great-grandson of Daniel Webster pulled the cord which released the shroud of flags from round the statue of his ancestor.

The large number of spectators then crowded up to view the work of art. The President and public officials spoke admiringly of the figure and pronounced it to be a striking likeness of the great New Englander. The statue was the center of attention among pedestrians and travelers in the vicinity of Scott Circle throughout the whole day.

Description of the Statue.

The bronze statue of Webster is a distinct addition to the already notable collection of tributes to heroes and statesmen which now adorn public parks of the city and Statuary Hall, at the Capitol. Heroic in size, fully thirty feet from the base of the pedestal to the head of the figure, it commands the immediate attention of all who pass near it. It is situated on the southwestern part of Scott Circle, and the statue faces south on Sixteenth street, toward the White House.

Gaetano Trentanove

The Sculptor

The sculptor, Chevalier Gaetano Trentanove, conceived the figure in his most artistic vein, and it will add largely to his renown as an artist, a renown already secure on account of the superb statue of Pere Marquette, now in Statuary Hall. Signor Trentanove studied the costumes and habits of the period very closely. He looked at many old portraits, not only of Webster, but of other statesmen of his day. In his bas reliefs on the panels he has reproduced scenes with almost photographic accuracy, and with an artistic spirit which makes the numerous characters seem alive.

Early in 1897 Mr. Hutchins commissioned Signor Trentanove to execute the statue. The artist set about to obtain all the likenesses available of the great orator. It was cast in bronze at Florence and brought to this country last year. Upon its arrival in America a resolution was introduced in the Senate by Senator Gallinger, of New Hampshire, providing for the erection of the statue in the city. An appropriation of $4,000 was then voted by Congress for the construction of a pedestal upon which to place the statue.

Like the Webster He Knew.

The figure of Webster is in bronze, twelve feet high. The great orator is portrayed in his most characteristic pose, his features sternly set, and the attitude as of a speaker pausing before some weighty utterance. The shoulders are thrown back in a defiant manner, as if in answer to a challenge. In the right hand is a book of reference, resting on a stand. A cloak of the style of the day is gracefully suspended from the shoulder, while the left hand hangs free. Mr. Hutchins himself has seen Webster, and admires him as one of the greatest characters in American history. He can truly say that the sculptor has caught the conception of the Webster of his memory.

The pedestal is eighteen feet high, of red granite, highly polished. The base is impressively constructed, and is in itself a work of art. It is relieved on opposite sides by panels of bronze representing some of the greatest scenes in national life, and certainly the greatest in the career of the orator. The most striking is that which portrays Webster replying to Hayne in the old Senate Chamber, now the Supreme Court room. About 100 figures ae in bas relief, and they all stand out distinctly. There is John C. Calhoun, presiding; Senator Hayne, of South Carolina, and greatest of all, Webster, delivering his matchless burst of oratory. Surrounding the panel in a beautiful design are Webster's immoral words, “Liberty and Union. Now and Forever.” In the frame of the panel art and industry are displayed in a powerful manner.

On the other side is another panel, representing Webster delivering the other great effort of his life, his oration at the dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument. The orator is represented as giving one of his burning utterances, and the great crowd is cheering and applauding. In each of the panels Webster's figure stands out in bold relief, showing that the greatest attention has been paid to the details.

The presentations of a worthy statue of Webster to the nation has long been a cherished dream of Mr. Hutchins. He always regarded the likeness in Statuary Hall at the Capitol as inadequate, so far as expressing the characteristics of his idol. He regarded it as too feeble, and he has not hesitated to designate it as “dyspeptic.” He considered that the tremendous power and virility of the great New Englander was lacking. He aided the artist in securing the best likenesses of Webster, and it is probably due to his efforts and the boyish memory he retained that the statue is so true to life.

Career of the Donor.

Stilson Hutchins, the donor of the statue, is a native of New Hampshire and a great admirer of the character of Webster. He was born at Whitefield, Coos County in that State, on November 14, 1838, and his ancestors have been associated with great events in American history from the landing of the Mayflower to the battle of Bunker Hill. Mr. Hutchins was educated in Cambridge, Mass., and began newspaper work in Boston at the age of seventeen. In 1856 he went with his parents to Iowa, where he started a country newspaper. His vigor and force as a political writer attracted the attention of party leaders, and he was called upon to take charge of the leading Democratic organs of the State, first in Des Moines, and later in Dubuque. At the latter city he became owner of the Herald. At the close of the war he went to St. Louis, and in spite of limited capital and fierce competition, in six years he succeeded in making his property, the Times, a paying newspaper. He afterwards came to Washington. He founded the Washington Post in December, 1877. Mr. Hutchins continued in the management of the Post until January, 1889. In 1889 Mr. Hutchins presented to the National Capital a statue of Benjamin Franklin, wrought out of Carrara marble by Ernst Plassman, which has been erected on the triangular plot at the intersection of Pennsylvania avenue and Tenth street. Along in the '80s Mr. Hutchins became greatly interested in the Mergenthaler Linotype Machine, and it was in a measure due to his capital and financiering that the invention was made a success. Mr. Hutchins has been prominently associated with the large business interests of Washington ever since his residence in the city. He constructed the Great Falls Electric Railroad which was recently sold to and absorbed by the Washington Traction and Electric Company.

On Pedestal of Fame, The Washington Post, January 19, 1900, Page 3.