Governors of Maryland From the Revolution to the Year 1908, by Heinrich Ewald Buchholz, 1908.

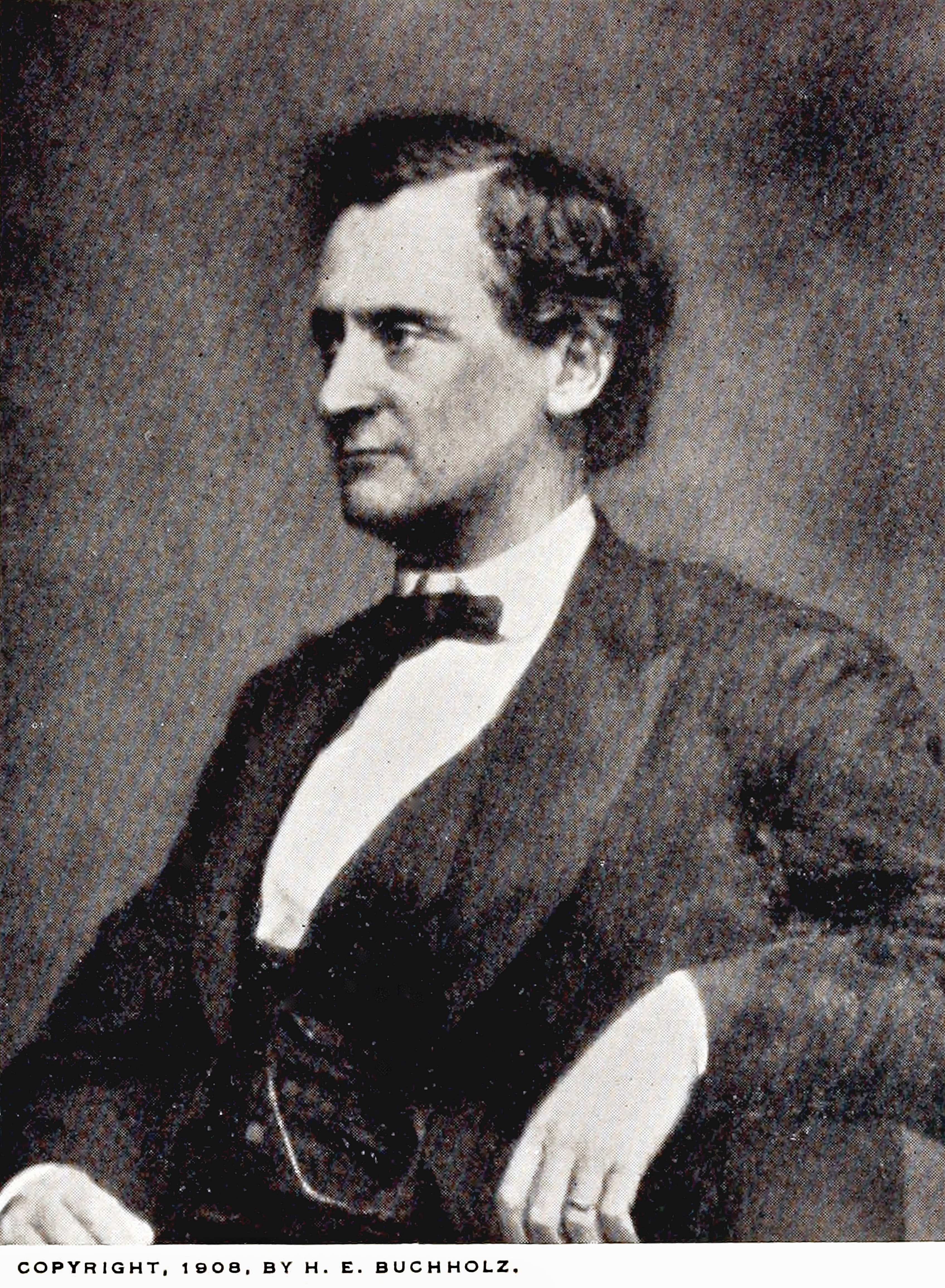

Enoch Louis Lowe

XXIX

On the morn of the Civil War, when Maryland was torn asunder by the divided sentiment of her people, a native poet wrote a patriotic hymn which has since become almost a classic. His heart was with the southland; his plea was for the cause of the so-called cotton states; and his purpose was to stir the passion of Marylanders so that they would rally to the support of the Confederacy. In the song with which James R. Randall sought to rouse the people of Maryland he dwelt upon the glory of the state's particular heroes; and no more convincing proof of the esteem in which Governor Lowe was then held by his fellow-statesmen can be found, than that his name was one of those used by the poet in order to stir the people's hearts:

Come! 'tis the red dawn of the day,

Maryland! My Maryland!

Come! with thy panoplied array,

Maryland! My Maryland!

With Ringgold's spirit for the fray,

With Watson's blood at Monterey,

With fearless Lowe and dashing May,

Maryland! My Maryland!

In the story of Maryland's part in the war several men who had earlier served as governor occupy positions of importance. Some of these former state executives were with the south; at least one was in sympathy with the north; but none excelled, and it is doubtful if any equalled Mr. Lowe in devotion to the cause which each espoused.

Mr. Grason, the first popularly elected governor, was an ardent supporter of slavery and a friend of the south. His successor, Francis Thomas, was one of the bitterest opponents of the Confederacy. The next two governors —Thomas G. Pratt and Philip Francis Thomas— were sentimentally inclined toward the southern cause and, although neither took part in the conflict, each gave to the Confederate army the service of a son. Mr. Lowe, the last governor under the constitution of 1776, went further than any of his immediate predecessors. When the war began, he took his way to the southland, and there gave moral and material support to the Confederacy. If secession was rebellion, then he was one of the most violent rebels who came out of Maryland; and the final defeat of the southern cause brought a sorrow to his heart which never thereafter left it.

Enoch Louis Lowe, born August 10, 1820, was the son of Lieutenant Bradley S. A. and Adelaide (Vincendiere) Lowe; Lieutenant Lowe was a graduate of West Point Academy. The early years of the governor were passed at the beautiful family estate, The Hermitage, a tract of 1000 acres in Frederick county upon the Monocacy river. He attended St. John's School in Frederick City, and later, at the age of thirteen, was sent abroad to complete his studies. He was entered at Clongowas Wood College, near Dublin, and subsequently studied at the Roman Catholic College of Stonyhurst, where he continued for three years.

After completing his academic studies, 1839, Mr. Lowe made an extensive tour of Europe, and upon his return to America traveled about the states for a year before returning home to take up seriously the work of life. He then became a student of law under Judge Lynch, of Frederick, and in 1842, at the age of twenty-one was admitted to the bar.

Although Mr. Lowe formed a law partnership with John W. Baughman at Frederick, and gave much thought to building up for himself a reputation in his chosen profession, he did not for long keep a single eye to the law, but early evinced a desire for a part in the political affairs of his section. In 1845 he appeared as a candidate on the Democratic ticket for the state legislature, and his campaign resulted in two things —his election to the House of Delegates and the winning of more than a little reputation as an able stump speaker.

Mr. Lowe became prominent as an advocate for constitutional reform in Maryland and through this advocacy his fame had spread so far by 1850 that, when the Democratic state convention met in that year, he was chosen upon a “reform” platform as the standard-bearer of his party. The Whigs nominated for Governor William B. Clarke, of Washington County, and the two aspirants for the gubernatorial chair had several public debates during the campaign.

Mr. Lowe's personal popularity in Baltimore won for him the election. His majority throughout the state was just 1492 votes, but Baltimore —which gave a Whig candidate for mayor a majority of 777 votes— gave Mr. Lowe, the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, a majority of 2759.

Mr. Lowe was but twenty-nine years old when nominated for governor, although he satisfied the constitutional requirement by arriving at the age of thirty before election, much was made of his youth, and upon one occasion a would-be detractor interrupted him while he was making a speech by asking: “How old are you?” but the Democratic candidate flashed back the magnificent reply: “a wife and four children.” He had been married, May 29, 1844, to Miss Esther Winder Polk, daughter of Colonel James Polk, of Princess Anne. Mrs. Lowe bore her husband eleven children, seven of whom with the mother survived the governor.

Governor Lowe was inaugurated January 6, 1851, and continued in office until January 11, 1854. His administration, therefore, witnessed the change in the state-government from the old constitution of 1776 to the constitution of 1851. At a special election in May, 1850, the people of Maryland had declared for a constitutional convention, and at an election held in the following September delegates to this convention were chosen. The body thus elected was only slightly whiggish in complexion, and the document it devised —during its session from November 4, 1850, to May 13, 1851— was largely made up of compromises between the two opposing elements. The greatest gain for the people was that the constitution of 1776, burdened with amendment upon amendment, was superseded by a governmental document that at least expressed clearly the things that it treated. Before the proposed constitution could be fully digested by the people, it was placed before them for ratification, and was given a small majority at a special election on June 4, 1851.

During Governor Lowe's administration the state fully recovered from the financial depression that had resulted some years earlier in the advocacy of repudiation of public debts. Governor Thomas, who preceded Mr. Lowe, had warned the people against reducing the amount of taxation, and declared that such a reduction, despite the cheerful outlook, would be a dangerous step. But Governor Lowe boldly advised the very thing against which Mr. Thomas had warned, and in 1853 the people of Maryland were required to pay but 15 cents on the $100, whereas in the several years prior thereto the annual tax rate for the state had been 25 cents. Another notable feature of the Lowe administration was the completion of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to the Ohio river, which, according to the original plans of the promoters, was to have been the western terminus of the line.

During the administration of Mr. Lowe, General Kossuth, the Hungarian patriot, visited America and was the guest of Maryland's chief magistrate for several days. Although Mr. Lowe was heartily in sympathy with the foreigner and the cause he represented, he was unable to accord either any aid from the state government. Mr. Lowe was named as minister extraordinary and plenipotentiary to China by President Pierce, but declined the post.

After the close of his administration Mr. Lowe assumed a much more prominent rôle in national politics than he had taken before his governorship. He became one of the great figures among those who took up the cause of the south, not for office nor for personal advantage, but solely because of a love for the land and the people south of the Mason and Dixon Line. He helped to win for Buchanan the democratic nomination for president in 1856, and was active in the campaign which resulted in Buchanan's election. Mr. Lowe was active in the presidential campaign of 1860, supporting John C. Breckinridge even more heartily than he had supported Buchanan.

When the war began, Mr. Lowe remained in Baltimore long enough to serve the south to the fullest extent of his ability in his native state. He was a man without fear, and what he did, he did openly. While others tried to evade answering the question as to their allegiance, Governor Lowe stood up fearlessly for the cause of the south. Later he went to Virginia, where he became the guest of honor of the legislature of the Old Dominion. His address delivered before the legislature was regarded by that body as of sufficient moment to warrant its publication and distribution by the state.

Governor Lowe wanted Maryland to secede, and he believed that the state would ultimately join the Confederacy. “God knows,” he declared, “Marylanders love the sunny south as dearly as any son of the Palmetto State. They idolize the chivalric honor, the stern and refined idea of free government, the social dignity and conservatism which characterize the southern mind and heart, as enthusiastically as those of their southern brethren who were born where the snows never fall.&rdqou; He was bitter in his denunciations of Mr. Hicks who “had purposely left her (Maryland) in a defenseless condition, in order that he might without peril to himself deliver her up at the suitable time to be crucified and receive his thirty pieces of silver as the price of his unspeakable treachery.”

Mr. Lowe spent the greater part of his voluntary exile in the south in Augusta and in Milledgeville, Georgia. After the war Governor Lowe returned to Maryland, where he lived from November, 1865, until May, 1866, when he moved with his family to New York. It was not only the ironclad oath —which his self-respect would not permit him to take— that sent Mr. Lowe out of his native state; but Baltimore at that time did not seem to offer him the means of supporting his large family by his professional work in the way that he was accustomed to providing for it. He had lost heavily through the war, and in Brooklyn, where he was to take up his residence, he saw a large enough field for practice to insure him a considerable income. His leaving Baltimore with his family to go to a strange city is but another evidence of the wonderful courage of the man.

For some time after removing to New York, Mr. Lowe was in much demand as a lecturer. He was several times solicited to enter the political circles of the Empire state. Except for his brief activity in the Hancock-Garfield campaign, however, he remained in comparative retirement. He was for a while counsel of the Erie Railroad Company, but upon the death of James Fiske this relationship was dissolved.

A newspaper correspondent, writing from Brooklyn at the time of Governor Lowe's death, asserted that he had “lived a very retired life, and outside of the immediate circle of his family friends was hardly ever seen or heard of. It was often regretted here that Mr. Lowe did not take the public place his abilities and career warranted, but he seemed to care only for the peace and quiet of his family and home, and thus occupied himself out of the sight and bustle of the busy world.” Governor Lowe died on August 23, 1892, at St. Mary's Hospital, where he had undergone an operation which proved unsuccessful. His body was removed to Frederick, and was privately interred on August 25. Governor Lowe having requested that no funeral sermon be preached at his burial.

XXIX, Enoch Louis Lowe, Governors of Maryland From the Revolution to the Year 1908, by Heinrich Ewald Buchholz, 1908, Page 158.

An earlier version of the is article appeared in The Baltimore Sun:

XXIX—Enoch Louis Lowe, Governors of Maryland: a Series of Biographies, by Heinrich Ewald Buchholz, The Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1907.