Name of Statue on Capitol Dome Was Subject of Extended Controversy

Jefferson Davis Changed Original Design

Writer Gives ‘Freedom’ as Correct Title of Art Work Modeled by Thomas Crawford

by John Clagett Proctor

The United States Capitol in 1858, showing the incompleted dome.

The old Washington City Canal is shown in the foreground.

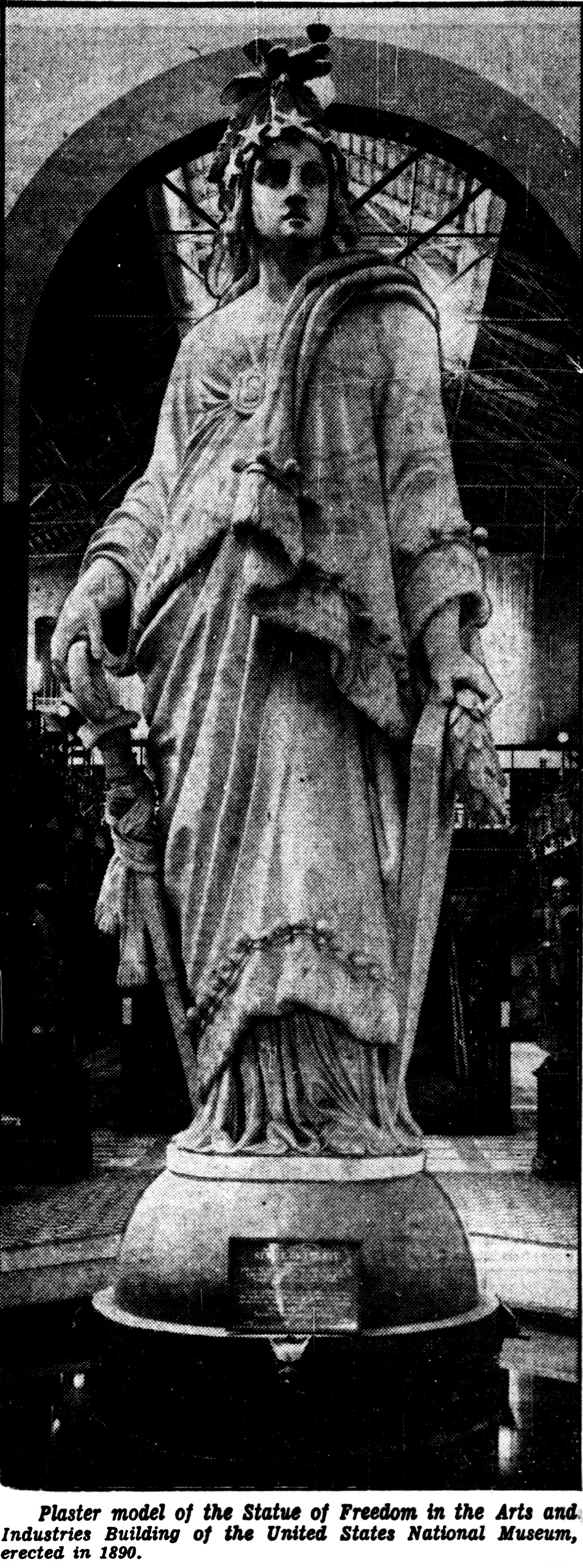

One of the uncertainties which seem to exist in the minds of the citizens of Washington and the public generally is the correct title or name of the statue that surmounts the dome of the United States Capitol Building. And, also, because of the great distance of this figure from the ground, few seem to know whether it represents a man, a woman, a mythological person, an American Indian or just what, and very little, indeed, is known about its general design, though nearly all of this information could be obtained by a visit to the arts and industries building of the United States National Museum, where in the rotunda of this interesting structure is exhibited the original plaster model of this celebrated statue.

Of course, this is not the only statue around Washington over which there is a difference of opinion as to name, but it is surely the most notable one over which there is any doubt. The sculptor of this colossal bronze figure, Thomas Crawford, was born in New York, in 1814, though he went to Rome in 1835 to study art and spent much of his subsequent life in Italy. He designed many works of art prior to executing the model for the statue that stands on the dome of the Capitol, but even this is not all the art he has contributed toward beautifying that magnificent building, the corner stone of which was laid by President Washington September 18, 1793.

Jefferson Davis' Part.

Of Crawford's celebrated statue there are many interesting stories, one of which relates to the part taken in its designing by Jefferson Davis, who, as Secretary of War, was required by law to give his approval to the model, which was submitted to him by way of photographs, since the work was done abroad. At this time, in 1856, Montgomery Meigs was a captain in the Engineer Corps, U. S. A., and detailed to construction work then being carried on at the Capitol, and it was through him that the photographs were forwarded to Mr. Davis and the exceptions taken by the secretary of War are contained in his reply dated January 15, 1856, in which he says:

“Sir: The second photograph of the statue with which it is proposed to crown the dome of the Capitol impresses me most favorably. Its general grace and power, striking first view, have grown on me as I studied its details.

“As to the cap, I can only say, without intending to press the objection formerly made, that it seems to me that its history renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free, and would not be enslaved.

“The language of art, like all living tongues, is subject to change; thus the bundle of rods, if no longer employed to suggest the functions of the Roman lictor, may lose the symbolic character derived therefrom, and be confined to the rough signification drawn from its other source, the fable teaching the instructive lesson that in union there strength. But the liberty cap has an established origin in its use as the badge of the freed slave, and though it should have another emblematic meaning today, a recurrence to that origin may give to it in the future the same popular acceptation which it had in the past.

“Why should not armed liberty wear a helmet? Her conflict being over, her cause triumphant, as shown by the other emblems of the statue, the visor would be up, so as to permit, as in the photograph, the display of a circle of stars expressive of endless existence and of heavenly birth.

“With these remarks I leave the matter to the judgment of Mr. Crawford; and I need hardly say to you, who know my very high appreciation of him, that I certainly would not venture, on any question of art, to array my opinion against his.

“Very respectfully, your obedient

servant,

“JEFFERSON DAVIS,

“Secretary of War.”

Crawford's Decision.

To the suggestions made by Mr. Davis, Mr. Crawford apparently acquiesced, for on March 18, 1856, he writes:

“I read with much pleasure the letter of the honorable Secretary, and his remarks have induced me to dispense with the ‘cap’ and put in its place a helmet, the crest of which is composed of an eagle's head and a bold arrangement of feathers, suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes.”

This is practically the full extent of the influence exercised by Mr. Davis over the Statue of Freedom which was placed in position December 2, 1863, and which is likely to remain until it falls down, for few, indeed, would agree to see it removed or remodeled at this late day. Whatever else may be said of it, it cannot be denied that it is an American creation, and that, of course, is what counts with the people of this great Republic.

However, there was a suggestion to remodel this statue as recently as 1924, when a story appeared in The Star carrying these caustic words: “I have no hesitation in stating that we have no goddess of liberty on the great dome. I believe we should employ an expert with a cold chisel and cut that pagan helmet off the head of the statue and place instead a liberty cap with a tiara of 48 stars of the States—something to symbolize liberty, unity and America.”

The bringing to this country a hundred years ago of the Greenough statue of Washington demonstrated the difficulties of shipping to the States from abroad works of art of any considerable size or weight, or both. And the bringing over of the model of the Statue of Freedom at a later date truly was an exciting and eventful journey, as told by Charles E. Fairman in his “Art and Artists of the Capitol of the United States of America.” Says Mr. Fairman:

“The bark containing the plaster model of the Statue of Freedom sailed from Leghorn, Italy, April 19, 1858, bound for New York. On the 22d, having sprung a leak which continued with more or less force until the 19th of May, It was decided to put into Gibraltar to make the necessary repairs before proceeding farther on the voyage. Upon arrival, the cargo, excepting the model, was landed and stored, and the vessel was calked. Upon the completion of the repairs, the vessel sailed thence on the 26th day of June for the port of destination, New York.

“Having encountered much stormy weather, with heavy gales from the northwest, from the date of leaving Gibraltar, the vessel was found on the 1st of July to be leaking badly. The leak gradually increased until the 12th, when, finding the vessel to be making water at the rate of 12 inches per hour, it was resolved to lighten her by throwing over board a part of the cargo. One hundred and seventeen bales of rags and 48 cases of citron were jettisoned. On the following day 133 bales of rags were thrown overboard. Finally, on the 27th of July, the leak having increased to 16 inches per hour, it was determined for safety to put into Bermuda, at which port they arrived on the 29th of July. Upon surveys held, the vessel was condemned and sold. The cargo, which had been landed and stored, was finally forwarded to destination by a vessel which had been chartered and sent to Bermuda for that purpose.”

Plaster model of the Statue of Freedom

in the Arts and Industries Building of the United States National Museum,

erected in 1890.

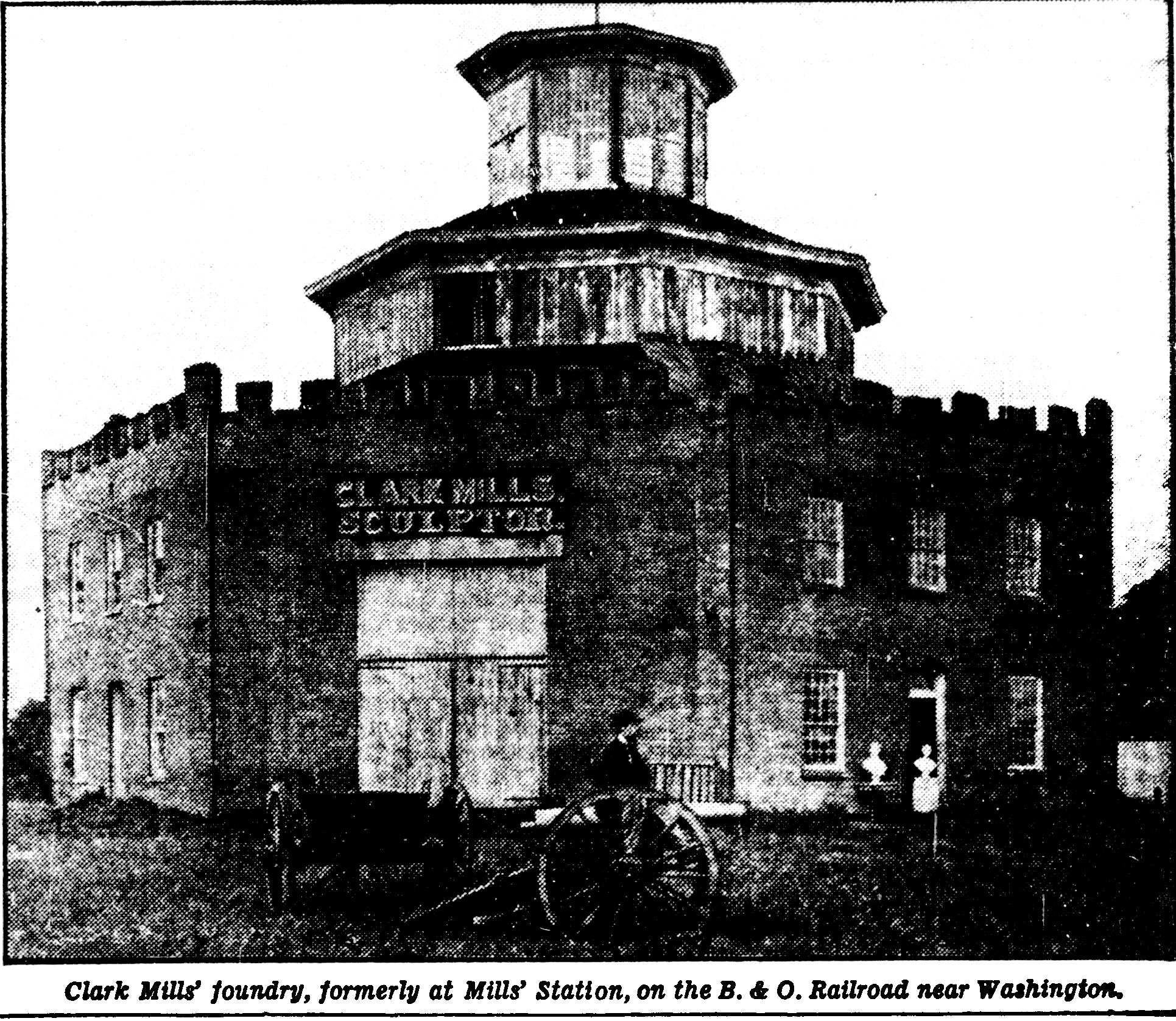

Crawford, the sculptor of this statue, died in 1857, the year before it was shipped from Italy to this country, and subsequently a contract was let to Clark Mills for casting it in bronze in his foundry, which formerly stood at Mills' Station on the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

Clark Mills' foundry, formerly at Mills' Station, on the B. & O. Railroad near Washington.

For his work in casting the figure Mills was paid $9,800, and for labor, iron work and copper, a further amount of $10,996.82 was expended. For the model, Crawford was paid $3,000, making the total for the statue, as we see it today, $23,796.82.

Erecting the Statue of Freedom was quite an engineering feat, and though there are several accounts of what took place during the course of its erection, and when the head was finally placed in position, an account printed in The Star of October 6, 1883, is worthy of consideration:

“Charles F. Thomas, the mechanical engineer, who placed the Statue of Freedom on the Capitol in Washington,” the item goes on to say, lives with his family in a cottage at 32 Eleventh street, Brooklyn. He is of stalwart proportions. A long gray beard gives him a venerable appearance, but his keen eyes are restless and sparkle when he talks.

“You see that framed certificate on the wall?” he said. “Well, that was signed by Abraham Lincoln 20 years ago, a month before he was assassinated. It testified that Mr. Thomas, superintendent of construction of the new dome, placed the Statue of Freedom on the dome on December 2,1853, at 12 m., and that the scaffolding whereby the tholus was built and the statue was raised to its position and designed and erected by him.

“I was eight years building the dome and placing the statue in position. You see under the glass bell on the table yonder a model of the top of the new dome, the statue, and the circular scaffolding, whose top is above the head of the statue. That little model, a few inches high, and whose largest timbers are no bigger than matches, will sustain a weight of 100 pounds. The elevation of the top of the scaffolding on the western face of the Capitol was 390 feet. Two workmen and my self only were allowed to go on the structure. We climbed to the top by means of cleats fastened to one of the uprights. Washington is a windy place. Gusts used to come from the most unexpected quarters on that lofty place.

“The head of the statue was hoisted to its position by means of an eyebolt in the cluster of feathers in the helmet of the statue. The instant it settled into place. 34 guns were fired by a park of artillery east of the Capitol, and the guns of all the forts near Washington responded.

“It was by the wish of Jefferson Davis that the head of the statue was crowned with the helmet, surrounded by a circlet of stars and topped off with an irregular but picturesque bunch of feathers. Mr. Davis was Secretary of War in 1855. The sculptor, Crawford, designed a Statue of Freedom with the Liberty cap. To the cap Mr. Davis objected, because, he said, the cap was worn by freed slaves among the ancient Greeks. Mr. Davis objected that the design suggested that Americans had been slaves. Mr. Crawford objected to a change. Nevertheless he prepared a design similar to that now on the Capitol. Mr. Davis approved it, and it was adopted. At once newspapers opposed to Mr. Davis in politics said that his motive in securing the change in the design was that he did not want an emblem on the Capitol which indicated that slaves could ever be made free.

“After the scaffolding was partly removed I stood on the feathers of the helmet while a photgorapher took my picture. He couldn't say! ‘Look pleasant,’ or ‘Hold your chin a little higher, please,’ because he was at South First street and New Jersey avenue. I tied a rope through the eyebolt in the center of the top of the head so that a bight was formed, which hung down the sloping side of the head. I placed my right foot in the bight. The left foot was on the top of the head. Standing thus, the photograph was taken.

“In the stereoscopic view which Mr. Thomas has his form looks like that of a blackbird newly lighted on Liberty's head.

“After the photographer had dropped his handkerchief to signify that he had done with me, I dropped on my right knee and took a hammer from one pocket and some steel dies of letters from another pocket. With a blow on each die,I stamped words on the topmost feather of the plume. They have never been seen by any one but myself, and will not be in a thousand years. I believe the statue will never need repairs. The words are as follows:

“A. Lincoln, President of the United States: Hugh Walker, Architect; B. B. French, Commissioner of Public Buildings; Charles F. Thomas, Superintendent of Construction of the New Dome.”

“Is it a fact that Vulcan's face in the allegorical painting to the eye of the dome, over the rotunda, is your portrait?”

“It is a fact.”

It has been questioned whether or not the plaster model in the National Museum and the bronze statue surmounting the Capitol are in appearance identical. In speaking of the plaster model, when it was transferred to the museum in 1890, the late Edward Clark, architect of the United States Capitol, said:

“* * * It formerly stood in the Old Hall of the Representatives, but was taken apart and stored in the basement of the building. * * *” when it arrived at the museum, it had been taken apart, and was in a number of sections—perhaps as many as eight, although—the bronze figure is said to only contain five sections bolted together. It is quite likely—and about the only conclusion one could come to—that these plaster sections were used in making the sand molds from which was cast the bronze statue, and naturally, would necessarily be identical, except, of course, as to material of composition.

Parts Put Together.

At the museum, the parts were put together by the late Lt T. Dig Bolles, U. S. N., and Theodore Mills, son of the same Clark Mills who carried out Crawford's design in metal. Bolles did the engineering work and Mills modeled in the missing parts—for it was not by any means in perfect condition after having been stored in the basement of the Capitol for so many years. Feathers were broken off a star or two was missing, several of the balls circling the border of the cloak or dress were absent, a part of the nose was gone, as well as other projecting parts easily broken in moving. To a sculptor these were easily replaced, as they were of a decidedly minor character, and the restoring of them did not alter in the least the appearance of the model to that of the bronze cast.

After the plaster model of the statue was erected and restored in the rotunda of the museum, in 1880, it was labeled “Statue of Liberty.” And soon thereafter appeared a communication “To the Editor of The Evening Star,” reading as follows:

“Some weeks ago The Star published a list (extracted, I believe, from the annual report of the architect of the Capitol) of the works of art within the Capitol and in the custody of the architect. Among them was enumerated a plaster copy in miniature of the statue of the ‘Goddess of Freedom’ which surmounts the dome. In your issue of Monday you published a letter from Mr. J. P. Walker in regard to the same statue, which he calls ‘the grand statue of liberty on the dome of the Capitol.’ Your editor who puts the headings to the published articles places over Mr. Walker's letter the caption ‘The Goddess of Liberty.’ Now, the statue on the dome is not that of the ‘Goddess of Freedom’ or the ‘Goddess of Liberty,’ nor yet that of ‘Liberty.’ The name given to it by its author, the sculptor Crawford, was Freedom, pure and simple. Freedom and liberty are nearly synonymous terms, and Mr. Walker is not so very far wrong. But the architect of the Capitol and The Star ought to be better informed on a matter of this kind. It seems to me that the plain designation, ‘Freedom,’ is so dignified and so appropriate to this noble work of art that it should be adhered to. T. F. J.”

The result was that after carefully weighing the evidence the label was changed to “Freedom,” and so it is today, and the “Statue of Freedom” is also the form used in the Congressional Directory, giving a brief history of the Capitol.

Name of Statue on Capitol Dome Was Subject of Extended Controversy by John Clagett Proctor, The Washington Star, March 02, 1941, Page C-4. (PDF)