Crawford and Mills Sculptors

By Elmo Scott Watson

© Western Newspaper Union, 1933.

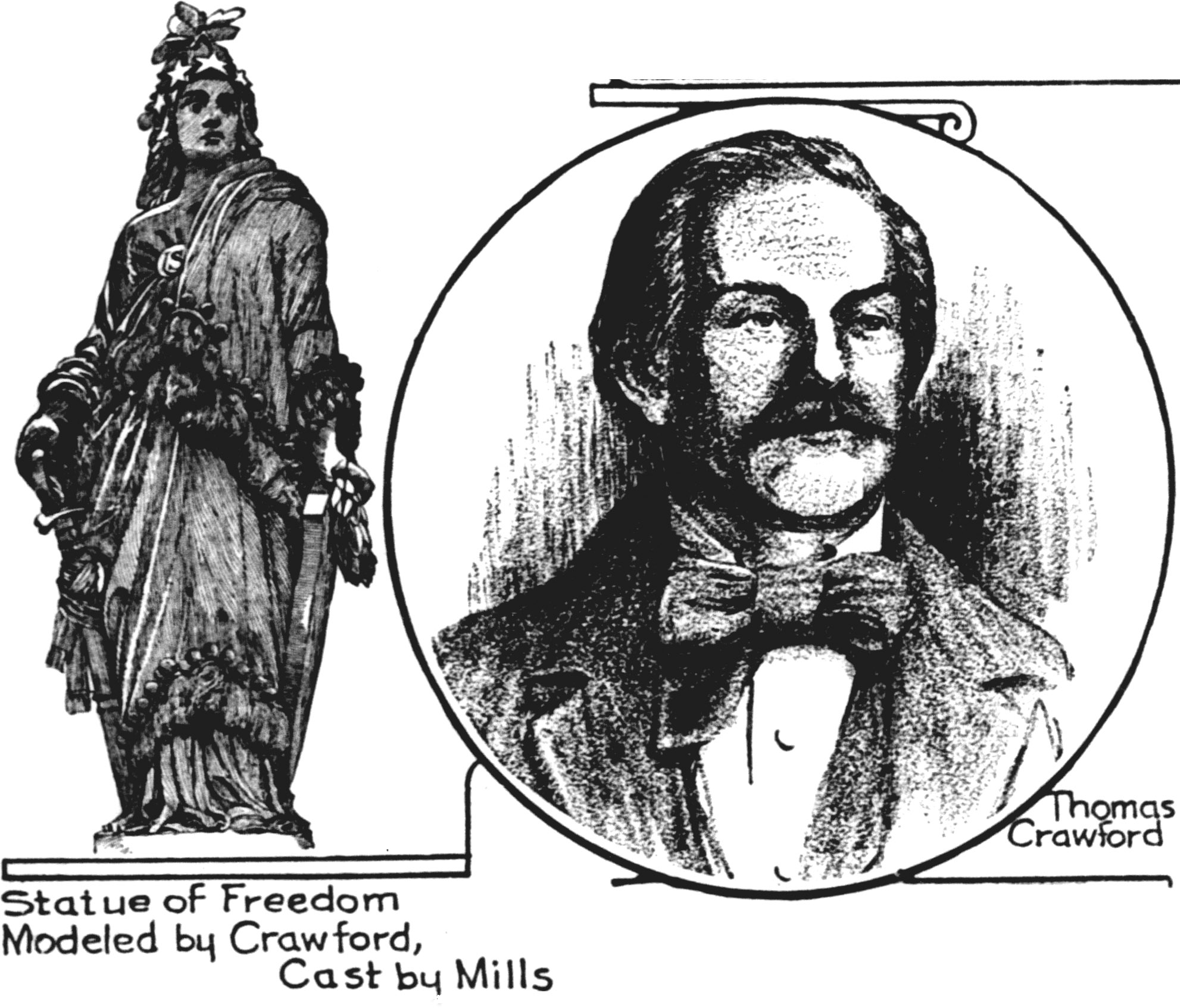

They call her “The First Lady of Washington,” and they don't mean the wife of the President of the United States. They say she is “Washington's best known girl,” and they don't mean some reigning belle in Capital society. They speak of her as “Uncle Sam's Wife,” but that isn't possible because “Uncle Sam” is only a personification, a fiction created by the imagination, while she is a tangible, visible figure. She is variously (and erroneously) known as the “Goddess of Freedom,” the “Goddess of Liberty” and the “Indian Goddess.” But her real name is the statue of Freedom and for 70 years she has stood atop the dome of the Capitol in Washington.

The statue of Freedom is the product of the efforts of two sculptors, famous in their day but now almost forgotten by a generation of Americans who know the names of Lorado Taft, Gutzon Borglum and Jo Davidson better than they do those of Clark Mills and Thomas Crawford.

Insofar as this article has most to do with Mills and Crawford, let us consider their careers and their claims to distinction before expanding the theme of the statue of Freedom.

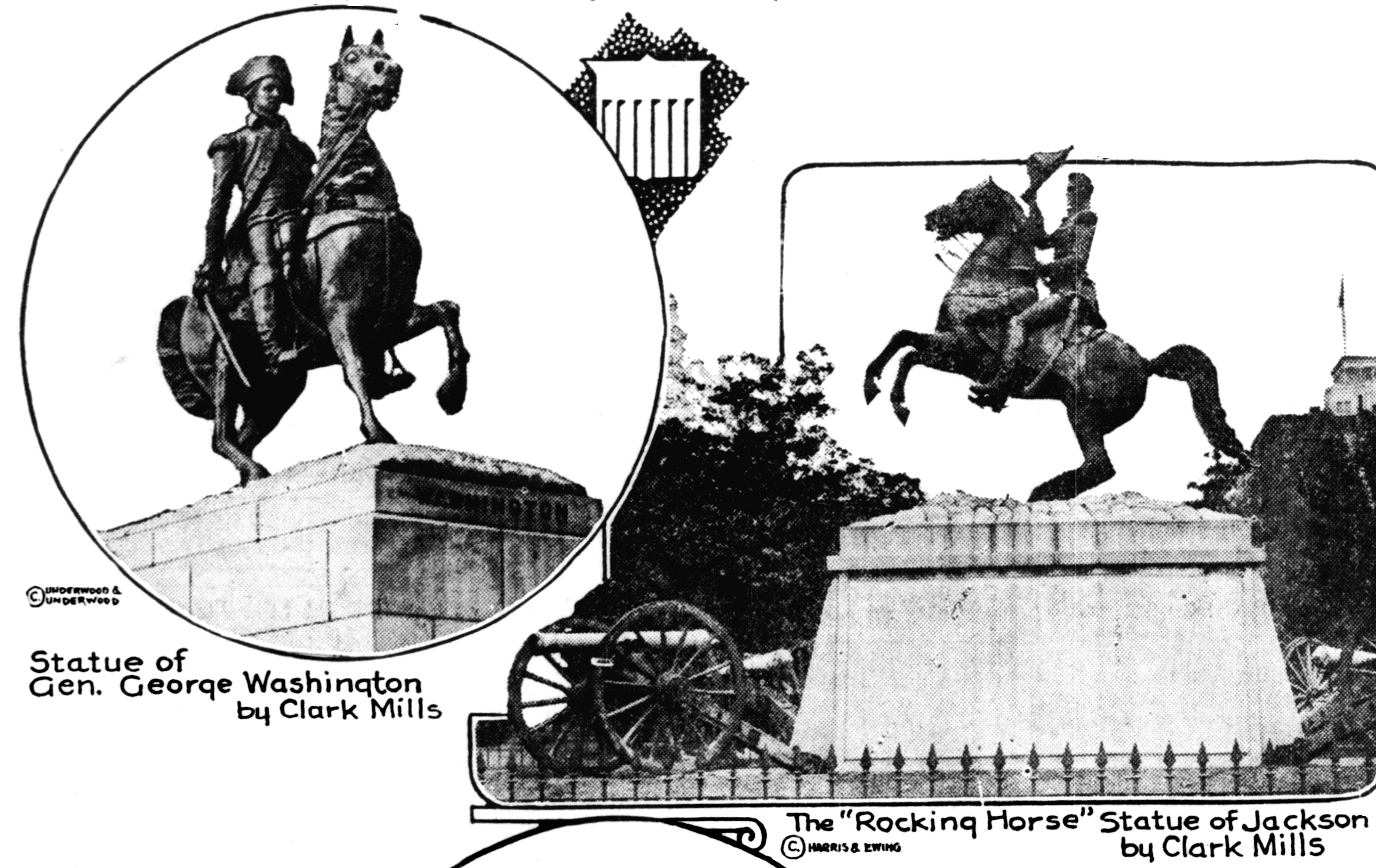

Mills' fame rests chiefly upon his being the sculptor of the first equestrian statue erected in this country, the famous “rocking horse statue” of Andrew Jackson In Lafayette park, near the White House, In Washington; his having also executed the equestrian statue of Washington, depicting him at the Battle of Princeton, which stands at Twenty-third street and Pennsylvania avenue; his part in giving to the nation the statue of Freedom on top of the Capitol; and the fact that he was a sculptor whose only lessons were those he gave himself.

Mills was born In Onondaga county, New York, December 1, 1815. His parents died when he was five years old and the youngster went to his uncle's home to live. Even as a child he was restless and unhappy. At thirteen he ran away, doing odd Jobs here and there as he traveled farther and farther from Onondaga county. He worked on farms; he cut cedar posts in swamps; he learned to mill.

He reached Charleston, S. C., after a great deal of traveling and there he settled. There, too, he learned a new trade that appealed to him— stuccoing. At the age of twenty he had little schooling and less training in art and sculpturing. His education was the study of human nature that he had gathered during his travels and a keen interest in faces. It was while working with stucco that he wondered why a cast could not be made from living face. This would assure realism and would be inexpensive. He experimented on his friends and the results were so good that he soon had a number of orders.

This local success stirred young Mills. He must try to cut a bust in marble. Night after night he worked out his new Idea, carving the features of John O. Calhoun. When he completed his work he brought it to the city council and waited, laughing at himself for thinking that his untutored hands and mind would produce anything great. In 1835 the council of Charleston awarded a gold medal to his bust of Calhoun and appropriated money to purchase it. With the money thus earned Mills planned to go to Europe to study his art, but a friend advised him to go first to Washington and view the statuary in the Capitol.

His visit to Washington became an important event of his life. He was introduced to Cave Johnson, then postmaster general and president of the Jackson monument committee, who asked him to submit a design for a bronze equestrian statue of General Jackson and who assured him that “the committee would furnish the bronze,” which they later did in a curious historical way.

Not having seen Jackson or an equestrian statue of any kind, Mills hesitated, in doubt of his own abilities, but his Yankee enterprise came to his rescue. He produced a design which was acceptable to the committee and after nine months of disheartening labor, he finally brought to the committee a miniature model of rather startling originality.

The hind legs of the horse were brought exactly under the center of the body, while his front legs pawed the air, imparting both a sense of marvelous balance and motion. Two years were required to finish the plaster model and another year elapsed before the committee came forward with the bronze. They got the stock by appropriating all the old cannon captured by General Jackson at the battle of New Orleans, which were broken up and melted. After many failures in balancing the horse in bronze, the statue was finally finished.

On the thirty-eighth anniversary of the battle of New Orleans. In 1853, the statue was unveiled in the presence of a vast crowd and Clark Mills himself. Stephen A. Douglas, master of ceremonies, made an eloquent address and called on Mills to speak. But Mills had never been an orator, and his first public success awed and frightened him. He faced the audience and opened his mouth, but words would not come. Silently he pointed to the veiled statue and at his gesture, instead of the awaited spoken word, the veil was withdrawn. Andrew Jackson, seated on his mount, stood before his people. There was silence, then prolonged applause.

For Mills that occasion meant nationwide fame. He was asked to cast a statue of Washington at the battle of Princeton for the Capital. He did, using guns donated by congress.

Mills spent the last years of his life making busts of prominent citizens. He was not a publicity seeker during his life, and after his death in 1883, at the age of sixty-eight, his fame lessened. Today he is virtually forgotten by that group, notorious for short memory—the Public.

But if Mills could not win enduring fame by his own efforts as a sculptor, he does have some reflected glory from another sculptor for his part in giving to the nation the statue of Freedom which looks down upon the country which she is supposed to symbolize from her lofty pedestal in the Capital of that country. That other sculptor was Thomas Crawford, also a native of New York where he was born March 22, 1814. After studying in New York he went to Italy in 1834 for further study and he remained in Europe for 15 years. Returning to this country in 1849 he was commissioned by the state of Virginia to execute an equestrian statue of Washington for the city of Richmond.

At about this time plans were going forward for the completion of the Capitol building and President Pierce placed it in charge of Jefferson Davis, who was secretary of war in his cabinet. Davis supervised the extensions and commissioned Crawford, then residing in Italy, to execute the colossal statue which was to surmount the dome.

In March, 1856, Crawford forwarded to Secretary Davis photographs of the model of the statue as originally designed by him. The figure of Liberty in the photographs represented a female crowned with a laurel wreath, bearing in her hand a huge olive branch. The war secretary objected to the wreath, and the sculptor suggested that a liberty cap be substituted. To this Davis even more strenuously objected “because it was the historical emblem of a freed slave and ought not to be there,” the slavery question being then at its most crucial stage. As finally approved by Davis, the model of the statue bore a coronal of nine stars. The statue originally had represented Armed Liberty, but after the minor changes it was decided to call it the statue of Freedom.

On April 1, 1857, Crawford wrote to Davis asking permission to have the statue cast in bronze under his personal supervision at the Royal Bavarian foundry in Munich, then the most famous foundry in the world. But Crawford was destined never to see his work completed for he died five months later In London, on September 10, 1857.

The price for the model had been set at $5,000 and after Crawford's death his wife undertook to complete his contracts. On April 19, 1858, the plaster model of the statue of Freedom was loaded on the bark Emily at Leghorn, Italy, and started its voyage to the United States. Three days from port the vessel sprung a leak.

At Bermuda the vessel was condemned and the precious statuary for the United States Capitol was stored on the island for several months. The sections of the model were shipped to America piecemeal on various boats, and the last of the statuary finally arrived In Washington about a year after it had started accross the stormy Atlantic from Italy.

Almost six years now elapsed since the commission for the statue had been given, four years had passed since the design had been executed, and many more years were fated to pass before the figure was finally cast into bronze and placed into position. By this time the rumblings of the approaching Civil War were growing louder and work on the Capitol was suspended.

Upon the delivery of the different sections of the plaster model of the statue in Washington, an adroit Italian who worked about the Capitol assembled them so skillfully that no crevices were perceptible at the joints, the bolts were all firmly riveted inside and their location deftly concealed by the plaster covering. Then the model was put on a wooden pedestal and set up for exhibition purposes in the old chamber of the house of representatives, the present Statuary hall.

After remaining there for two years, the model was removed to the Crypt, the room under the rotunda of the Capitol which was originally designed for the tomb of George Washington. Many years later the model was moved to the Smithsonian Institution and there it may be seen today.

In 1860 the plans for casting the statue in bronze got under way. And it was at this point that Clark Mills came into the picture. He owned a foundry on the Bladensburg road three miles from Washington and he was given the contract for casting the statue. But now another obstacle arose. The Italian workman who had assembled the sections of the model was directed to take it apart for the molds. This he flatly refused to do unless lie received a large bonus and a long-time contract of employment, stating that he alone knew the key of its construction and to attempt to separate the sections without this knowledge would mean the destruction of the model.

The situation seemed desperate. But Mills recalled that he owned a highly intelligent mulatto slave named Philip Reed, who had long been employed about the foundry as an expert and was an extremely skillful workman. Reed made a critical examination of the figure and at length announced that he could solve the mystery and dismember the plaster model without damaging it. He first inserted a pulley into an iron eye affixed to the head of the model, then gently strained the rope until joint after joint became visible. The inside bolts were then discovered, scraped of plaster and carefully removed.

The model was again reduced to sections and sent to the Mills foundry for casting. Soon after the casting began the Civil war opened and all such work was ordered suspended. But, deaf to the thunder of the guns of war, Mills persisted in his work until he had produced a perfect bronze cast of the statue. This was some time in 1861 or 1862. The statue was taken to the southeast corner of the Capitol grounds, where it remained for many months.

Precisely at 12 o'clock noon on December 2, 1863, the colossal figure was hoisted by the steam apparatus that had been employed in the construction of the dome and in 20 minutes it had reached its lofty pedestal in safety. As soon it was properly adjusted the American flag unfurled over its head.

The statue is the most striking symbol in the whole country of the principle upon which this nation was founded. It is also an enduring memorial to two sculptors whose names are all but forgotten but should be remembered by their fellow-Americans—Clark Mills and Thomas Crawford.

Crawford and Mills Sculptors by Elmo Scott Watson, © Western Newspaper Union, 1933.

This article appeared in an number of papers in 1933, including:

Carbon County News, Red Lodge Montana, October 25, 1933, Page 7.

The Western News, Libby Montana. October 26, 1933, Page 7.

The Coolidge Examiner, Coolidge, Arizona, October 27, 1933, Page 4. (PDF)

(See also the Arizona State Library.)