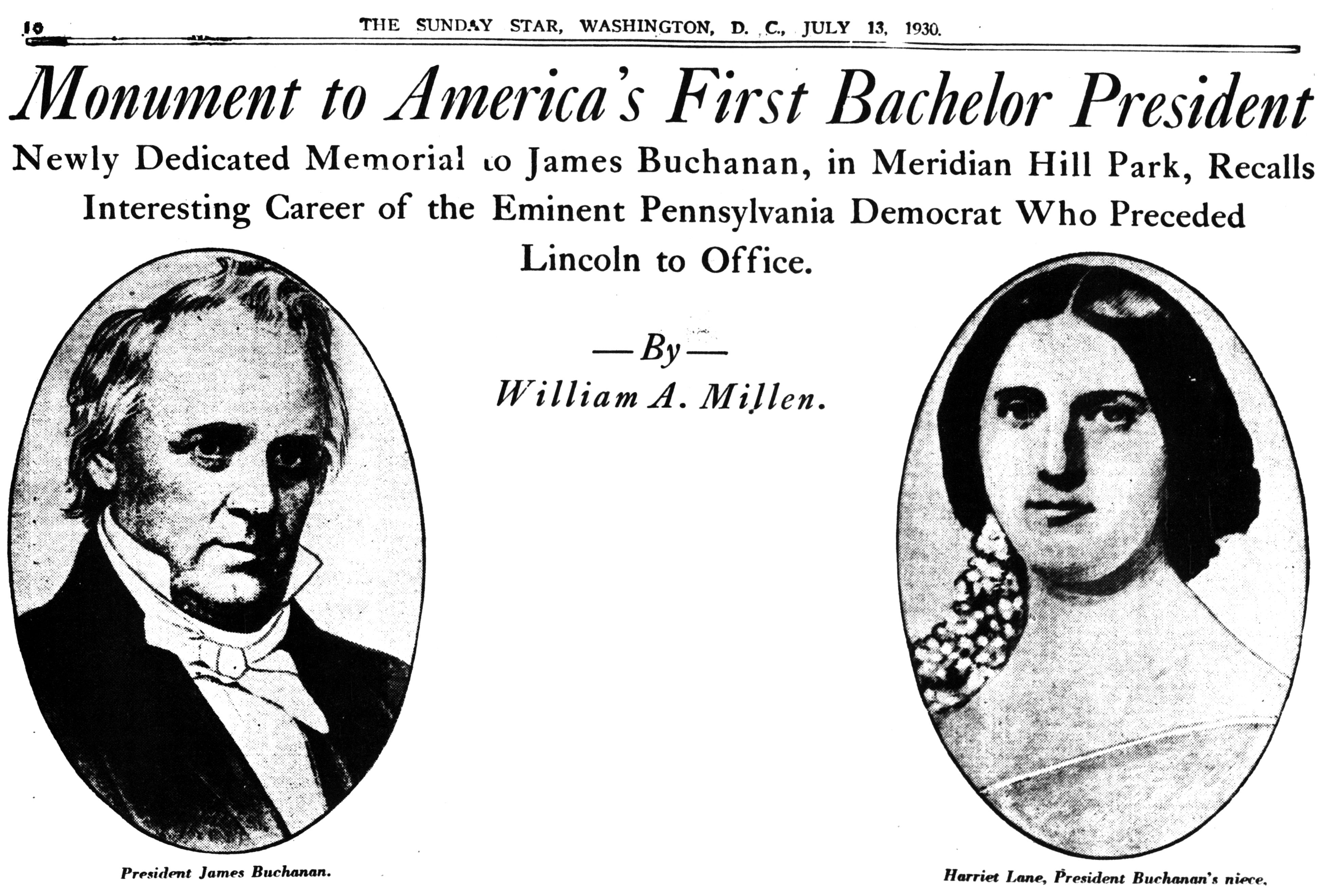

Monument to America's First Bachelor President

Newly Dedicated Memorial to James Buchanan, in Meridian Hill Park, Recalls Interesting Career of the Eminent Pennsylvania Democrat Who Preceded Lincoln to Office.

by William A. Millen.

BEHIND the unveiling of Washington's newest memorial, raised up to the honor of President James Buchanan, lies an entrancing story of how Washington almost lost this monument by a few days and how a beautiful and gracious niece, who acted as his First Lady of the Land, sought to enshrine his name in a beautiful sculptural offering that would outlive the wrath of his enemies.

The newly dedicated monument that pays tribute to Buchanan in Meridian Hill Park is the apex of a story that had its beginnings more than half a century ago. Buchanan was America's first bachelor President. To fill the role of mistress of the White House, when he came here in 1857, when the clouds of the Civil War were already on the troubled horizon, Buchanan chose his beautiful niece, Harriet Lane. And now the Washington that has well-nigh forgotten the bitter strife engendered by his occupancy of the White House and the storm that was to beat its full force at Bull Run, at Gettysburg and at Shiloh gazes complacently upon the memorial to Buchanan, made possible by the money of the pretty niece who rode with him to his inaugural in that March of 1857.

Newspaper and other accounts of the time assert that the Buchanan inaugural was a brilliant one. The man that Buchanan rode beside on the way to Capitol Hill was a friend of his, for he had served President Pierce as United States Minister to England. The friends of Buchanan had high hopes for him, for, said they, he was a schooled diplomat, a shrewd lawyer of unimpeachable probity and a former Senator.

The platform of 1856 upon which this Democratic nominee had conducted his campaign had swept him to victory over Pierce and Douglas for the nomination. He was chosen by a plurality vote over the opposing candidates, Fillmore and Gen. Fremont.

The Buchanan inauguration is described as being one of the most brilliant. Outstanding in the parade were a miniature ship of war and “the Keystone Club.” and a woman dressed as the Goddess of Liberty was given high place. The mayor of Washington delivered an address of welcome, and for the inaugural ball a special wooden building was erected in Judiciary Square, adjoining the City Hall.

This description has been given of his pretty niece, whose money has gone to give him this Meridian Hill Park memorial:

“Miss Lane is rather below the medium height, but has a fine figure and is of that blonde type of Saxon beauty so familiar to Christendom since the multiplication of portraits of Queen Victoria. She wore a white dress trimmed with artificial flowers, similar to those which ornamented her hair, and clasping her throat was a necklace of many strands of seed pearls.”

Such was her appearance on that gay inaugural day back in 1857. Mrs. Pierce, the retiring First Lady, had been ill, so that social Washington looked forward with anticipation to enjoying a brilliant round of events during the Buchanan administration —and it was not disappointed. Eminent social gatherings were revived after the gloom that pervaded the presidential mansion during the Pierce regime, due to the indifferent health of his wife.

The striking costume of the Russian Minister Stoekl aroused admiration and interest at the diplomatic receptions, but the Buchanan administration was to witness eminent foreigners at the White House from East and from West. The year of 1860 is set down in the history books as one of the most eventful of the quartet. The Prince of Wales, later to go down to posterity as Edward VII, arrived at the White House in October. An eventful state dinner was held, and fireworks were displayed for the entertaining of the guests. Miss Lane danced with the Prince, and around the teacups in Washington even yet there is told the tale of the wind swaying the candles in the chandeliers, sprinkling some of the guests with tallow.

The Prince and his party went aboard the revenue cutter Harriet Lane, named for Buchanan's niece, and took a trip down the Potomac River to Mount Vernon. The Prince traveled in those days as Baron Renfrew.

But there was another great event at the White House about that time, for the first Japanese envoys were presented in the Executive Mansion, and their curious Oriental raiment excited wide interest. They brought special gifts for President Buchanan, and they keenly observed how things were done in the Capital of the great country of the Occident. It is related that they were astounded at the way President Buchanan shook hands with the common folk, for their Emperor would never have done such a thing.

During the hot weather Buchanan had a cottage near the Sodiers' Retreat, but even there he was troubled by office seekers.

Those were stirring times in the internal life of the Nation. While observers said that Miss Lane had the faculty of making visitors feel at home, Buchanan was bitterly criticized by his enemies for his social activities, and some of them went so far as to contend that his functions were more like a republican court than the affairs of a democracy.

The fifteenth President of the United States, as Buchanan was, occupied the White House at a highly important juncture of the Nation's affairs. The famous Dred Scott case, in which the right of slavery was upheld, was handed down in those days; John Brown conducted his great raid on Harpers Ferry; agitation was rife, and already there were the rumblings of secession. His enemies upbraided him for his weakness and indecision and shouted that the country was drifting into open revolt.

This man Buchanan, who sits in bronze in Meridian Hill Park now, possessed an interesting background. Born April 23, 1791, in Cove Gap, near Mercersburg, Franklin County, Pa., Buchanan was graduated from Dickinson College in 1809. The law appealed to him and he was admitted to the bar in 18l2.

Serving under Judge Shippen in the defense of Baltimore, Buchanan was one of the first volunteers in the War of 18l2. Soon he was chosen a member of the House of Representatives from his native State and he served as a Federalist in the Seventeenth, Eighteenth, Nineteenth, Twentieth and Twenty-first Congresses—from March 4, 1821, to March 3, 1831. From June, 1832, to August. 1834, he was Minister to Russia and has been credited with negotiating the first commercial treaty with that country for the United States.

As a Democrat. Buchanan was chosen to sit in the United States Senate and served in that body from December 6, 1834, to March 5, 1845, when he resigned.

In the cabinet of President Polk he served as Secretary of State from March 6, 1845, to March 7, 1849, but the presidency of Gen. Taylor retired him to private life. He was summoned again to public service, however, by President Pierce, the erstwhile general, who appointed Buchanan to represent the Republic at London.

Following his own service in the White House, he retired to his beloved Wheatland, near Lancaster, Pa., to spend his last days in quiet. One of his last official public acts was to accompany the Great Emancipator, his successor in the presidential chair, to the Capitol. On that eventful March 4, 1861, Buchanan went up to the Capitol to sign last-minute legislation, just as the Presidents of today do. Lincoln and Buchanan entered the Capitol arm in arm and Chief Justice Taney administered the oath of office.

Then Buchanan retired from Washington life and wrote for the world an account of his administration, which has been bombarded by the critics without mercy. During his latter days Buchanan did some newspaper work, as a contributing editor, but he did not return to the bright lights of active politics. He died June 1, 1868, and was buried in Woodward Hill Cemetery, near Lancaster, Pa., which honored his memory, the day of the unveiling of his memorial here, in fitting fashion.

The Buchanan family traced its antecedents to Scotland and Ireland. James Buchanan emigrated to the United States from the northern section of Ireland in 1783 and settled in Pennsylvania. James, his eldest son, was destined to become the fifteenth President of the United States. Jane, the President's favorite sister and his playmate of childhood, in 1813 married Elliot T. Lane, a well-to-do merchant of English stock, who had settled in Virginia. In 1833, Harriett, their youngest child, was born in Mercersburg and spent her childhood in that vicinity.

BETWEEN the bachelor uncle and the charming niece grew up a sacred bond of affection. Later, when he was in the White House, she was to be the First Lady of the Land for him, and then, when he was cold in death and his enemies were still heatedly abusing his memory, she made up her mind that she would leave sufficient funds to erect a monument to him —and history has just seen her wish come true.

Harriet Lane's mother died when she was about 7 years of age, and about two years later her father passed away. Then her beloved uncle took her In hand and reared her. After she had grown into beautiful womanhood and her golden hair and violet eyes had spread their charm, she met her future husband, Henry Elliot Johnston of Baltimore, when she and Mr. Buchanan were on a visit to Bedford Springs They were married in 1866, just two years before Mr. Buchanan's death.

Her husband died in 1883 and the two children born to her died before reaching their majority. James Buchanan Johnston died at the age of 15, while her other son, Henry Elliot Johnston, died at 12 at Nice.

Mrs. Harriet Lane Johnston resided during the latter part of the last century at Eighteenth and I streets and in those days she found time to collect the paintings that were destined to form the nucleus for the National Gallery of Art here. Olden residents of Washington remember her well, a queenly figure, clad in black velvet, wearing becomingly her choice pearls and her dazzling diamonds. She held a court of her own, reminiscent of those brilliant days of '57 to '6l, at her residence here, but her fame traveled far, for she was a great favorite of Queen Victoria.

By special Invitation, she attended the coronation of King Edward VII, who as Prince of Wales had visited her, back in the days of youth of '60. As Buchanan was the first bachelor President of the Nation, so, too, was Harriet Lane the first maiden to serve as First Lady of the Land. She died in Rhode Island on July 3, 1903.

In her will she made provision for the monument that stands today in Meridian Hill Park and she wrote the words that should be placed upon it, quoting what Hon. Jeremiah S. Black had said of Buchanan: “The Incorruptible statesman whose walk was upon the mountain ranges of the law.”

Out of her estate, estimated at more than $1,000,000, she directed that a Buchanan Memorial Fund be established and as trustees for this money, she named William A. Fisher of Baltimore, Calderon Carlisle and E. Francis Riggs of Washington and Lawrason Riggs of Baltimore. Gen. Lawrason Riggs, who took a prominent part in the preparation of the memorial, is the only surviving trustee.

In her will Mrs. Johnston decreed that if Congress failed to provide a site for the erection of a statue to President Buchanan within 15 years after her death, the sum of $100,000 “and its increments” should go to the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children of Baltimore. Fifteen years after her death was marked by July 3, 1918, and it was not until June 27, 1918, within a week before the “deadline.” that an act was signed, making provision for the monument, to be erected on suitable public site.

THE debates of those nervous, war-torn days of the middle of 1918 reveal that bitterness towards Buchanan has not died with the years. The late Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts vigorously opposed the erection of a statue to this man in this city. On Flag day, 1918, Senator Smith of Maryland, seeking to defend the memory of Buchanan, told the Senate:

“Buchanan was confronted with enormous difficulties when President. Mexico, then, as recently, was a source of deepest concern; likewise Cuba. Every indication pointed to a disruption of the country, to a civil war, that any President must have strained every nerve and energy, compromised in any honorable way to avoid. Imagine the responsibility. Imagine any one, whatever his ability, postponing indefinitely, much less averting entirely, that strife. Omnipotent power, omniscient skill alone could have warded off the Civil War. Of course Buchanan made mistakes. Any one would. Of course he failed. Any one would. Of course he displeased and disappointed many people, many powerful factions. Any one would. Of course he was subjected to vile, harsh abuse. So was Washington, and so, indeed, was every President.

“But none can say he did not act in good conscience, from pure motives, and in accord with the moral standard, the idea of law and rights that then obtained among the majority of the American Nation.

“He did that which his conception of his oath, the law. and his duty required of him always.

“Mr. Buchanan not not the gratest of our Presidents, or yet the least. In patriotism, in moral character and intellect he measured above the average by far. His perplexities were terrible. We are not just if we censure him for falling where no finite genius could succeed, as now we well know. * * *

“Slavery, secession—both dead. Why not let the discussion of the painful memories, the dark history of their period die?”

With references to Mrs. Johnston, Senator Smith said:

“Mrs. Johnston, his niece, a philanthropist who has endowed a great hospital in Baltimore for the treatment of little suffering children and also helpful in other charities, honored and respected Buchanan. Her philanthropies, however, were not in Baltimore alone. She did many other philanthropic acts, among which is included the presentation to the Smithsonian Institution of her large and magnificent collection of paintings to form a nucleus of a National Art Gallery. She was the hostess and mistress of the White House during his administration. No man who was unworthy

could have held until death the love and respect of a woman of such culture and intellectuality. * * *

“Few men in America have done what Buchanan did for his country. From 1814 until 1861 he was in public life. He served in the Legislature of Pennsylvania in 1814. For 10 years he was a Representative in Congress, and in 1832 he was appointed an envoy to Russia by President Jackson and rendered signal service in negotiating a commercial treaty with that country. He sat for three terms in this Senate, and declined the Attorney Generalship of the United States, offered him by President Van Buren. He served with success and distinction as Secretary of State under President Polk and was appointed our Minister to England by President Pierce. His was a long, honorable, and most useful career. Never in his long political life did the breath of scandal touch him. Only for his openly held and courageously expressed political views was he assailed.”

The Washington of tomorrow will gaze with wonder upon this monument, the work of the sculptor Hans Schuler, and the architect William Gordon Beecher. In the east end of the lower garden the great bronze statue of Buchanan will sit, listening, as it were, to the tumbling of the water down the cascade into the pleasant pod, below—but in reality, perhaps, thinking of Clay, of Calhoun, of Webster and of Fort Sumter and Appomattox, but above all, of a golden-haired lass of the 'sixties

—Harriet Lane.

Monument to America's First Bachelor President, by William A. Millen, The Sunday Star, Washington, D. C, July 13, 1930. (PDF)