Collier's Weekly, April 1903

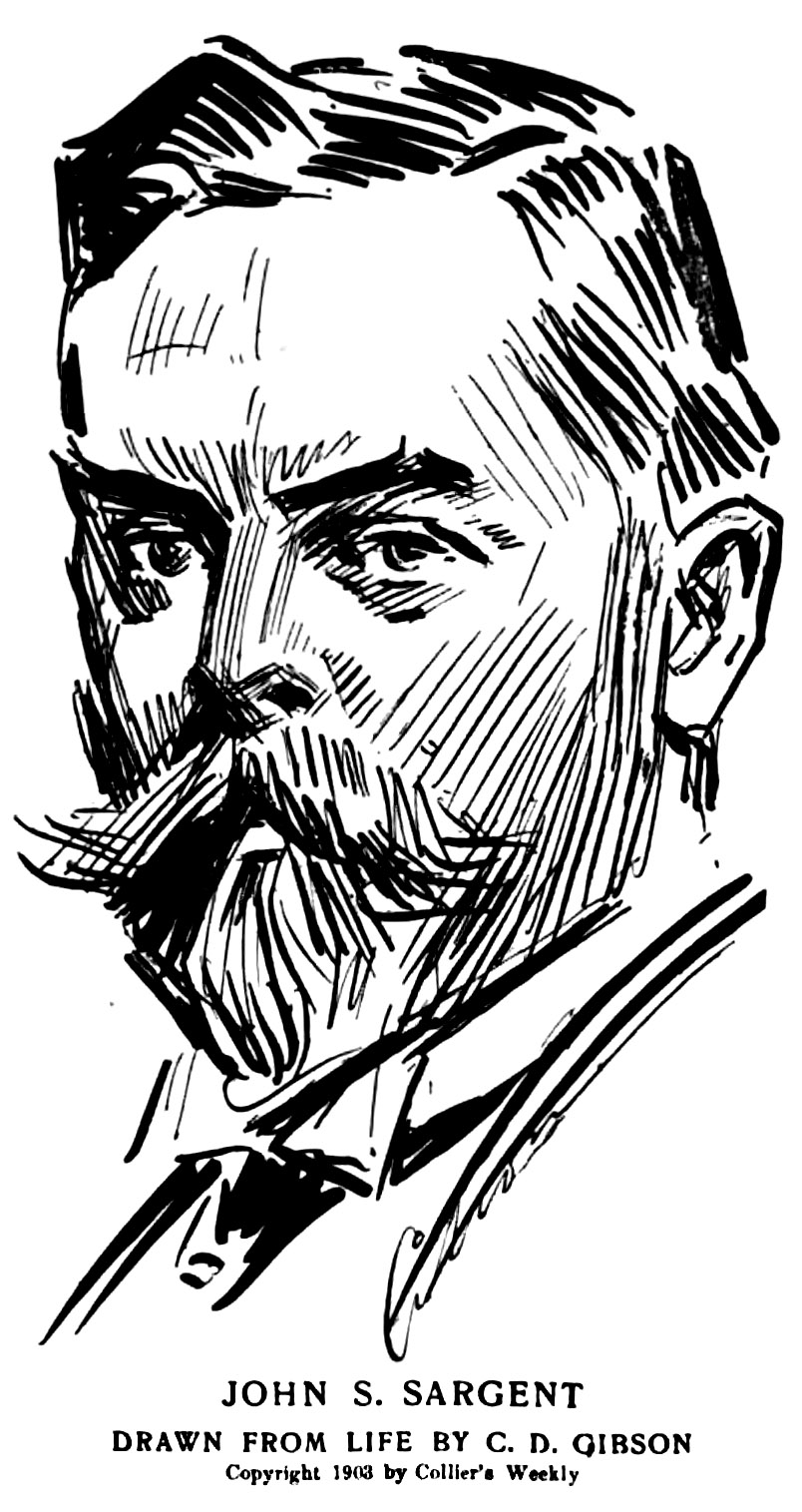

John Singer Sargent:

An Appreciation

By Charles H. Caffin

MR. SARGENT'S present visit to this country is doubly signalized. He has installed a great decoration in the Boston Public Library and has painted the portrait of the President.

One has detected of late some rumbles of dissatisfaction that the highest official recognition in the land should have been given to a foreign portrait-painter, and I have heard some extreme patriots declare, not very reasonably perhaps, that no President should permit himself to be painted by any but an American.

In the present case, however, Mr. Roosevelt has satisfied every one.

He has been painted by one who is not only an American, but the most brilliant of living portrait-painters, and the result is a picture of magnificent distinction.

The conjunction of artist and subject on this occasion was more than usually fortunate. Mr. Roosevelt's exterior is singularly indicative of his character. In the square erectness of pose —the figure, if you notice, firmly planted on both feet —in the breadth of the shoulders and in the strength and alertness of the head, are visibly pronounced the traits of physical and intellectual manhood which make him respected even bv those who do not love him politically. To the eye of Sargent, so extraordinarily keen in summarizing the tout ensemble of a personality, to the exclusion sometimes not even of its weaknesses, the character in this one would appeal irresistibly. Indeed, from its virility his own virile and masterful manner would receive more than ordinary inspiration. As a consequence this portrait, so far as one can judge from the reproduction, will rank among the artist's most spirited and spontaneously forceful works. And is it not an example of his intuition and tactfulness in imagining a picture, that he should have set the figure in dark Silhouette against a light background? Instead of bringing them nearer together in some more obvious tonal arrangement, he has by contrast secured for the figure additional insistence and authority.

Equally suggestive of his tact is the entire absence of any exaggeration in the force of the picture. It is great without being grandiose, forceful with the quietness of concentration. A similar grandeur of reserve characterizes Sargent's new decoration in the Boston Library. The theme it embodies is the “Dogma of Redemption,” chapter in the series which commemorates the Evolution of Christianity. The treatment follows the traditions of Byzantine art, which are at once peculiarly adapted to the noblest kind of mural decoration and in most intimate relation to the symbolism which forms so conspicuous a feature of the presentation. Indeed, it is through the early symbolism, still reserved by the Church, that the artist has portrayed the subject.

The central figure is the Christ upon the Cross, beneath His extended arms being the crouching figures of Adam and Eve, holding chalices to catch the Sacred Blood, while at the foot of the Cross is a pelican piercing her breast to nourish her brood, a symbol of the divine Sacrifice. All these figures are modelled in high relief. Above the Christ are seated the three Persons of the Trinity, their crimson draperies showing against a background of deep blue. Below, the Cross is supported by two angels, on each side of whom are figures bearing the symbols of the Passion, forming a band across the bottom of the painting, so that they correspond with the frieze of the Prophets in the earlier decoration at the other end of the hall. The scheme of color is blue and crimson, gray in the high lights and copiously embellished with gold, the whole toned to a dull lustre as of some painting that the ages have mellowed.

As a decoration the work is superbly handsome; with a noble ampleness of composition, and with indescribable subtlety in the various degrees of relief work introduced upon the flat surface. It has, too, the distinction of simplicity; representing, in this respect, a more matured accomplishment than the pendant at the other end of the hall, executed eight years ago. The simplicity reveals itself in the conception and in the massing; for in its details this work is, perhaps, even richer than the earlier one; at least the enrichment is more nobly assertive.

Strong Originality

Again, most remarkable is the fact that, while the artist has drawn his inspiration from primitive sources, he has contrived to infuse into his work a portion of the modern feeling. On the one hand, he has avoided the banality of merely imitating the mediaeval manner, arid on the other has not lost touch of the spirit which it enshrined. It is here that he has revealed the possession of imagination, sufficiently fresh and living to be actually creative. For a creation in the most real sense is this decoration. It involves material and ideas with which every student of religious painting and symbolism is familiar, and yet with a novelty and reasonableness of appeal that are quite extraordinary. For in no previous work has he risen to such a height of artistic dignity or of emotional and intellectual appeal.

To myself, for one can speak best of one's own impressions, the decoration brought one of those sensations, experienced only at rare intervals in the study of pictures, where one's whole imagination is caught up and set on a level infinitely above itself. I ask myself the question: What does the work portend to the artist? He has reached long since the highest position as a portrait-painter, most probably the highest of which he is capable. In the vicissitudes of a life spent in the portrayal of fashionable people, many a subject presents itself unworthy of his skill, levying heavy exactions upon his strength and blunting the freshness of his imagination. For perhaps some people do not realize the fearful strain under which a portrait-painter of Sargent's sensibility and conscientiousness must labor, compared with which the painting of so congenial a subject as the President is a delightful sport. Is the game worth the candle? Fortune is his, and fame, unrivalled in this particular branch. Meanwhile, in another he has proved himself a master, also without living rival, and it is one in which he can without obstacle develop the highest possibilities within himself. That they are greater than those he has reached even in his most brilliant portraits, few, if any, of the admirers of his latest decoration will doubt. Indeed, it will seem to them that Sargent has reached a point on the road of his career where he might well part company with the distractions and limitations of a fashionable portrait-painter and allow free rein to his imagination. He made himself first known to London some eighteen years ago by a work of exquisite imagination, “Carnation Lily, Lily Rose”; he has proved himself possessed of the grander qualities of imagination in this latest work at Boston. Can he hesitate as to the true direction in which his genius prompts?

John Singer Sargent: An Appreciation by Charles H. Caffin, Collier's Weekly April 1903, Vol XXX No 26 page 30. (PDF)