Historical Collections of Ohio, Vol. II.

by Henry Howe

Johnny Appleseed

At an early day, there was a very eccentric character who frequently was in this region, well remembered by the early settlers. His name was John Chapman, but he was usually known as Johnny Appleseed. He came originally from New England.

He had imbibed a remarkable passion for the rearing and cultivation of apple trees from the seed. He first made his appearance in western Pennsylvania, and from thence made his way into Ohio, keeping

on the outskirts of the settlements, and following his favorite pursuit. He was accustomed to clear spots of the streams, plant his seeds, enclose the ground, and then leave the place until the trees had in measure grown. When the settlers began to flock in and open their “clearings,” Johnny was ready for them with his young trees, which he either gave away or sold for some trifle, as an old coat, or any article of which he could make use. Thus he proceeded for many years, until the whole country was in a measure settled and supplied with apple trees, deriving self-satisfaction amounting to almost delight, in the indulgence of his engrossing passion. About 20 years since he removed to the far west, there to enact over again the same career of humble usefulness which had been his occupation here.

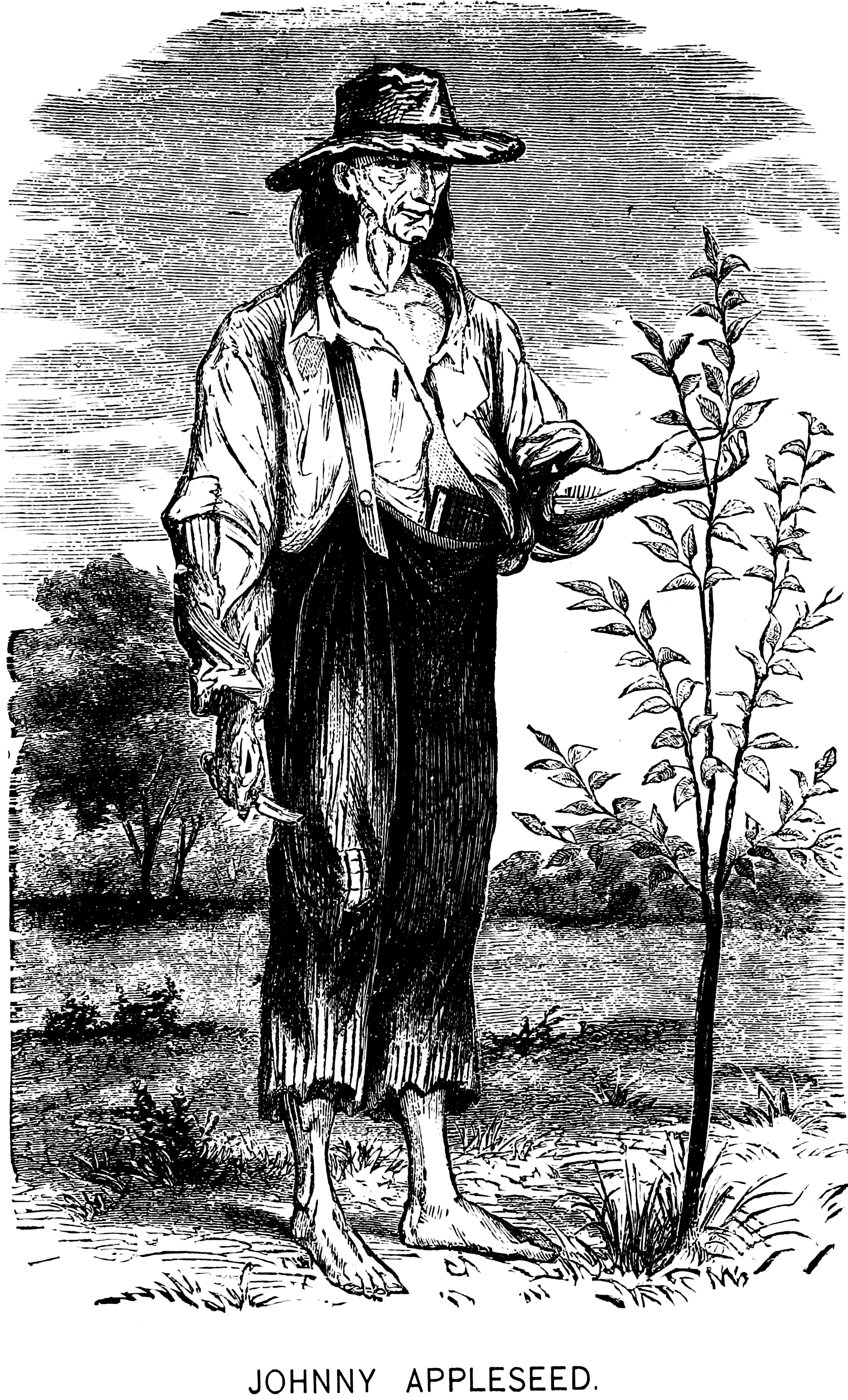

His personal appearance was a singular as his character. He was quick and restless in his motions and conversation; his beard and hair were long and dark, and his eye black and sparkling. He lived the roughest life, and often slept in the woods. His clothing was mostly old, being generally given to him in exchange for apple trees. He went bare-footed, and often travelled miles through the snow in that way. In doctrine he was a follower of Swedenborg, leading a moral, blameless life, likening himself to the primitive Christians, literally taking no thought for the morrow. Wherever he went he circulated Swedenborgian works, and if short of them would tear a book in two and give each part to different persons. He was careful not to injure any animal, and thought hunting morally wrong. He was welcome everywhere among the settlers, and was treated with great kindness even by the Indians. We give a few anecdotes, illustrative of his character and eccentricities.

On one cool autumnal night, while lying by his camp-fire in the woods, he observed that the mosquitoes flew in the blaze and were burnt. Johnny, who wore on his head a tin utensil which answered both as a cap and a mush pot, filled it with water and quenched the fire, and afterwards remarked, “God forbid that I should build a fire for my comfort, that should be the means of destroying any of His creatures.” Another time he made his camp-fire at the end of a hollow log in which he intended to pass the night, but finding it occupied by a bear and cubs, he removed his fire to the other end, and slept on the snow in the open air, rather than disturb the bear. He was one morning on a prairie, and was bitten by a rattlesnake. Some time after, a friend inquired of him about the matter. He drew a long sigh, and replied, “Poor fellow! he only just touched me, when I, in an ungodly passion, put the heel of my scythe on him and went home. Some time after I went there for my scythe, and there lay the poor fellow dead.” He bought a coffee bag, made a hole in the bottom, through which he thrust his head and wore it as a cloak, saying it was as good as anything. An itinerant preacher was holding forth on the public square in Mansfield, and exclaimed, “Where is the bare-footed Christian, travelling to heaven!” Johnny, who was lying on his back on some timber, taking the question in its literal sense, raised his bare feet in the air, and vociferated “Here he is!”

The foregoing account of this philanthropic oddity is from our original edition. In the appendix to the novel, by Rev. James McGaw, entitled “Philip Seymour; or, Pioneer Life in Richland County,” is a full sketch of Johnny, by Miss Rosella Price, who knew him well. When the Copus monument was erected. she had his name carved upon it in honor of his memory. We annex her sketch of him in an abridged form. The portrait was drawn by an artist from her personal recollection, and published in A. A. Graham's “History of Richland County.”

Johnny Appleseed's Relatives.—John Chapman was born at or near Springfield, Mass., in the year 1775. About the year 1801 he came with his half-brother to Ohio, and a year or two later his father's family removed to Marietta, Ohio. Soon after Johnny located in Pennsylvania, near Pittsburg, and began the nursery business and continued it on west. Johnny's father, Nathaniel, senior, moved from Marietta to Duck creek, where he died. The Chapman family was a large one, and many of Johnny's relatives were scattered throughout Ohio and Indiana.

Johnny was famous throughout Ohio as early as 1811. A pioneer of Jefferson county said the first time he ever say Johnny he was going down the river, in 1806, with two canoes lashed together, and well laden with apple-seeds, which he had obtained at the cider presses of Western Pennsylvania. Sometimes he carried a bag or two of seeds on an old horse; but more frequently he bore them on his back, going from place to place on the wild frontier; clearing a little patch, surrounding it with a rude enclosure, and planting seeds therein. He had little nurseries all through Ohio, Pennsylvania and Indiana.

How Regarded by the Early Settlers.—I can remember how Johnny looked in his queer clothing—combination suit, as the girls of now-a-days would call it. He was such a good, kind, generous man, that he thought it was wrong to expend money on clothes to be worn just for the fine appearance; he thought if he was comfortably clad, and in attire that suited the weather, it was sufficient. His head-covering was often a pasteboard hat of his own making, with one broad side to it, that he wore next the sunshine to protect his face. It was a very unsightly object, to be sure, and yet never one of us children ventured to laugh at it. We held Johnny in tender regard. His pantaloons were old, and scant and short, with some sort of a substitute for “gallows” or suspenders. He never wore a coat except in the winter-time; and his feet were knobby and horny and frequently bare. Sometimes he wore old shoes; but if he had none, and the rough roads hurt his feet, he substituted sandals—rude soles, with thong fastenings. The bosom of his shirt was always pulled out loosely, so as to make a kind of pocket or pouch, in which he carried his books.

Johnny's Nurseries.—All the orchards in the white settlements came from the nurseries of Johnny's planting. Even now, after all these years, and though this region of country is densely populated, I can count from my window no less than five orchards, or remains of orchards, that were once trees taken from his nurseries.

Long ago, if he was going a great distance, and carrying a sack of seeds on his back, he had to provide himself with a leather sack; for the dense underbrush, brambles and thorny thickets would have made it unsafe for a coffee-sack.

In 1806 he planted sixteen bushels of seeds on an old farm on the Walhonding river and he planted nurseries in Licking county, Ohio, and Richland county, and had other nurseries farther west. One of his nurseries is near us, and I often go to the secluded spot, on the quiet banks of the creek, never broken since the poor old man did it, and say, in a reverent whisper, “Oh, the angels did commune with the good old man, whose loving heart prompted him to go about doing good!”

Matrimonial Disappointment.—On one occasion Mrs. Price's mother asked Johnny if he would not be a happier man, if he were settled in a home of his own, and had a family to love him. He opened his eyes very wide—they were remarkably keen, penetrating grey eyes, almost black—and replied that all women were not what they professed to be; that some of them were deceivers; and a man might not marry the amiable woman that he thought he was getting, after all. Now we had always heard that Johnny had loved once upon a time, and that his lady love had proven false to him. Then he said one time he saw a poor, friendless little girl, who had no one to care for her, and sent her to school, and meant to bring her up to suit himself, and when she was old enough he intended to marry her. He clothed her and watched over her; but when she was fifteen years old, he called to see her once unexpectedly, and found her sitting beside a young man, with her hand in his, listening to his silly twaddle. I peeped over at Johnny while he was telling this, and, young as I was, I saw his eyes grow dark as violets, and the pupils enlarge, and his voice rise up in denunciation, while his nostrils dilated and his thin lips worked with emotion. How angry he grew! He thought the girl was basely ungrateful. After that time she was no protogé of his.

His Power of Oratory.—On the subject of apples he was very charmingly enthusiastic. One would be astonished at his beautiful description of excellent fruit. I saw him once at the table, when I was very small, telling about some apples that were new to us. His description was poetical, the language remarkably well-chosen; it could have been no finer had the whole of Webster's “Unabridged,” with all its royal vocabulary, been fresh upon his ready tongue. I stood back of my mother's chair, amazed, delighted, bewildered, and vaguely realizing the wonderful powers of true oratory. I felt more than I understood.

His Sense of Justice.—He was scrupulously honest. I recall the last time we ever saw his sister, a very ordinary woman, the wife of an easy old gentleman, and the mother of a family of handsome girls. They had started to move West in the winter season, but could move no farther after they reached our house. To help them along and to get rid of them, my father made a queer little one-horse vehicle on runners, hitched their poor little caricature of a beast to it; helped them to pack and stow therein their bedding and a few movables; gave them a stock of provisions and five dollars, and sent the whole kit on their way rejoicing; and that was the last we ever saw of our poor neighbors. The next time Johnny came to our house he very promptly laid a five-dollar bill on my father's knee, and shook his head very decidedly when it was handed back; neither could he be prevailed upon to take it again.

He was never known to hurt any animal or to give any living thing pain—not even a snake. The Indians all liked him and treated him very kindly. They regarded him, from his habits, as a man above his fellows. He could endure pain like an Indian warrior; could thrust pins into his flesh without a tremor. Indeed so insensible was he to acute pain, that his treatment of a wound or sore was to sear it with a hot iron, and then treat it as a burn.

Mistaken Philanthropy.—He ascribed great medicinal virtue to the fennel, which he found, probably, in Pennsylvania. The overwhelming desire to do good and benefit and bless others induced him to carry a quantity of the seed, which he carried in his pockets, and occasionally scattered along his path in his journeys, especially at the wayside near dwellings. Poor old man! he inflicted upon the farming population a positive evil, when he sought to do good; for the rank fennel, with its pretty but pungent blossoms, lines our roadsides and borders our lanes, and steals into our door-yards, and is a pest only second to the daisy.

Leaves His Old Haunts.—In 1838 he resolved to go farther on. Civilization was making the wilderness to blossom like the rose; villages were springing up; stagecoaches laden with travellers were common; schools were everywhere; mail facilities were very good; frame and brick houses were taking the places of the humble cabins; and so poor Johnny went around among his friends and bade them farewell. The little girls he had dandled upon his knees and presented with beads and gay ribbons, were now mothers and the heads of families. This must have been a sad task for the old man, who was then well stricken in years, and one would have thought that he would have preferred to die among his friends.

He came back two or three times to see us all, in the intervening years that he lived; the last time was in the year that he died, 1845.

His bruised and bleeding feet now walk the gold-paved streets of the New Jerusalem, while we so brokenly and crudely narrate the sketch of his life—a life full of labor and pain and unselfishness; humble unto self-abnegation; his memory glowing in our hearts, while his deeds live anew every springtime in the fragrance of the apple-blossoms he loved so well.

An account of the death and burial of this simple-hearted, virtuous, self-sacrificing man, whose name deserves enrolment in the calendar of the saints, is given on page 260, Vol. I.

The following extract from a poem, by Mrs. E. S. Dill, of Wyoming, Hamilton county, Ohio, written for the Christian Standard, is a pleasing tribute to the memory of Johnny Appleseed:

Grandpa stopped, and from the grass at our feet,

Picked up an apple, large, juicy, and sweet;

Then took out his jack-knife, and, cutting a slice,

Said, as we ate it, “Isn't it nice

To have such apples to eat and enjoy?

Well, there weren't very many when I was a boy,

For the country was new—e'en food was scant;

We had hardly enough to keep us from the want,

And this good man, as he rode around,

Oft eating and sleeping upon the ground,

Always carried and planted appleseeds—

Not for himself, but for others' needs.

The appleseeds grew, and we, to-day,

Eat of the fruit planted by the way.

While Johnny—bless him—is under the sod—

His body is—ah! he is with God;

For, child, though it seemed a trifling deed,

For a man just to plant an appleseed,

The apple-tree's shade, the flowers, the fruit,

Have proved a blessing to man and to brute.

Look at the orchards throughout the land,

All of them planed by old Johnny's hand.

He will forever remembered be;

I would wish to have all so think of me.”

Johnny Appleseed, Historical Collections of Ohio, by Henry Howe, Vol. II, 1904, Pages 484-487.(PDF)