The Morning News. Sunday, July 21, 1901.

Billions in His Trade

HOW MARTIN SUCCEEDS IN MAKING A COMFORTAIBLE LIVING.

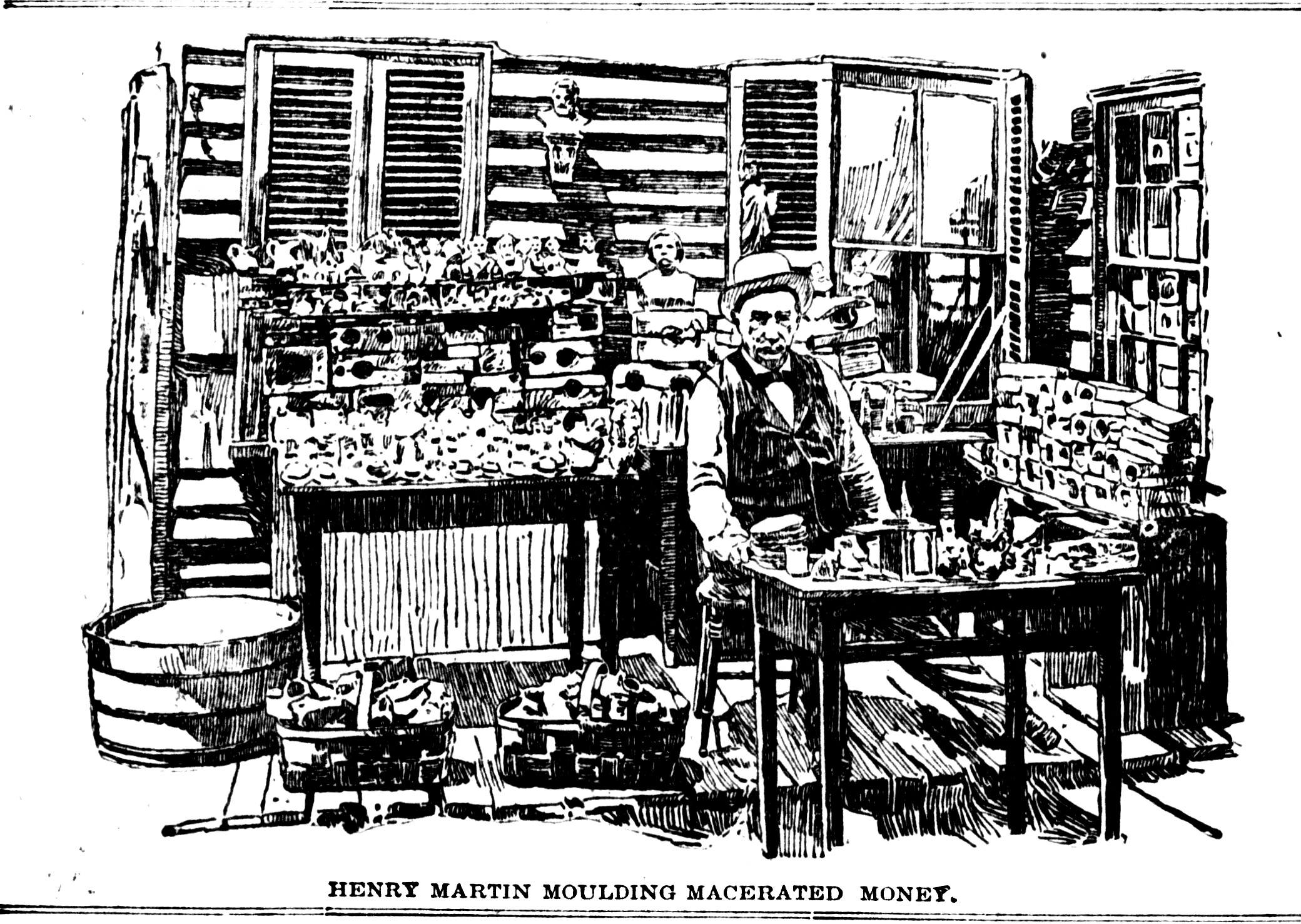

By a Special Arrangment He is Allowed to Buy From the Treasury as Much as He Wants of its Macerated Greenbacks, and This Pulp He Models Into Statuettes of Many Kinds. Which Are Sold as Souvenirs in Washington —Small Models of the Washington Monument Represent $5,000 Each, in Bills. While a Good-Sized Bust of Grant Takes $200,000 and Half Life Size of Gen. Logan Uses Up Half a Million Dollars—Nothing in the Appearance of the Statuettes Indicates That They Were Ever Money.

Copyright 1901 by Waldon Fawcett.,

Washington, July 19.—In a quaint little workshop under the shadow of the Capitol at Washington there toils all day, and usually far into the night; as well, a man who handles every day In the year more money than passes through the hands of any bank official in the country. Indeed this industrious artisan claims to have had in his care more of Uncle Sam's greenbacks than have been entrusted to any other person, with the possible exception of a few officials of the Treasury Department. Finally this money manipulator, who ranks as one of the “characters” of Washington, has an absolutely unique occupation—is possibly the only man in the United States who has during nearly a score of years preserved his field of labor secure from invasion by any other man. His craft is the molding of macerated money, which, being interpreted, means that he takes the government's worn out currency after it has been torn and ground into an unrecognizable mass and fashions it into busts and medallions of prominent persons much as a sculptor might cast a figure in bronze. These queer little statuettes, which resemble nothing else on earth, constitute the most novel curious to be found in the shops of what might justly be termed the city of souvenirs. The designs in pulverized Money have never had any sale in other cities, although the experiment has been tried, for the reason that people refuse to believe that the material was actually money, or, in some cases, were even incredulous that the government ever destroyed so much money, but nine out of every ten visitors to Washington will go to the bowels of the treasury building and see tons of worn out money chewed up by the mechanical gourmand kept there for that purpose, straightway pay over their new money for the old money dealt in by the vendors of these mementoes.

Years ago the Treasury officials followed the custom of dumping the discarded money, after it had been torn into tiny bits, on the vacant lot at the rear of the White House, but this proved an extensive practice for the nation. The great heap continually swarmed with lynx-eyed negro boys, who now and then discovered fragments of greenbacks of sufficient size to be used In exchange for good bills under the Treasury ruling, which provides that restitution shall he made for a damaged bill If enough of it remains intact to Indicate the denomination —stipulation made, of course, for the protection of persons who suffer losses by the burning or other partial destruction of greenbacks.

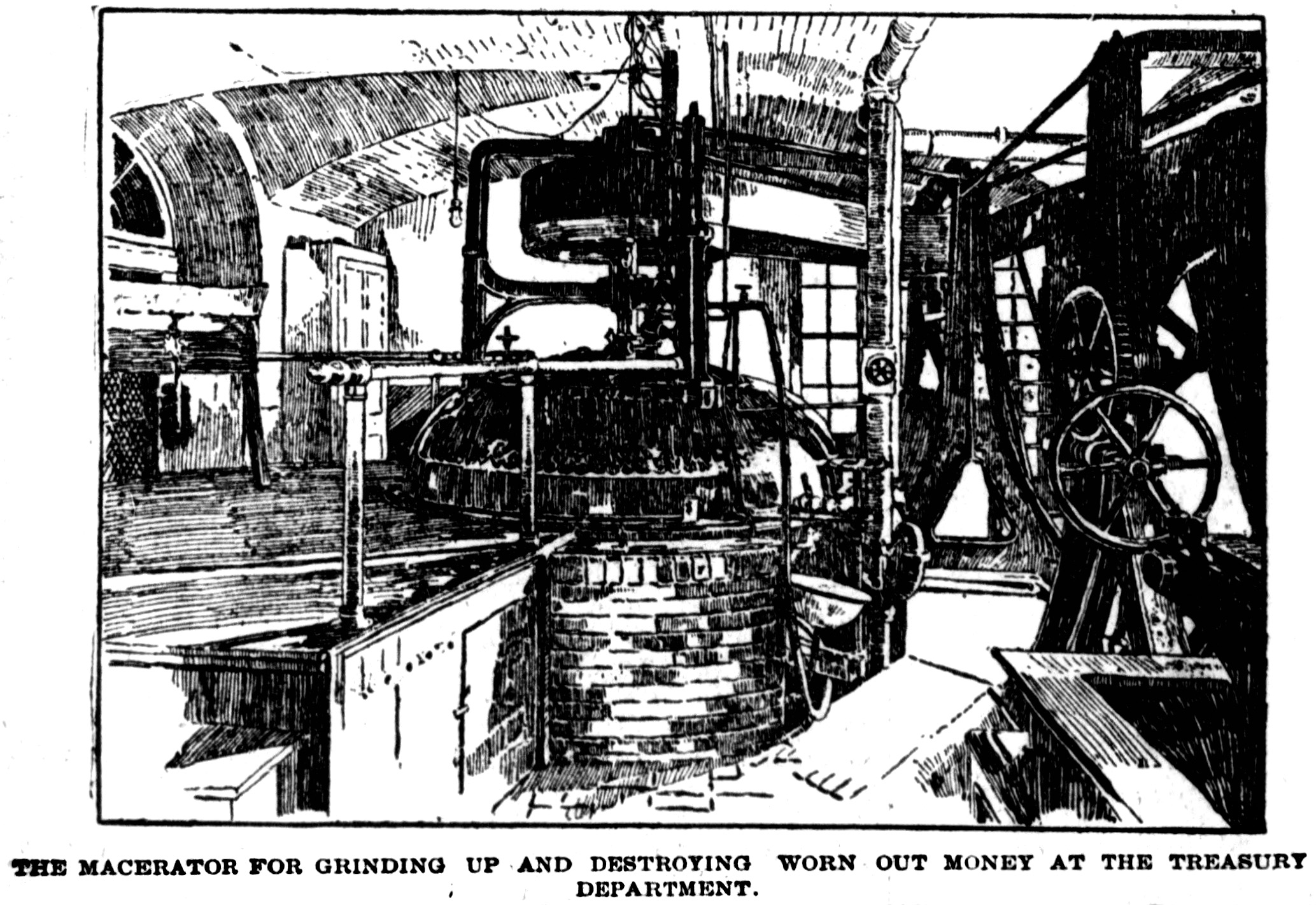

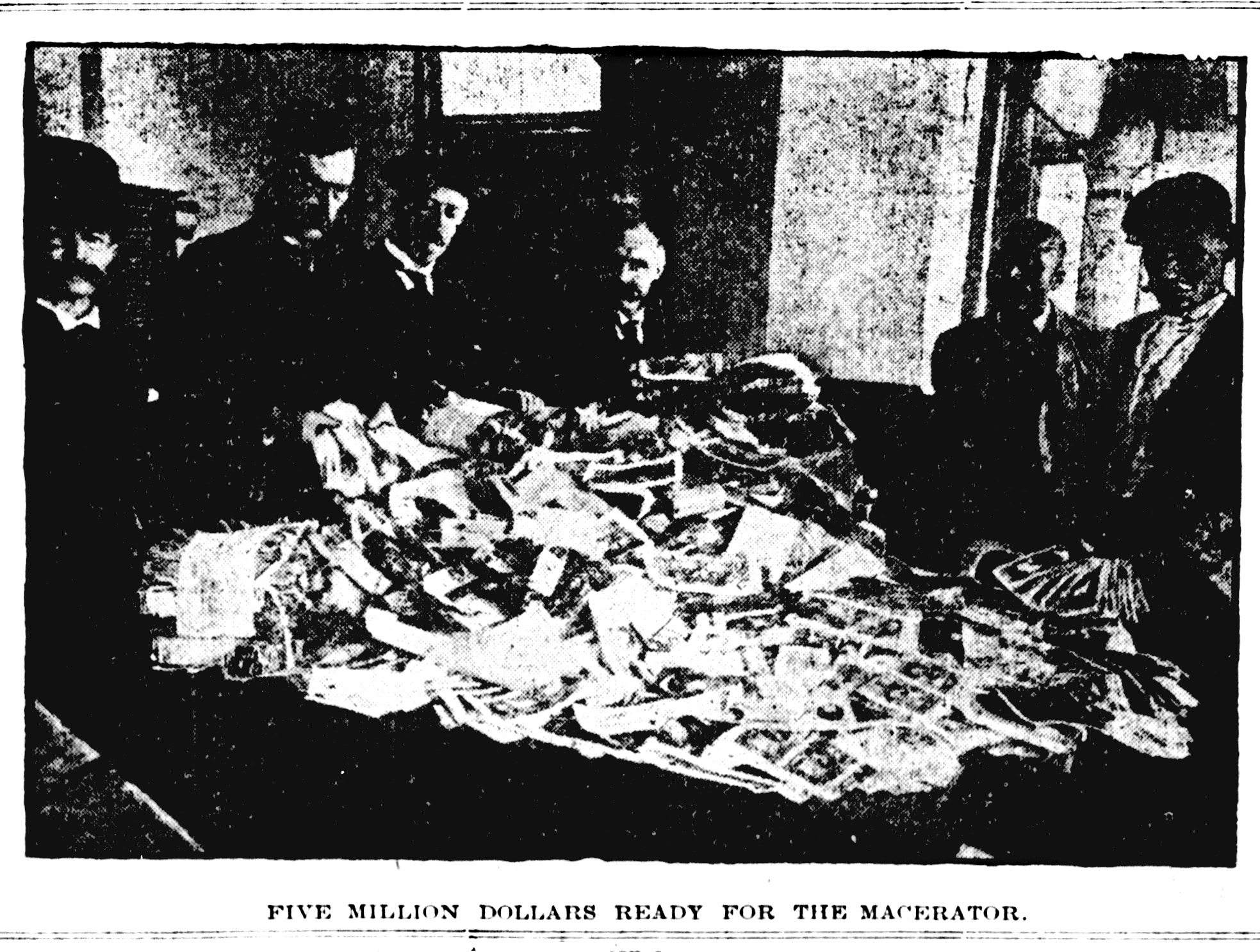

As a remedy for the evil just described the plan of burning the old money was Introduced, but even then it was found that fragments floated away and were put to ulterior uses, and so resort was made to the present practice of disposing of the macerated mass to manufactures to be converted Into paper once more. The privilege of securing the unsightly product of the macerator is awarded once each year to the highest bidder. Formerly the old man who models in this queer material was obliged to purchase his supplies from the contractors, but through the intervention of several senators a few years since he secured the privilege of purchasing such a quantity as he might desire direct from the Treasury. The macerated money put to this use is, however, a mere drop in the bucket as compared to the total output. The government machine crushes every month more than forty tons of retired currency, and little more than half a ton of this is required for modeling purposes.

This molder of concentrated wealth, Henry Martin, is a strange soldier of fortune who has had a career almost as extraordinary as the occupation in which he is now engaged. In his boyhood he was a sailor before the mast, in various English ships. A picture of the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac fired him with a desire to enter the American navy. Early in the sixties he worked his way to America, and failing to get in the navy, joined the army, and wound up with a siege in the hospital that cost him a limb. He helped In the rebuilding of Chicago that followed the great fire, spent three years in the saddle among the cow punchers of the West, and then drifted to Washington and served as watchman in the Treasury building until a turn of the political wheel of fortune threw him out.

It was in his term of service as one of the watchdogs of Uncle Sam's big money chests that Martin conceived the idea of turning the supposedly worthless macerated money to account in his own peculiar way. The stimulant for his inventive genius was the sight, one day, of a clerk who was possessed of some artistic ability moulding by hand a crude design for one of the Treasury officials who desired to preserve a wad of the dilapidated currency in this form. The quick witted watchman secured a key to the room in which the churnings of the macerator were stored, and night after night he pursued his self-instruction in sculpture until he was master of his strange medium.

The inventor's first efforts to turn his knack to commercial advantage did not meet with signal success. He lost $800 in eight months, but kept up the fight, and for more than eighteen years now Martin has scarcely been able to keep up with the demand for the interesting if not highly artistic trophies. His "studio" on Capitol Hill is not a very pretentious establishment but it is at least possessed of the attraction of novelty. The major part of the work is done by Martin himself, although several women are employed as helpers.

The macerated money is brought from the Treasury as often as occasion requires, half a ton at a time, and the uninitiated visitor would scarcely suspect that the large dry goods box packed to overflowing with a damp, greenish grayish mass constitutes, so far as Uncle Sam is concerned, the final resting place of $6,000,000. Immediately upon its arrival the macerated currency gets a thorough bath, a tedious operation, from which it emerges several shades lighter in tint. After it has been subjected to pressure to remove as much of the water as possible It Is hammered and pounded into plaster of paris models, and then, after another interval for drying, the completed trinket is smoothed and finished by hand. As may be imagined, the preparation of the moulds is the phase of the work requiring the highest skill. The bust or statuette is first modeled with great care in clay, and from this creation the plaster moulds are made. A mould may be used almost indefinitely, but occasionally at "rush" intervals when souvenirs are being turned out night and day to meet a holiday demand, the plaster of paris absorbs so much moisture that it is almost impossible to continue work.

The objects which have been modeled from this retired currency include busts and medallions of almost every man who has been prominent in the nation's history In the past quarter of a century, miniature reproductions of the Washington monument and some of the public buildings at the national capital; and innumerable fanciful creations. The veteran modeler estimates that he has made in all more than 50,000 macerated trophies of one kind or other, and has utilized in their formation several billions of dollars.

By weighing masses of the macerated pulp and comparing them with an equivalent hulk of paper money in condition for circulation estimates have been arrived at as to the amount of currency embodied In each of these governmental souvenirs. Of course, this is, necessarily an approximation, since a bit of macerated ware might perchance have been fashioned exclusively from S1,000 notes, but the figures are at least conservative enough, since they are based on the weight of $5 notes, the lowest denomination fed to the macerator. Tiny facsimiles of the Washington monument are supposed to contain $5,000; a good-sized bust of Grant requires $200,000 worth of the once prized paper, and a bust of Gen. Logan, half life size, embodies half a million dollars worth of transformed greenbacks.

Very frequently bits of greenbacks nearly as large as a man's thumb nail are found in the paper pulp, and sometimes a series number or the figure of a denomination is clearly discernible on a fragment of a greenback which has eluded the macerator. Formerly it was the custom to place such stray scraps prominently on the face of the relic as a sort of guarantee of its genuineness, but the government officials soon found that shrewd tricksters were seeking to make use of these bits, as they had done when the macerated money was dumped in the rear of the White House and they insisted that such scraps of paper be entirely eliminated on pain of refusing to sell any more pulp to the relic manufacturer.

The refuse of the nation's money making establishment has at one time or another attracted the attention of a good many of the clever men of the under world, and Mr. Martin has had some experiences in this connection that are almost as interesting as those of a secret service man. Some years ago a gang of counterfeiters who had experienced difficulty in imitating the paper on which the government currency is printed evolved an elaborate scheme for getting hold of quantities of the macerated money through Mr. Martin in the hope that it could be made into material that would have something of the same texture as the original, but the plan proved impracticable and came to naught.

Mr. Martin's most remarkable experience was with a Rhode Island banker some years since, and the publication of the incident would doubtless create something of a sensation in the smallest state in the Union were the name of chief actor made public. At the St. James Hotel in Washington one day the handler of macerated money was introduced by a casual acquaintance to a well-dressed man of excellent address. For days thereafter the new acquaintance appeared to be Martin's shadow and never lost an opportunity to proffer entertainment of one sort or other. Finally he asked and secured permission to visit the molding shop.

At the appointed time the Rhode Islander was shown the whole process of manufacture, but appeared all the while ill-satisfied, and finally at the close of the tour of Inspection said:

“But you have not shown me the very thing I am most anxious to see.”

“And what is that?” questioned Martin.

“The place where you grind up the money,” was the quick reply.

No great length of time was required for the two men to come to an understanding and the visitor left unceremoniously. The inexplicable feature of the whole circumstance is found In the fact that any banker should be so Ignorant of the practices of the Treasury Department as to suppose that uncancellcd currency would be allowed to leave the Institution In such an informal manner to he destroyed by unofficial hands.

Waldon Fawcett, Billions in His Trade, The Savannah Morning News, Savannah, Ga., July 21, 1901, Page 12. (PDF)