FEBRUARY 22 is near at hand, which means that we shall soon be honoring again the memory of George Washington. As usual, a part of the annual Washington Birthday celebration will consist of tributes to his greatness as a soldier and a statesman, as the leader in the American struggle for liberty and as the first President of the new nation. It is certain, too, that there will be a repetition of many of the familiar stories about “Washington, the man” and “Washington, the human being” and it is inevitable that, in retelling those stories, fact and fancy will be mixed, myth and legend will be recited once more and the “real Washington”—the Washington which you and I and our friends and associates in everyday life can understand—will still elude us.

Why is it that George Washington seems destined always to be a remote, shadowy figure in our minds? Why must he remain a god like personality aloof from humankind, a marble statue of a man who never once steps down from his pedestal to walk the earth like other men? One of the reasons is that the myth-makers went to work early in the history of our nation and one in particular seized upon George Washington as the subject for fashioning legendary tales. His name was Mason Locke Weems and he, more than any other man, is responsible for what millions of Americans think they know about George Washington.

So it seems appropriate to tell at this time the story of “Parson” Weems and his career. And not the least of the interest in that story is the fact that he himself is almost as shadowy a figure in the minds of most Americans as is the Washington which he helped create for them.

On October 1, 1759 a son was born to David Weems, a farmer in Anne Arundel county in the Province of Maryland, and his wife, Hester Hill Weems. Evidently there was no danger of “race suicide” in the Weems family for this was their 19th child! The boy was given the name of Mason Locke Weems and when he grew up was sent to Kent County school, at Chestertown.

At the age of fourteen young Weems went to England to study medicine and follow in the footsteps of a great uncle, Dr. William Locke, for whom he had been named. After graduating from the University of Edinburgh young Weems served for a time as a surgeon on a British warship. Then in 1776 he returned to America.

Apparently Weems took no part in the fight for liberty and during the last part of the war he seems to have had some association with Rev. William Smith, an energetic churchman who had taken over Weems’ alma mater, Kent County college, and was developing it into the present Washington college. Out of that association grew Weems’ decision to become a minister. After some difficulty in overcoming the prejudice of high Episcopal church officials in England against citizens of a “rebel colony,” Weems was finally ordained in 1784 and for the next five years served as rector of All Hallows church in Maryland.

During this time his income was meager and he eked it out by conducting a school for girls. Also during this time he was having other difficulties. He found himself unpopular with the conservative members of the parish because he was too willing to preach, if requested, to Methodists who had recently split off from the established church; too willing to exhort in ballrooms and other “ungodly” places; and too charitable in extending religious instruction to negroes—among them his own slaves whom he had freed several years before.

He Leaves the Ministry.

In 1790 Weems was without a charge and during the next two years he presided occasionally over the neighboring parish of Westminster. Finally, feeling that he was a failure as a minister, he decided to turn his talents to other work. During his service as a preacher he was a strong advocate of temperance and showed other signs of becoming a reformer. In that character he reprinted from the English original a popular medical pamphlet, the nature of which gave it a wide sale but scandalized some of the conservative churchmen. This not only hastened his decision to leave the ministry but pointed the way to another career—that of becoming a publisher and bookseller.

Back in 1784 an Irishman named Mathew Carey had come to Philadelphia and established a newspaper, to which venture he soon added the publication of books and magazines. In 1793 Weems met Carey and formed a business association with him which continued for more than three decades.

So “Parson” Weems became an itinerant bookseller and soon his travels were taking him all along the Atlantic seaboard. Moreover, he was making more money in this business than he had ever made before. So in 1795, when he married Fanny Ewall, the daughter of Col. Jesse Ewall, a prosperous planter near the Potomac river port of Dumfries, Va., he was able to install her in a comfortable home which he had bought in Dumfries. After the death of his father-in-law, Weems and his wife moved into Bel-Air, the Ewall mansion, and there he made his home, what time he was not out on his book peddling trips.

Important to this story are the facts that the Ewalls were closely related to the Balls, the family of George Washington's mother, that Colonel Ewall's sister married Dr. Craik, Washington's personal physician, and that Washington himself occasionally visited Colonel Ewall at Bel Air which was only 18 miles from Mount Vernon. But more important still is the fact that from a seller of books Weems' ambition led him to become a writer of books—or, more accurately, of pamphlets.

Washington's Indorsement.

His first venture in that field was taken about a year after his marriage. He collected a symposium of the utterances of Benjamin Franklin and other exponents of the homely virtues of life, which he published under the title of “The Immortal Mentor, or Man's Unerring Guide to a Healthy, Wealthy and Happy Life.” Washington, because of his friendship for the Ewall family, wrote an indorsement of the book. More than that, he permitted Weems to display this indorsement on the title page of the pamphlet and the magic of approval by the “Father of His Country” had much to do with the successful sale of Weems' little book.

When Washington retired from the Presidency Weems put out another book. It was called “The Philanthropist: or a Good Twenty-Five Cents worth of Political Love Powder for Honest Adamsites and Jeffersonites” and it was a protest against the partisan political spirit which was dividing the country. Along with Weems' plea for harmony among the citizens of the country in this book were sketches of the nation's fighting men during the revolution, designed to stir up patriotic sentiments in his readers.

Because of the double purpose of this book Washington indorsed it also, with these words: 'Much indeed is it to be wished that the sentiments contained in your pamphlets, and the doctrine it endeavors to inculcate, were more prevalent—Happy would it be for this country at least, if they were so.”

This was in August, 1799. With in four months Washington lay dead at Mount Vernon. In January, 1800, Weems wrote to his friend and business associate, Carey, as follows:

I've something to whisper in your lug. Washington, you know, is gone! Millions are gaping to read something about him. I am very nearly prim'd and cock'd for 'em.

So within a few months there appeared an 80-page pamphlet bearing the title of “A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington; dedicated to Mrs. Washington, by the Rev. M. L. Weems of Dumfries.” Its author was quite correct in believing that “millions are gaping to read something about him.” For the first edition of the pamphlet was soon sold out and a second edition followed quickly. In this edition the author added a line to the title “Faithfully taken from authentic documents” probably because some skeptic had questioned some of his statements.

The Book Grows.

But the public seemed willing to accept what he had written about the great Washington unquestioningly. The book was selling so fast that it was difficult to keep up with the demand for it. A new edition appeared every year and each successive edition was larger than the previous one. By the time the fifth edition was published in 1806 the 80 pages had grown to 250 and its title now read “The Life of George Washington, with curious anecdotes,

(Picture used as the frontispiece in Weems' biography.)

equally honorable to himself and exemplary to his young country men.” Also the author now described himself on the title-page as the “former rector of Mt. Vernon parish,” despite the fact that there was no Mount Vernon parish in Virginia, any more than he was, as he described himself in later editions, “former rector of General Washington's parish.”

The buyers of Weems' book, however, apparently weren't concerned about the accuracy of the author's description of himself anymore than they were concerned about the accuracy of some of his “curious anecdotes.” They literally “swallowed them whole;” they told them to their children, who in turn told these tales to theirs. Thus did some of the legends about George Washington become deeply-rooted in American belief.

Chief among these legends is the familiar cherry-tree story. Weems declared that this story was told to him by “an aged lady connected with the household of the elder Washington” but he took care never to tell her name. The same anonymous “lady” is also the authority for the story of how Wahington's father tried to “startle George into a lively sense of his Maker.” This story, while not so well known as the cherry tree story, is equally interesting. In it Weems has the elder Washington tracing George's name in the earth in his garden-patch and planting it with cabbage seed. A little later the boy is shown what is apparently a miracle—his name, “George Washington,” spelled out in green shoots coming up from the ground. When young George runs to his father for an explanation, the parent makes his little trick an excuse for a sermon on the workings of Omniscience.

The Origins of His Tales.

If there was ever the slightest bit of evidence to support either story historians, who presumably have dug up every possible bit of information that has a bearing on Washington's early life, have never been able to discover it. What they have discovered, however, is this:

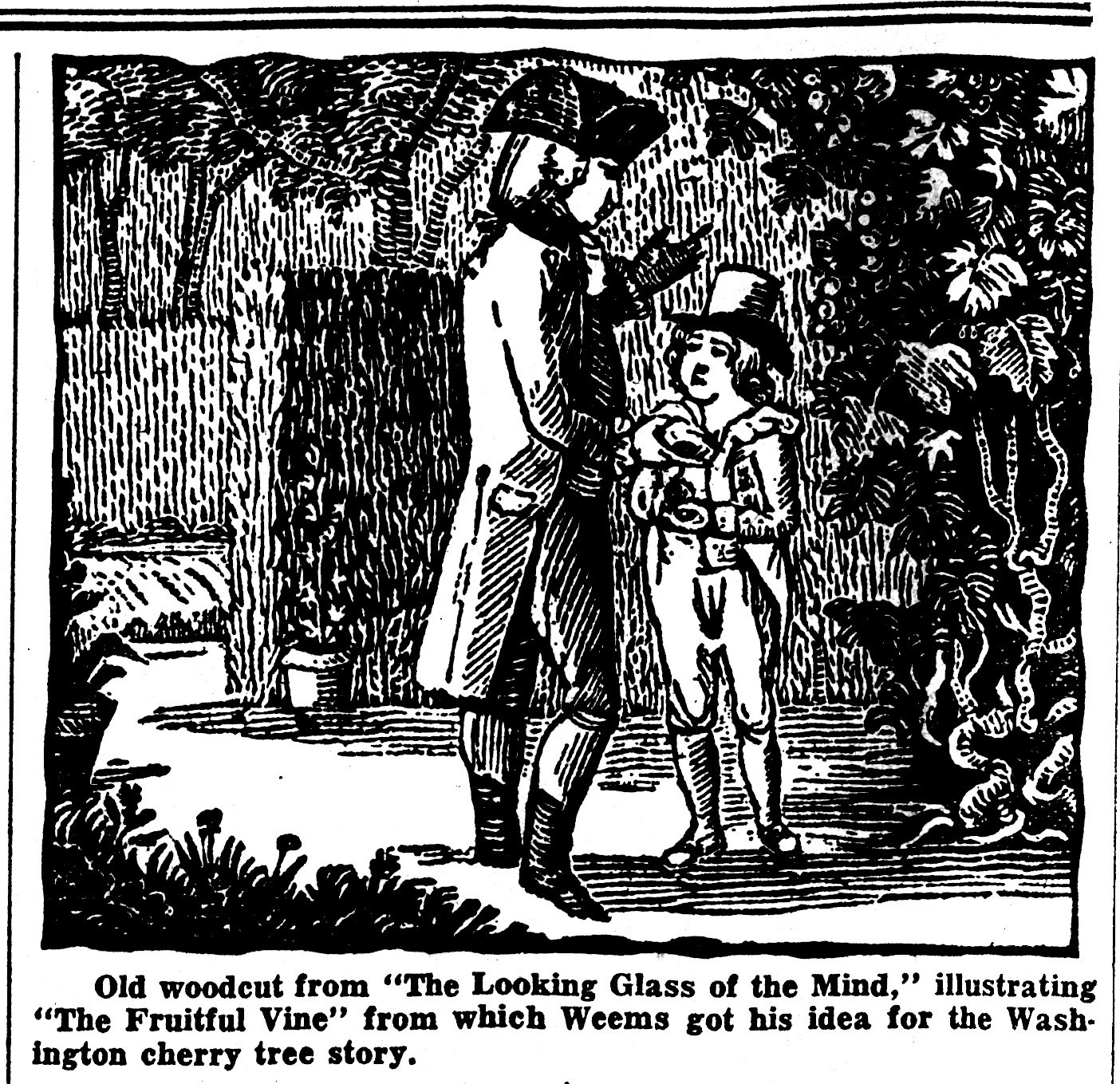

Back in 1797 John Bioren of Philadelphia published a book called “The Looking Glass for the Mind; or, the Juvenile Friend.” Later editions of this same book were brought out by T. B. Jansen and Company of New York. In them appeared a story called “The Fruitful Vine,” in which a father moralizes to his son much as the elder Washington moralizes to young George in the cherry tree story. Since the cherry tree story did not appear in the earlier editions of Weems' biography but in later ones (after the publication of “The Looking Glass for the Mind”) scholars are convinced that the “Parson” based his cherry tree story on the vine story. Similarly, an anecdote, invented by an English squire long before Washington's time to impress his son with the greatness of God, gave Weems the idea for his cabbage seed story.

“The Fruitful Vine” from which Weems got his idea for

the Washington cherry tree story.

Although the origin of some of the other stories which Weems included in his book are not so easily detected, there is little doubt in the minds of historians that they are pure inventions by the “Parson” with only the slightest, if indeed any at all, foundation in fact. All of them, of course, were highly moral and all tended to paint the youthful Washington as nearly perfect as a boy could be.

About a decade ago Washington's biographer was himself the subject of a biography. It was “Parson Weems of the Cherry Tree,” written by Harold Kellock and published by the Century company. In this book Kellock, commenting upon the fact that Weems originated so many Washington legends, says:

“He (Washington) was first in manly games, the fastest runner, the best jumper, and could throw farthest. In fact, this young Admirable Crichton was the hero of a literary artist who knew the commercial value of laying on virtue with the heavy trowel. In these and other fables of a similar character scattered through the book, Weems created a Washington that all the study and research of the scholars have been unable to erase. It is the Weemsian Washington that persists in the school readers and in the popular imagination, a figure of truly terrifying piosities and incredible perfections, and, as Mr. Albert J. Beveridge remarks in his life of John Marshall, ‘an impossible and intolerable prig.’”

An Early Best Seller

Be that as it may, the American people of the Nineteenth century evidently wanted their heroes pious to the point of priggishness for they accepted “Parson Weems portrait of Washington as an authentic one and handed it down to us.

Before Weems' death in 1825 he wrote many other books, most of them moral tracts such as “The Drunkard's Lookingglass,” “God's Revenge Against Murder,” “God's Revenge Against Gambling” etc. Undoubtedly they were popular in their day but that day soon passed. More enduring was his masterpiece even though it was a master piece of mixed fiction and fact. For his “Life of Washington”—that paradox of a book filled with untruths about a man whom he painted as the paragon of truthfulness!—is more than an early “best seller,” It is a monument to a master myth-maker who gave a nation legend and convinced them that it was History.

© Western Newspaper Union.