The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

March 21, 1934

Slave Girl Sold to Brooklyn Bidders At Sensational Plymouth Church Auction

Henry Ward Beecher Raised Over $1,000 to Free 'Pinky' at Time of Auction in 1860 and in 1927 Her in Abolitionist Rally at Historic Borough Church

By Guy Hickok

A slave girl was sold at auction in Orange St, on the Heights. This dramatization here in the North —in Plymouth Church— of the selling of a human to the highest bidder, created a sensation throughout the nation.

Henry Ward Beecher Brooklyn’s leading citizen and the auctioneer, already a noted abolitionist, became a nationally controversial figure. A famous Weekly attacking him published a full-page cartoon showing Beecher refusing communion to George Washington on the ground that Washington had been a slave owner. "Friends or the South" in New York denounced Beecher for arousing abolitionist feeling.

Plymouth Church under his pastorate had become one or the "sights" of New York. Hundreds of transients from New York hotels came every Sunday to hear Beecher preach. For they knew that when they went home to Pennsylvania, Ohio or Indiana their friends would ask "Did you hear Beecher?" as today would ask. "Did go up in the Empire State Building?"

This was in the Winter of 1860. Yet though Beecher’s fame was widespread the record of his eloquence at that period is astonishingly scant. It was not until after the Civil War that stenographer was found who could take his sermons in short-hand.

Crowd Awaited Thrill

On Sunday, Feb. 5, 1860, Plymouth was as usual crammed, with the late arrivals standing in the doorways, and with a favored few of those unable to find seats in pews crouched on the steps of the altar or seated facing the audience on its edge. The proportion of men to women was about five to one, though the latter were sufficiently numerous to produce a perceptible rustling of stiff taffetas as they settled their wide skirts and waited for the thrill to come. What the thrill would be they did not know. For "advance publicity" was still to be invented.

Mr. Beecher entered the church leading a little girl by the hand. He threaded his way through the crowd about the altar, stepped carefully between those on the steps, patted the heads of two of the boys perched on the ledge, ushered the little girl to a chair, threw his soft felt hat under a small table, seated himself, crossed his legs, took off his rubbers and settled himself for the evening service.

Fair Plainly Dressed Girl

The little girl sat with her eyes cast down, moving nervously. Those who looked at her saw a fair little girl, her hair a little wavy to be true, but with nothing about her except unusual plainness of dress to distinguish her from little girls they had left at home.

Could it be? Mr. Beecher had created a sensation as long ago as 1848, a year after he had come from "the far West" (then Indianapolis) by auctioning off a slave girl in the Broadway Tabernacle across the river. A few in the audience remembered and wondered, but most waited, with no notion of what was coming.

When the hymns had been sung and the prayer pronounced Beecher arose. He was a short man. He described himself as a "sawed-off"; but there was drama in his slightest gesture.

Today he would be described as superb actor, but in 1860 that description would have been neither respectful nor respectable.

He began very simply by explaining that, the little girl "Pinky" had been brought from Washington, D. C. by the Rev. Bishop Faulkner, prominent member of the congregation, after great trouble. Her master had agreed to "sell her to freedom." But he had placed upon her a value of $900 and had made some trouble about a bond.

'An Underground Station'

Several substantial Washington abolitionists had signed their names>

to the bond guaranteeing that either the $900 would be forthcoming or "Pinky" would returned. Then the owner had been seized with doubt. Plymouth Church had a bad name in the South. It was known as an important station on the Underground Railway, and by some was called its Grand Central Depot. Most of its congregation were known as "stockholders" in the line.

"Pinky’s' owner very nearly decided not let her be taken to a place of such repute, fearing a swindle. But the bondsmen finally convinced him that he could not lose.

During this narration, calmly made. "Pinky" had grown more and more nervous as attention was concentrated upon her, and suspense had risen in the congregation to an uncommon pitch. They knew that Beecher was working to an emotional climax. But when would it come?

Turning toward "Pinky" with a sweeping gesture, Beecher raised his voice.

'Marketable Commodity'

"And this," he said in full tones, "is a marketable commodity. Such as she is, I put her into one balance, with silver in the other."

He explained that "Pinky's" grandmother had bought her own freedom and had striven for years to obtain enough money to buy that of the child. But slaves were valuable. As an old slave near her end,the grandmother had found herself much cheaper than her granddaughter, who had a lifetime of potential labor before her.

Then, as he had done once before, Beecher impersonated a Charleston slave auctioneer. A marvelous mimic, he dramatized in Orange St. the sale Of human beings as cattle. He described the physical, mental and moral qualities of the girl, praising all highly.

"And more than that, gentlemen." he shouted in the accent of the Southern auctioneer, "they say she is of a family of praying Methodist Niggers. Who bids? … A thousand … fifteen hundred … two thousand … Going … Going … Last Call … Gone." Little Pinky was so aroused that she could scarcely contain herself. She began to weep softly, probably not knowing exactly why.

Asks for $900

Dropping the impersonation. Beecher asked those prescnt to give as the offering the $900 needed to buy "Pinky" away from life as a chattel.

"Of all the meetings I ever attended, for a panic of sympathy I never saw one surpassing that," wrote many years later one witness of the scene. And Beecher himself wrote of it: "Rain never fell faster than the tears fell then."

The collection plates were rapidly filled, but many in the congregation had come unprepared for such an offering and stripped off rings and jewelry. In one of the plates Mr. Beecher saw a ring, a large fire opal. He took it in his hand and, with his sure instinct for the dramatic, lifted "Pinky's" hand, wet with her own tears, placed the ring on her finger and, with a gesture of blessing, said:

'Wed to Freedom'

"With this ring I do wed thee to freedom." It was a ring tossed in the plate by Rose Terry, a Brooklyn woman, who had come to church that day without her purse. She said later had it been the Orioff diamond she would have done the same, so powerful had been the appeal of the spectacle.

More than a thousand dollars was collected. The service was concluded with the usual ritual of song and benediction and the congregation streamed out of the church still under the spell of great emotion.

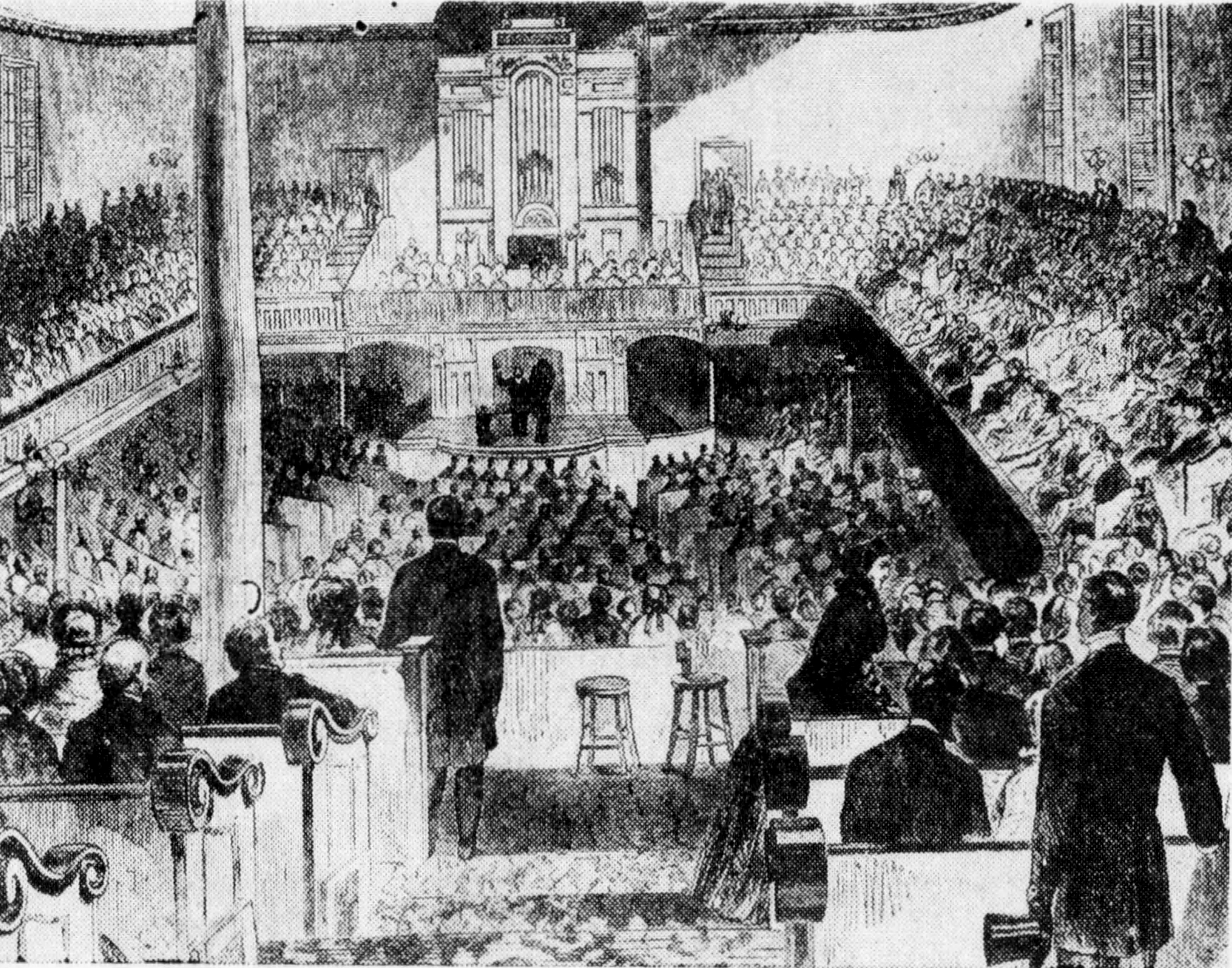

Below — Interior of Plymouth Church during services shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War.

"Pinky" stayed with the Beechers for a few days, marveling at her "freedom ring." And a visitor to the house, Eastman Johnson, the painter seeing her sitting on the floor staring at the symbol she did not quite understand, brought his canvas and reproduced the scene.

Lincoln Interest In Story

"Pinky" afterward called herself Rose Ward Diggs for the giver of the ring and the great clergyman who had made her free. She wrote a small book telling of her experiences and with the money from its sale and funds contributed by the church attended Howard University.

Mr. Beecher saw her four years later in the home of Chief Justice Chase in Washington. President Lincoln was much interested in her story as Beecher told it.

Later for many years "Pinky" dropped from sight.

She came back to Plymouth for a day on May 15, 1927, a woman of 77, and was welcomed again to the platform on which her freedom had been given.