The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Sunday, May 15, 1927

Aged Negro's ‘Tip’ Led to Dr. Durkee's Discovery of Mrs. Hunt, Famous Slave Girl ‘Pinky.’ Sold by Henry Ward Beecher.

Informal Chat Between Former President of Howard University and Colored Friend Made Known Identity of Girl Whose Auction in Church Became World Renowned.

It was at the close of a busy day's Work, about a year ago, that an aged negro was ushered into the office of Dr. J. Stanley Durkee, president of Howard University for colored students at Washington.

Dr. Durkee had just that week accepted the call to come to historic Old Plymouth Church as its fourth pastor. He had lots of work to finish up at the school before assuming his new task as pastor of perhaps the most famous church in the country. But Dr. Durkee is a genial soul and always has time for an old friend.

The two chatted while, the white minister-president and the elderly negro. They mentioned Dr. Durkee's leaving the college after his many years of pleasant association there.

“But it will be nice to get back to real church work again, especially Plymouth Church, with its history and traditions.” reflected the president.

Negro Gives “Tip.”

“I know the woman who was the original slave girl sold by Henry Ward Beecher at Plymouth Church,” casually remarked the elderly negro.

And that is how Dr. Durkee “happened to run across” Mrs. James Hunt, wife of a negro lawyer in Washington, and the woman who was “Pinky.” the slave child auctioned from Beecher's pulpit in 1860 as a protest against slavery.

Dr. Durkee lost no time in looking up Mrs. Hunt at her home, 411 Florida ave., Washington, and he learned she had been a student at Howard University Normal School 50 years ago. From the records he was able to trace her identity and remove any shadow of doubt that she is the real “Pinky.”

Has Lived Obscurely.

Mrs. Hunt has lived a life of comparative obscurity since that exciting day in Plymouth Church when she was sold to win her freedom.

When Dr. Durkee was planning his program for the 80th anniversary of Henry Ward Beecher's first sermon next Sunday he thought it would be interesting to mention the slave girl. He wrote to her in Washington and invited her to attend the services. Readily she accepted because of Dr. Durkee's work among her people.

The Plymouth pastor has described Mrs. Hunt as a “modest, retiring, quiet and cultured woman.” She is 76 but does not look it. Her husband is a negro lawyer of note. She has three children and several grandchildren.

Church Auction World Famous.

When Henry Ward Beecher turned his pulpit into an auction block he became a national figure. He was writing American history. Never before nor since has anything so spectacular taken place in a church. The appearance of “Pinky” in Dr. Durkee's pulpit as part of Plymouth Church's 80th anniversary celebration, closely approaches the sensation of 1860. It is the first time the slave child —now an old woman— has been back to the scene where she gained her freedom from slavery 67 years ago.

No incident in Mrs. Hunt's life since has equaled that dramatic moment when Mr. Beecher sold her freedom. The 9-year-old mulatto girl, named Sally Maria Diggs but nicknamed “Pinky,” was brought to Brooklyn by her grandmother, an enterprising woman who had purchased her own freedom.

Sold First When 7.

“Pinky” was born a slave an Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, of a white father and a negro slave girl. When she was 7 her mother and two brothers were sold to a slave trader in Alexandria, Va., and she lost trace of them forever. A short time later “Pinky.” with five little cousins and her grandmother was sold in Baltimore. The grandmother bought her own freedom and took “Pinky” with her to Brooklyn, she had heard Henry Ward Beecher was preaching against slavery. She Interested the Brooklyn minister in the child and he suggested selling her from his pulpit.

The auction was a mere formality. It was a protest against slavery, and the most effective he could use. The fashionable Plymouth congregation was so moved at the sight of this little slave child, almost white, that they subscribed more than the necessary $900 for her sale —which in reality liberated her. She was taken into the family of a brother of John Falkner Blake and educated here.

Taken to Washington.

The old grandmother did not like the North, however, and returned to Washington, taking the free “Pinky&rduo; with her. There she went to college and eventually taught school.

There are two versions of how “Pinky” got her nickname. One is said to be the result of Henry Ward Beecher's christening her Rose Ward.

During the auction Rose Terry, the authoress, was in the congregation. She was so moved by Mr. Beecher's sermon she took a ring from her finger and tossed it on the altar. Mr. Beecher picked it up and placed it on the slave child's finger, saying: “With this ring, I thee wed to freedom.” and he called her Rose Ward, after the authoress and his own middle name.

Someone in the congregation suggested she be called Beecher, but the great minister refused on the ground that it would make the child too conspicuous throughout her life. From Rose it is said the little girl's nickname became “Pinky.”

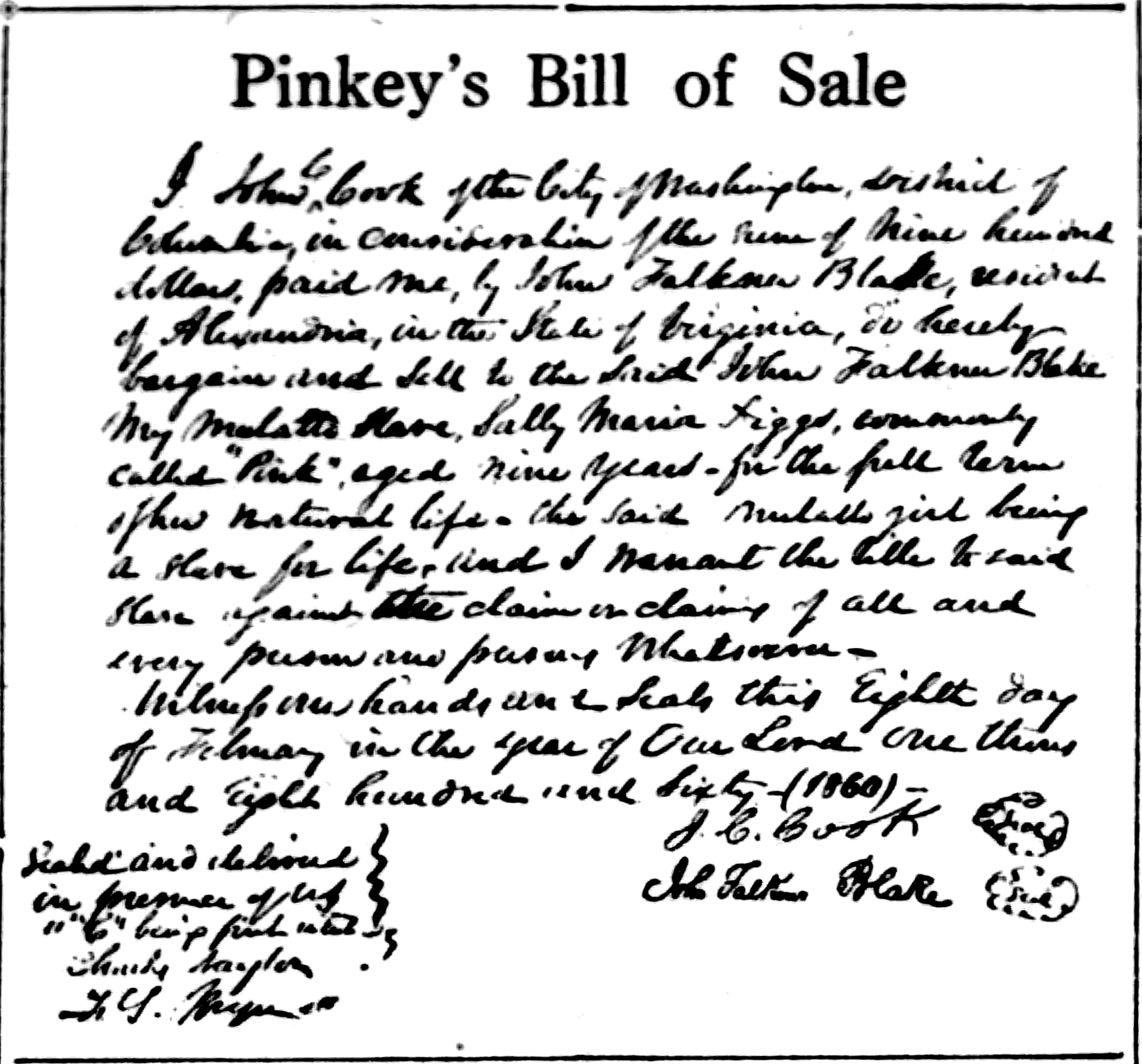

Called “Pink” in Bill of sale.

This, however, is perhaps more pretty than exactly a fact. For in the “bill of sale.” signed by John C. Cook of Washington. D. C., there is written “my mulatto slave, Sally Maria Diggs, commonly called ‘Pink,’ aged 9 years.”

The other version is to the effect that the pretty little mulatto child won her nickname from her soft pink cheecks.

In 1910 the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the purchase of the slave child was held at Plymouth Church. At that time the late Gen. Horatio King presented to the Rev. Dr. Newell Dwight Hillis, then pastor, a photograph of the famous painting of “Pink,” by Eastman Johnson.

The original painting by the artist had been given to Henry Ward Beecher but was later purchased by an art lover. The painting represents “Pinky,” a beautiful mulatto sitting on the floor of an attic symbolic of the fact that “Pinky” when first sold as a slave by her master ran upstairs to the attic and refused to go to her owner. She was later taken by her grandmother to Brooklyn and sold by Beecher.

The day Henry Ward Beecher sold “Pinky” was recalled in 1910 by the late Senator Stephen Griswold. who at that time was the last surviving member of the congregation present at the auction. He said then:

Women Gave Rings.

“I remember well the appearance of the girl, She was about 9 years old. She stood by the side of Mr. Beecher, looking out on the vast congregation with her large dark eyes. Hardly a sound came from the people. I was one of the ushers and I took a basket and passed it along the north balcony. The baskets were rapidly filled. Women took rings from their fingers.”

When the money in the baskets had been counted Mr. Beecher announced solemnly that $1,500 was collected. The jewels were returned, with the exception of Miss Terry's gold ring. The sale price of “Pinky” was $900.

At the time the slave market quoted $1,500 to $1,800 for a young man in the prime of life. A young woman able to work was sold for about $1,200. Children who were healthy usually brought about $600 on the auction block. Octoroon children were worth slightly more than all black. One of the worst features about the slave market was the sale of young octoroon women, particularly if they were beautiful, for immoral purposes.

“Pinky” was not the only slave sold from Beecher's pulpit, although her case attracted widespread public attention because she was so young and beautiful.

In June, 1856, he sold a 20-year-old girl called Sarah for $1,200. She was a handsome slave, almost pure white, with long straight black hair. When Beecher was auctioning her off for her freedom her hair tumbled down and fell below her waist.

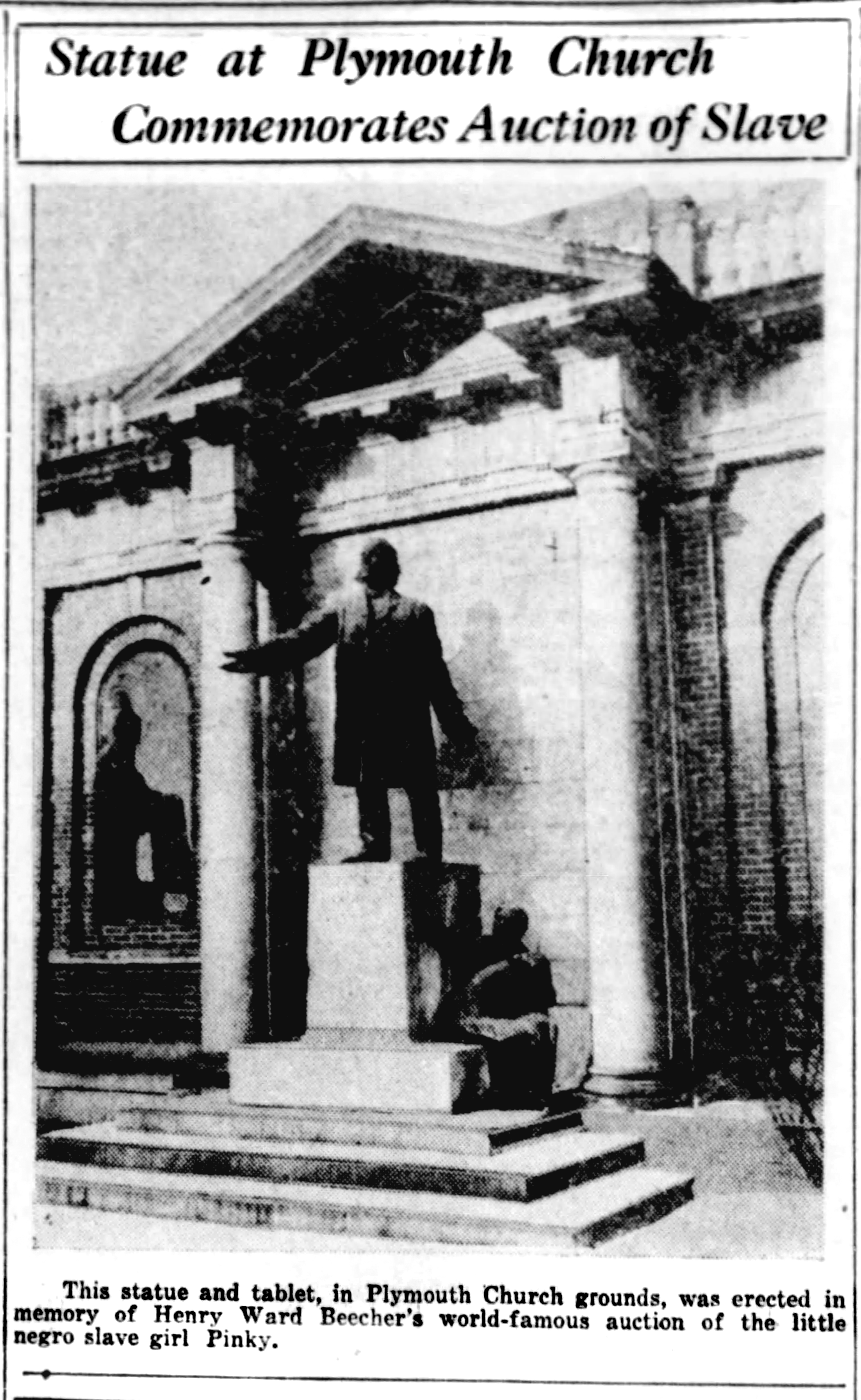

Statue at Plymouth Church Commemorates Auction of Slave

This statue and tablet, in Plymouth Church grounds, was erected in memory of Henry Ward Beecher's world-famous auction of the little negro slave girl Pinky.