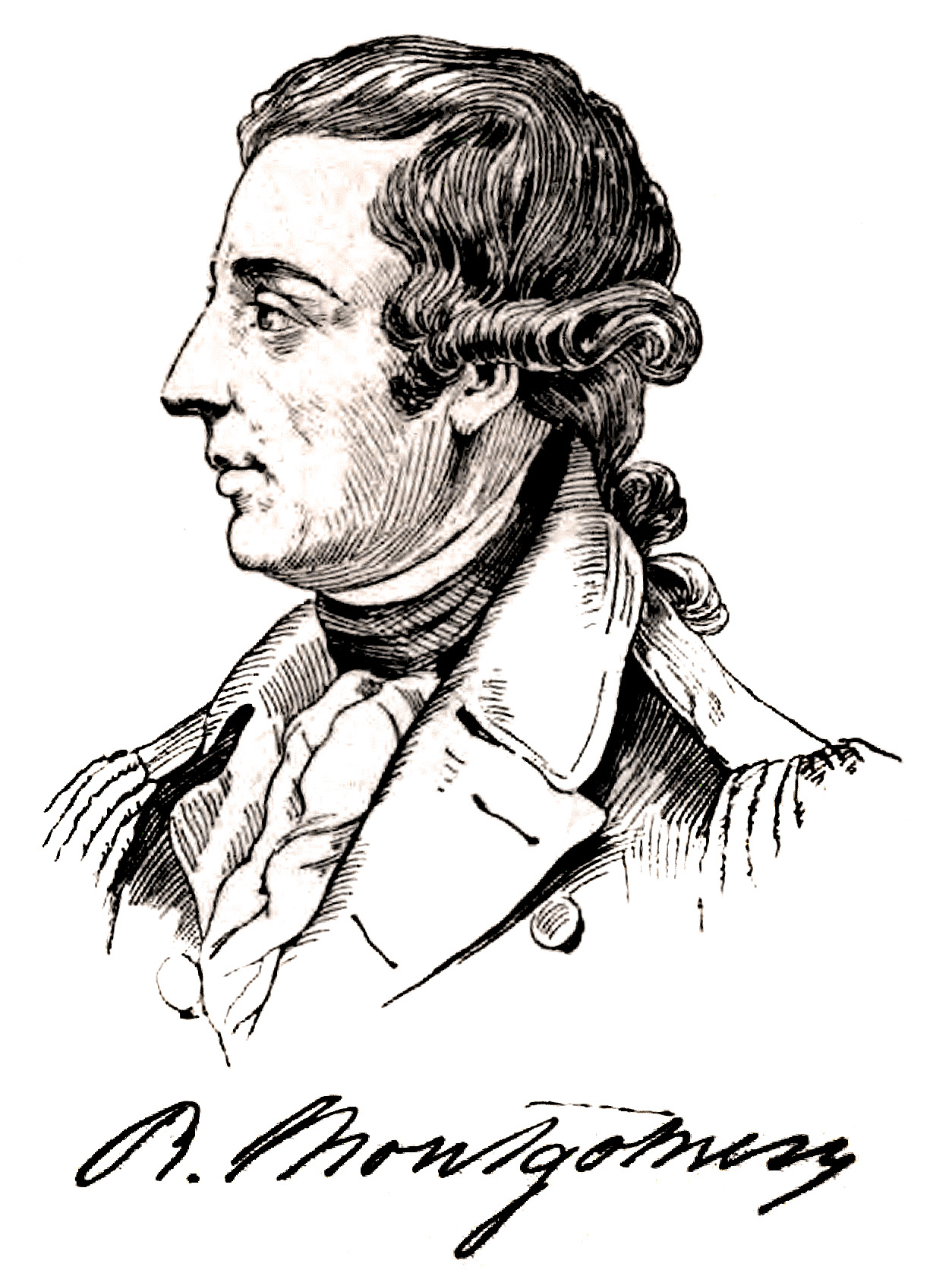

MONTGOMERY, Richard, soldier, b. in Swords, near Feltrim, Ireland, 2 Dec, 1736; d. in Quebec, Canada, 31 Dec. 1775. He was the son of Thomas Montgomery, a member of the British parliament for Lifford, and was educated at Trinity college, Dublin.

He entered the English army at the age of eighteen as an ensign in the 17th infantry, and in 1757 was ordered to Halifax, N. S. Soon after he participated in the siege of Louisburg under James Wolfe, where he was promoted lieutenant, also taking part in the expedition that was sent under Sir Jeffrey Amherst in 1759 to reduce the French forts on Lake Champlain. In 1760 he became adjutant of his regiment and served in the army that marched on Montreal under Col. William Haviland, becoming captain in 1762. He was then ordered to the West Indies, and fought in the campaigns against Martinique and Havana. In 1763 he returned to New York, after which he spent some time in Great Britain, where he became intimate with many of the liberal members of parliament, numbering among his friends Isaac Barre, Edmund Burke, and Charles James Fox. His claims for advancement being neglected, he sold his commission in 1772 and returned to this country early in 1773, purchasing a farm of sixty-seven acres at King's Bridge (now part of New York city), where soon afterward he married Janet, daughter of Judge Robert R Livingston {q.v.}. He purchased a handsome estate on the banks of Hudson river, but spent the few years of his married life in his wife's residence of Grassmere, near Rhinebeck. In May, 1775, he was sent as a delegate to the 1st Provincial congress in New York city, and in June of the same year was made a brigadier-general in the Continental army, the second on the list of the eight that were appointed, and the only one not from New England. It is said that of the three from those who had been officers in the British army “Montgomery, though perhaps inferior to Charles Lee in quickness of mind, was much superior to both him and Gates in all the great qualities which adorn the soldier.” He was designated to serve as second in command under Gen. Philip Schuyler on the expedition to Canada, but, through the illness of the superior officer, the entire command devolved upon Montgomery. Proceeding by way of the Sorel river, and notwithstanding the mutinous conduct of his soldiers, the lack of proper munitions, and incidental suffering, he made the brilliant campaign that resulted in the reduction of the fortresses of St. John's (where the colors of the 7th fusileers were captured, being the first taken in the Revolutionary war), and Chambly and the capture of Montreal during the latter part of 1775. He then wrote to congress: “Till Quebec is taken Canada is unconquered.” His little army of scarcely 300 men joined that of Benedict Arnold, consisting of about 600 men, before Quebec early in December, and for his past services Montgomery was made major-general on 9 Dec. The term of enlistment of his men was about to expire, the small-pox was prevalent in the camp, and, with the winter before them, a prolonged siege was impossible, and therefore the immediate capture of Quebec became a necessity. Montgomery called a council of war, at which it was decided to carry the city by assault, and to him was intrusted the advance on the southern part of the lower town. The attack was made early in the morning of 31 Dec, 1775, during a heavy snow-storm, Montgomery himself leading his men from Wolfe's Cove, along the side of the cliff beneath Cape Diamond, to a point where a fortified block-house stood protected in front by a stockade. The first barrier was soon carried, and Montgomery, exclaiming, “Men of New York, you will not fear to follow where your general leads,” pushed onward, when with his two aides he was killed by the first and only discharge of the British artillery. His soldiers, discouraged by his fall, retreated, and the enemy, able to concentrate their attention on the forces under Col. Arnold, soon drove the Americans from the city, besides capturing about 400 of his men. Enemies and friends paid tribute to Montgomery's valor. The governor, lieutenant-governor, and council of Quebec, and all the principal officers of the garrison, buried him with the honors of war. At the news of his death “the city of Philadelphia was in tears; every person seemed to have lost his nearest friend.” Congress proclaimed for him “their grateful remembrance, respect, and high veneration; and desiring to transmit to future ages a truly worthy example of patriotism, conduct, boldness of enterprise, insuperable perseverance, and contempt of danger and death,” they reared a marble monument in the front of St. Paul's church. New York city, in honor of the patriotic conduct, enterprise, and perseverance of Maj.-Gen. Richard Montgomery.” In the British parliament, Edmund Burke contrasted the condition of the 8,000 men, starved, disgraced, and shut up within the single town of Boston, with the movements of the hero who in one campaign had conquered two thirds of Canada. To which Lord North replied: “I cannot join in lamenting the death of Montgomery as a public loss. Curse on his virtues! they've undone his country. He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous; but: still he was only a brave, able, humane, and generous rebel.” “The term of rebel,” retorted Fox, “is no certain mark of disgrace. The great asserters of liberty, the saviors of their country, the benefactors of mankind in all ages, have been called rebels.” High on the rocks over Cape Diamond, along which this brave officer led his troops on that fatal winter morning, has been placed the inscription: “Here Major-General Montgomery fell, December 31st, 1775.” He is described, when he was about to start from Saratoga on his Canadian campaign, “as tall, of fine military presence, of graceful address, with a bright, magnetic face, winning manners, and the bearing of a prince”;

He entered the English army at the age of eighteen as an ensign in the 17th infantry, and in 1757 was ordered to Halifax, N. S. Soon after he participated in the siege of Louisburg under James Wolfe, where he was promoted lieutenant, also taking part in the expedition that was sent under Sir Jeffrey Amherst in 1759 to reduce the French forts on Lake Champlain. In 1760 he became adjutant of his regiment and served in the army that marched on Montreal under Col. William Haviland, becoming captain in 1762. He was then ordered to the West Indies, and fought in the campaigns against Martinique and Havana. In 1763 he returned to New York, after which he spent some time in Great Britain, where he became intimate with many of the liberal members of parliament, numbering among his friends Isaac Barre, Edmund Burke, and Charles James Fox. His claims for advancement being neglected, he sold his commission in 1772 and returned to this country early in 1773, purchasing a farm of sixty-seven acres at King's Bridge (now part of New York city), where soon afterward he married Janet, daughter of Judge Robert R Livingston {q.v.}. He purchased a handsome estate on the banks of Hudson river, but spent the few years of his married life in his wife's residence of Grassmere, near Rhinebeck. In May, 1775, he was sent as a delegate to the 1st Provincial congress in New York city, and in June of the same year was made a brigadier-general in the Continental army, the second on the list of the eight that were appointed, and the only one not from New England. It is said that of the three from those who had been officers in the British army “Montgomery, though perhaps inferior to Charles Lee in quickness of mind, was much superior to both him and Gates in all the great qualities which adorn the soldier.” He was designated to serve as second in command under Gen. Philip Schuyler on the expedition to Canada, but, through the illness of the superior officer, the entire command devolved upon Montgomery. Proceeding by way of the Sorel river, and notwithstanding the mutinous conduct of his soldiers, the lack of proper munitions, and incidental suffering, he made the brilliant campaign that resulted in the reduction of the fortresses of St. John's (where the colors of the 7th fusileers were captured, being the first taken in the Revolutionary war), and Chambly and the capture of Montreal during the latter part of 1775. He then wrote to congress: “Till Quebec is taken Canada is unconquered.” His little army of scarcely 300 men joined that of Benedict Arnold, consisting of about 600 men, before Quebec early in December, and for his past services Montgomery was made major-general on 9 Dec. The term of enlistment of his men was about to expire, the small-pox was prevalent in the camp, and, with the winter before them, a prolonged siege was impossible, and therefore the immediate capture of Quebec became a necessity. Montgomery called a council of war, at which it was decided to carry the city by assault, and to him was intrusted the advance on the southern part of the lower town. The attack was made early in the morning of 31 Dec, 1775, during a heavy snow-storm, Montgomery himself leading his men from Wolfe's Cove, along the side of the cliff beneath Cape Diamond, to a point where a fortified block-house stood protected in front by a stockade. The first barrier was soon carried, and Montgomery, exclaiming, “Men of New York, you will not fear to follow where your general leads,” pushed onward, when with his two aides he was killed by the first and only discharge of the British artillery. His soldiers, discouraged by his fall, retreated, and the enemy, able to concentrate their attention on the forces under Col. Arnold, soon drove the Americans from the city, besides capturing about 400 of his men. Enemies and friends paid tribute to Montgomery's valor. The governor, lieutenant-governor, and council of Quebec, and all the principal officers of the garrison, buried him with the honors of war. At the news of his death “the city of Philadelphia was in tears; every person seemed to have lost his nearest friend.” Congress proclaimed for him “their grateful remembrance, respect, and high veneration; and desiring to transmit to future ages a truly worthy example of patriotism, conduct, boldness of enterprise, insuperable perseverance, and contempt of danger and death,” they reared a marble monument in the front of St. Paul's church. New York city, in honor of the patriotic conduct, enterprise, and perseverance of Maj.-Gen. Richard Montgomery.” In the British parliament, Edmund Burke contrasted the condition of the 8,000 men, starved, disgraced, and shut up within the single town of Boston, with the movements of the hero who in one campaign had conquered two thirds of Canada. To which Lord North replied: “I cannot join in lamenting the death of Montgomery as a public loss. Curse on his virtues! they've undone his country. He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous; but: still he was only a brave, able, humane, and generous rebel.” “The term of rebel,” retorted Fox, “is no certain mark of disgrace. The great asserters of liberty, the saviors of their country, the benefactors of mankind in all ages, have been called rebels.” High on the rocks over Cape Diamond, along which this brave officer led his troops on that fatal winter morning, has been placed the inscription: “Here Major-General Montgomery fell, December 31st, 1775.” He is described, when he was about to start from Saratoga on his Canadian campaign, “as tall, of fine military presence, of graceful address, with a bright, magnetic face, winning manners, and the bearing of a prince”;  and it was here that he parted from his wife after her two brief years of happiness with her “soldier,” as she always afterward called him. Many of the letters that he wrote to her during the winter months of 1775 have been preserved, and in one of the last he writes: “I long to see you in your new home,” referring to Montgomery Place, a mansion that he had projected before his departure on the property purchased by him near Barrytown and that was completed during the following spring. In 1818, by an “Act of honor” passed by the New York legislature in behalf of Mrs. Montgomery, Sir John Sherbrooke, governor-general of Canada, was requested to allow her husband's remains to be disinterred and conveyed to New York. This being granted, De Witt Clinton, then governor of the state, appointed her nephew, Lewis, son of Edward Livingston, to take charge of the body while it was on its way. As the funeral cortege moved down the Hudson, nearing the home that he had left in the prime of life to fight for his adopted country, Mrs. Montgomery took her place on the broad veranda of the mansion (shown in the engraving) and requested that she might be left alone as the body passed. She was found unconscious stretched upon the floor, where she had fallen, overcome with emotion. Gen. Montgomery's remains found their last resting-place in St. Paul's chapel in New York city near the monument that was ordered in France by Benjamin Franklin. Mrs. Montgomery survived her husband for fifty-two years, and on her death in 1838 her house became the property of her youngest and only surviving brother, Edward Livingston {q. v.}. The mansion continued to be his residence until his death, and there his widow, Louise, spent the remaining twenty-five years of her life. See “Life of Richard Montgomery,” by John Armstrong, in Sparks's “American Biography” (Boston, 1834), and the “Ancestry of General Richard Montgomery,” by Thomas H. Montgomery, in the “New York Genealogical and Biographical Record” (July, 1871), where his relationship to the ancestral Scottish family is traced.

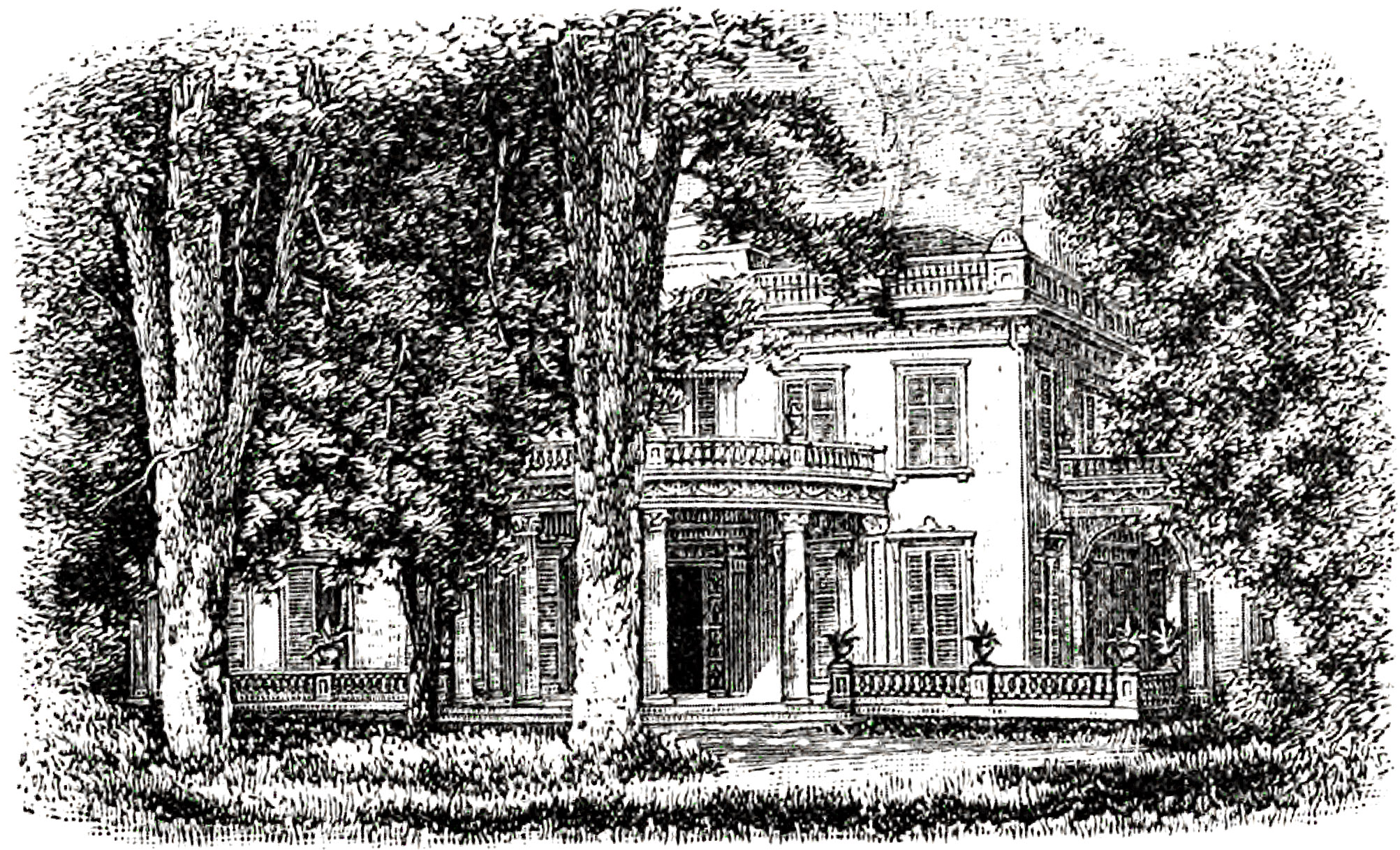

and it was here that he parted from his wife after her two brief years of happiness with her “soldier,” as she always afterward called him. Many of the letters that he wrote to her during the winter months of 1775 have been preserved, and in one of the last he writes: “I long to see you in your new home,” referring to Montgomery Place, a mansion that he had projected before his departure on the property purchased by him near Barrytown and that was completed during the following spring. In 1818, by an “Act of honor” passed by the New York legislature in behalf of Mrs. Montgomery, Sir John Sherbrooke, governor-general of Canada, was requested to allow her husband's remains to be disinterred and conveyed to New York. This being granted, De Witt Clinton, then governor of the state, appointed her nephew, Lewis, son of Edward Livingston, to take charge of the body while it was on its way. As the funeral cortege moved down the Hudson, nearing the home that he had left in the prime of life to fight for his adopted country, Mrs. Montgomery took her place on the broad veranda of the mansion (shown in the engraving) and requested that she might be left alone as the body passed. She was found unconscious stretched upon the floor, where she had fallen, overcome with emotion. Gen. Montgomery's remains found their last resting-place in St. Paul's chapel in New York city near the monument that was ordered in France by Benjamin Franklin. Mrs. Montgomery survived her husband for fifty-two years, and on her death in 1838 her house became the property of her youngest and only surviving brother, Edward Livingston {q. v.}. The mansion continued to be his residence until his death, and there his widow, Louise, spent the remaining twenty-five years of her life. See “Life of Richard Montgomery,” by John Armstrong, in Sparks's “American Biography” (Boston, 1834), and the “Ancestry of General Richard Montgomery,” by Thomas H. Montgomery, in the “New York Genealogical and Biographical Record” (July, 1871), where his relationship to the ancestral Scottish family is traced.

Page 370

Montgomery, Richard, Appletons' Cyclopædia, 1888, Vol. 4 Lodge-Pickens, page 370. (PDF)

See Also Wikisource. (PDF)

.