We speak of Montgomery County so often, and hear the name “Montgomery” mentioned so frequently, that one would suppose most every one knew for whom this important Maryland County was named. However, strange as it might seem, the writer suspects that, just the reverse is true, and that as a matter of fact, but comparatively few people could answer this question, although the Capital of the Nation itself was to an extent carved out of this county when the District of Columbia was formed, back in 1791.

With the county of Fairfax to the south of us a portion of which was retroceded to Virginia in 1846, it is quite likely that just the opposite conclusion might be drawn, for most every one seems to know that it was named for Lord Fairfax, whose American descendant today occupies a seat in the British House of Lords, and yet, why every schoolboy should not know for whom the Maryland county was named, is one of those difficult things we can not easily answer, and especially is it important that we should know this, when we consider the sacrifice made by this brave man in the interest of free government.

Up until 1748, all the territory that in that year became Frederick County, had before then been a part of Prince Georges County. However, as Frederick County soon became more populous, it was deemed expedient also to rearrange this county, and in 1776. Montgomery and Washington Counties were formed out of Frederick, though still leaving the last mentioned with sufficient area for its proper development. To Dr. Thomas Sprigg Wooton is given the credit for having introduced, in the Maryland State Legislature, a bill for the separating of Frederick County, which was finally passed on September 6, 1776, though by a small majority. This bill reads as follows:

“Resolved—That, after the first day of October next, such part of the said county of Frederick as is contained within the bounds and limits following, to wit: Beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock Creek, on the Potomac River, and running thence with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Parrs Spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning, shall be and is hereby erected into a new county called Montgomery County.”

Coming into existence as it did, during one of the most tense periods of the American Revolution, it seems quite natural that this county should have been named for that capable and brave soldier and patriot, Maj. Gen. Richard Montgomery, killed in the attempt to capture the City cf Quebec, Canada, December 31, 1775, and, by the way, we are told that this was the first county in Maryland to ignore the custom of naming towns and counties after princes, lords and dukes—as Baltimore, Frederick, Arundel and Prince George—adopting in their stead such illustrious republican names as Montgomery, Washington, Carroll, Howard and Garrett.

Montgomery's death had occurred within less than one year when the county named for him was established, and the selecting of his name proved a most fitting and sacred tribute to his memory.

Like many of the brave officers in the American Revolution, Gen. Montgomery had not resided in the colonies any considerable length of time, though, as a soldier in the British army he began his field service in Canada in 1757 and participated year later in the reduction of Louisburg, a French fortress, a veritable Gibraltar, upon which the most scientific engineering skill had been added to nature, in an effort to make it impregnable. In 1759, it is said, he shared in the glorious victory of Gen. James Wolfe at Quebec, where, during the scaling of the Heights of Abraham, that brave and gallant officer lost his life, and here, too, in the attack on Quebec in 1775, the brave Montgomery sacrificed his all for the same principles that Warren had laid down his life for at Bunker Hill, on June 17, 1775 —155 years ago last week.

Incidentally, it does seem wrong that these same principles for which our fathers fought, and for which such men as Montgomery and Warren died, should not be applied to the people of the District of Columbia. For, after all “taxation without representation” is just as unfair and unjust today as during the reign of George III; just as unfair as it was during that August day in 1774 when the good people of our own Georgetown refused to permit the brigantine Mary and Jane to discharge its cargo of tea, consigned to Robert Peter at that port.

Indeed, is it any wonder that the people of the District should feel degraded, humiliated and embarrassed at their most unfortunate plight, when such incidents as the death of Richard Montgomery—for whom a part of the very District of Columbia itself was named, whose life was sacrificed upon the altar of American freedom for the enfranchisement of the American people, when they know that they alone, of all the people of the United States are still unable to say what shall become of the money they pay in local and Federal taxes? Indeed, the people of the District almost feel like voicing Lincoln's Sentiments when he said:

“Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves: and, under a just God, cannot long retain it.”

Death of Richard Montgomery during the storming of Quebec.

But to return to the story. No truer patriot ever lived than Richard Montgomery, and no braver soldier ever sacrificed his life than did he. Born in Dublin, Ireland, on December 2, 1736—when George Washington was just four years old—he was the son of Thomas Montgomery of Convoy House, whose children included three sons, namely, Alexander, John and Richard, and one daughter. We are told that his family was “highly respectable,” and that Alexander, the first son, commanded a grenadier company in Wolfe's army, and was present at the capture of Quebec; John lived and died in Portugal, and the daughter married Lord Ranelagh.

After serving in the British army—a commission having been obtained for him in 1754, when he was but 18 years of age—he decided to abandon the king's service, and, accordingly, in 1772 sold his commission, and in January, 1773, arrived in New York, where he purchased a farm. It was here that he either became acquainted with or renewed the acquaintance of, the Clermont branch of the Livingston family. However, whichever way it may have been, we know that it was during the following July that he married the eldest daughter of Robert R. Livingston, then one of the judges of the Superior Court of the province.

From the very day that Montgomery first landed in New York, it is apparent that he became actively interested in the political affairs of the Colonies, for we find that in April, 1771, he was elected a member of the delegation from the County of Dutchess to the first provincial convention held in New York, and it was while thus serving that the National Congress commissioned him one of the eight brigadier generals provided for by that body.

Montgomery was only one of many capable Irishmen who threw in their lot with the cause of the colonists and who rendered conspicuous service in establishing American liberty. He had not sought this distinction and only accepted it as a duty he felt he owed to his adopted country. In a letter he wrote to a friend soon afterward we find him saying:

“The Congress having done me the honor of selecting me a brigadier general in their service, is an event which must put an end for awhile, perhaps forever, to the quiet scheme of life I had prescribed for myself; for, though entirely unexpected and undesired by me, the will of an oppressed people, compelled to choose between liberty and slavery, must be obeyed.”

The attack upon Quebec in which Montgomery was killed took place early on the morning of December 31, 1775. John Armstrong, his brother-in-law, who served as Secretary of War during the second administration of President Madison and who has written an excellent biography of Richard Montgomery, has this to say of that soldier's death and the incidents immediately leading up to that most unfortunate occurrence:

“A council of war was accordingly convened, and to this the general submitted two questions: ‘Shall we attempt the reduction of Quebec by a night attack? And if so, shall the lower town be the point attacked?’ Both questions having been affirmatively decided, the troops were ordered to parade in three divisions at 2 o'clock in the morning of the 31st of December; the New York regiments and part of Easton's Massachusetts Militia, at Holland House; the Cambridge detachments on Lamb's company of artilleries, with one field piece, at Capt. Morgan's quarters; and the two small corps of Livingston and Brown, at their respective grounds of parade.

“To the first and second of these divisions were assigned the two assaults, to be made on opposite sides of the lower town; and to the third, a series of demonstrations or feigned attacks in different parts of the upper.

“Under these orders, the movement began between 3 and 4 o'clock in the morning, from the Heights of Abraham. Montgomery advanced at the head of the first division by the river road, round the foot of Cape Diamond to Aunce ou Mere; and Arnold, at the head of the second, through the suburbs of St. Roque, to the Sault de Matelots. Both columns found the roads much obstructed by snow, but to this obstacle on the route taken by Montgomery were added huge masses of ice, thrown up from the river, and so narrowing the passage round the foot of the promontory, as to greatly retard the progress and disturb the order of the march.

“These difficulties being at last surmounted, the first barrier was approached, vigorously attacked and rapidly carried. A moment, and but a moment, was now employed to reexcite the ardor of the troops, which the fatigue of the march and the severity of the weather had somewhat abated. ‘Men of New York!’ exclaimed Montgomery, ‘you will not fear to follow where your general leads —march on;’ then placing himself again in the front, he pressed eagerly forward to the second barrier, and, when but a few paces from the mouths of the British cannon, received three wounds which instantly terminated his life and his labors. Thus fell, in the first month of his fortieth year, Maj. Gen Richard Montgomery.

“The fortune of the day being now decided, the corpse of the fallen general was eagerly sought for and soon found. The stern character of Carleton's habitual temper softened at the sight; recollections of other times crowded fast upon him; the personal and professional merits of the dead could neither be forgotten nor dissembled, and the British general granted the request of Leut. Gov. Cramahe to have the body decently interred within the walls of the city.

“In this brief story of a short and useful life, we find all the elements which enter into the composition of a great man and distinguished soldier: ‘a happy physical organization, combining strength and activity, and enabling its possessor to encounter laborious days and sleepless nights, hunger and thirst, all changes of weather, and every variation of climate.’ To these corporeal advantages was added a mind, cool, discriminating, energetic, and fearless; thoroughly acquainted with mankind, not uninstructed in the literature and sciences of the day, and habitually directed by a high and unchangeable moral sense.

“That a man so constituted should have won ‘the golden opinions’ of friends and foes is not extraordinary. The most eloquent men of the British Senate became his panegyrists; and the American Congress hastened to testify for him, ‘their grateful remembrance, profound respect, and high veneration.’”

Like so many accounts of events happening during the Revolutionary War, the intense excitement of the time was responsible for the different versions we find today of the death of Richard Montgomery. One account, however, that the writer feels worthy of adding to what has already been said, was published many years ago by Louise Livingston Hunt, most likely in some way related to the wife of Gen. Montgomery. This author tells us:

“It was 4 o'clock in the morning of December 31, 1775. during a violent snow-storm, that the attack on Quebec was made. The little American Army had undergone inexpressible hardships during the campaign, and the soldiers were half starved and half naked. It took all the magnetic power of Montgomery to stir them into renewed action. ‘Men of New York,’ he exclaimed, ‘you will not fear to follow where your general leads; march on!’ Then placing himself in the front, he almost immediately received the mortal wound which suddenly closed his career.

“Thus fell Richard Montgomery, at the early age of 37. Three weeks before his death he was promoted to the rank of major general. Young, gifted, and brave, he was mourned throughout the country, at whose altar he had offered up his life—apparently in vain; for fate decided the battle in favor of the British.

“The story that he was borne from the field of battle by Aaron Burr, under the continued fire of the enemy, has always been received with doubt. It may now, upon the highest authority, be pronounced to be without foundation.

“It was rumored, but not ascertained by the British for some hours, that the American general had been killed. Anxious to ascertain, Gen. Carleton sent an aide-de-camp to the seminary, where the American prisoners were, to inquire if any of them would identify the body. A field officer of Arnold's division, who had been made prisoner near Sault au Matelot barrier, accompanied the aide-de-camp to the Pres de Ville guard and pointed it out among the bodies, at the same time pronouncing in accents of grief a glowing eulogism on Montgomery's bravery and worth.

“Besides that of the general, the bodies of his two aides-de-camp were recognized among the slain. All were frozen stiff. Gen. Montgomery was shot through the thigh and through the head. When his body was taken up, his features were not in the least distorted, his countenance appeared serene and placid, like the soul that had animated it. His sword, the symbol of his martial honor, lay close beside him on the snow. It was picked up by a drummer-boy, but immediately afterward was given up to James Thompson, Overseer of Public Works and Assistant Engineer during the siege, who had been intrusted by Gen. Carleton with the interment of the body. Through the courtesy of the British general, Montgomery was buried within the Walls of Quebec, with the honors of war.”

Mrs. Hunt also tells us in an interesting way of the transferring of the remains from Quebec to New York, when the passing of the body down the Hudson, forty-three years after the death of Montgomery, was witnessed by his aged widow.

“Gov. Clinton,” according to her statement, “had directed the adjutant general, with Col. Van Rensselaer and a detachment of Cavalry, to accompany the remains to New York. They left Whitehall on the 2d of July, arriving at Albany on the 4th.

“Great preparations had been made to receive the remains with all possible splendor and eclat. The procession moved through all the principal streets of Albany, escorted by the military under arms, joined by an immense concourse of citizens. The remains were laid in state in the Capitol. In every village on the route similar honors had been paid to the memory of the gallant Montgomery.

“The skeleton had been placed in a magnificent coffin, which had been sent by the Governor. On the 6th of July, at 9 o'clock in the morning, a procession, perhaps still larger than the first, accompanied the coffin to the steamer Richmond, on board which it was put, With a large military escort.

“The boat floated down for several miles under the discharge of minute-guns from both shores. It was astonishing to observe the strong sympathies which were everywhere evoked by the arrival of these sacred remains. The degree of enthusiasm that prevailed and the patriotic feeling that evinced itself reflected credit upon the State of New York, and not a voice was heard in disapproval of the tributes of respect thus paid to the memory of this hero of the Revolution.

Gov. Clinton had informed Mrs. Montgomery that the body of the general would pass down the Hudson; by the aid of a glass she could see the boat pass Montgomery Place, her estate near Barrytown. I give her own quaint and touching terms as she describes the mournful pageant in a letter to her niece.

“ ‘At length,’ she wrote, ‘they came by, with all that remained of a beloved husband, who left me in the bloom of manhood, a perfect being. Alas! how did he return! However gratifying to my heart, yet to my feelings every pang I felt was renewed. The pomp with which it was conducted added to my woe; when the steamboat passed with slow and solemn movement, stopping before my house, the troops under arms, the Dead March from the muffled drum, the mournful music, the splendid coffin canopied with crape and crowned by plumes, you may conceive my anguish; I cannot describe it.’

“At Mrs. Montgomery's own request, she was left alone upon the porch when the Richmond went by. Forty-three years had elapsed since she parted with her husband at Saratoga. Emotions too agitating for her advanced years overcame her at this trying moment. She fainted, and was found in an insensible condition after the boat had passed on its way. Yet the first wish of her heart was realized, after years of deferred hope, and she wrote to her brother in New Orleans, ‘I am satisfied. What more could I wish than the high honor that has been conferred on the ashes of my poor soldier?” “

Speaking of Montgomery, Ramsey, in his “History of the American Revolution,” says:

“Few men have ever fallen in battle so much regretted by both sides as Gen. Montgomery. His many amiable qualities had procured him an uncommon share of private affection, and his great abilities an equal proportion of public esteem.

“Being a sincere lover of liberty, he had engaged in the American cause from principle, and quitted the enjoyment of an easy fortune and the highest domestic felicity to take an active share in the fatigues and dangers of a war instituted for the defense of the community of which he was an adopted member. His well-known character was almost equally esteemed by the friends and foes of the side which he espoused. In America he was celebrated as a martyr to the liberties of mankind, in Great Britain, as a misguided, good man, sacrificing what he supposed to be the rights of his country.

“His name was mentioned in Parliament with singular respect. Some of the most powerful speakers in that assembly displayed their eloquence in sounding his praise and lamenting his fate. Those in particular who had been his fellow-soldiers in the previous war expatiated on his many virtues. The minister himself acknowledged his worth, while he reprobated the cause for which he fell. He concluded an Involuntary panegyric by saying, ‘Curses on his virtues, they have undone his country!’ ”

For 42 years the body of Richard Montgomery remained in its original burial place, but in 1818, it was returned by a grateful people to his beloved country and to the city of New York, where it was reinterred on July 1, of that year, beneath the monument erected to his memory, in front of St. Paul's Church, near the monument erected to his memory by order of Congress, and which bears the following inscription:

“This Monument Was erected by order of Congress. 25th January, 1776, To transmit to posterity A grateful remembrance of the Patriotism, conduct, enterprise, and Perserverance of Major General Richard Montgomery; Who, after a series of successes. Amidst the most discouraging difficulties, Fell In the attack On Quebec, 31st of December. 1775, Aged 35 years.”

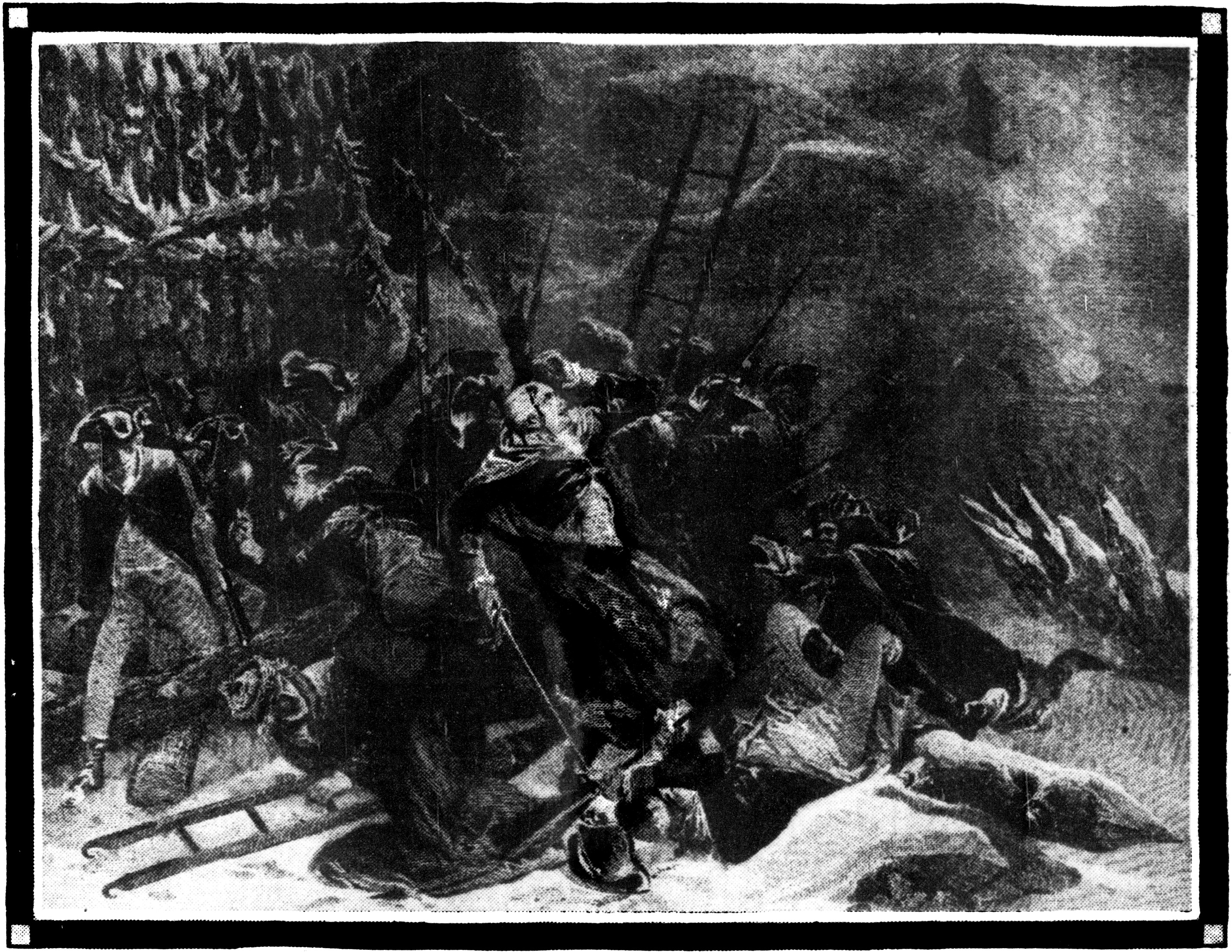

Maj. Gen. Richard Montgomery, for whom Montgomery County, Md., was, named. The sword pictured was carried by him at the storming of Quebec, December 31, 1775. It was ordered presented to Congress and deposited in the National Museum.

In the north hall of the old building of the National Museum may be seen the sword carried by Gen. Montgomery, and the silver buckles worn by him, when he was killed at Quebec.

The history of these personal articles of the brave Montgomery is peculiarly interesting. After the attack, the sword was found by a drummer boy and taken from him by James Thompson, overseer of works in the royal engineer department, who, however, was generous enough to give him 7 shillings and 8 pence for it.

In Thompson's will he bequeathed it to his nephew, James Thompson Harrower, who sold it in 1878 to the Marquis of Lome, governor general of Canada, who in 1881 presented it to Victor Drummond, esq , charge d'affairs and interim of the British legation at Washington. Mr. Drummond in turn presented it to Miss Louise Livingston Hunt, whose sister, Miss Julia Barton Hunt, in 1923, presented it to the Nation. It was gratefully accepted by joint resolution of Congress, adopted on Washington's birthday, February 22, 1923, the substance of which reads:

“Resolved, etc., that the sword of Gen Richard Montgomery, which he wore when he fell at the siege of Quebec, on December 31, 1775, be accepted in the name of the Nation from the donor, Miss Julia Barton Hunt, whose generosity is deeply appreciated, and that the sword be deposited In the National Museum.”

The silver buckles were presented to the National Museum by Return Jonathan Meigs 4th. After the death of Montgomery, they came into the possession of the lamented general's friend. Col. Return Jonathan Meigs and descended to the donor.

One could hardly be expected to write a history of so notable a county as is Montgomery in a magazine article, and any attempt to do so would most likely prove unsatisfactory. However, there is much to be said to its credit and its praise, and. since its formation in 1776, it has proven to be one of the strongest vertebrae in the backbone of our American Republic.

During the war of the American Revolution, though then one of the infant counties, yet it contributed its full share and more in man power and money, for the achievement of independence, and wherever the Maryland line went, Montgomery County was well represented. Indeed, Scharf, in his “History of Western Maryland,” gives us the names of the following persons as having become members of the Society of the Cincinnati at the close of the Revolutionary War; C. Ricketts, lieutenant; Lloyd Beall, captain; Samuel B. Beall, lieutenant; Henry Gaither, captain; Richard Anderson, captain; James McCubbin Lingan, captain; Richard Chiderson, captain; David Lynn, captain. In addition to the members of that society, there were Cols. Charles Greenbury Griffith and Richard Brooke, Capts. Edward Burgess and Robert Briscoe. Lieuts. Greenbury Gaither, John Gaither, Elisha Beall, Elisha Williams, John Lynn and John Court Jones. Ensigns Thomas Edmondson, John Griffith and William Lamar, and Quartermaster Richard Thompson.

In all the wars subsequent to the American Revolution, Montgomery County performed its part with a patriotism and devotion unsurpassed by any other part of the country. Being so very close to the Federal Capital, it shared In its scares during the Civil War, and during the raid on Washington in July, 1864, culminating in the battle of Fort Stevens, much damage was done by the Confederate forces just north of the city in Maryland.

Here several houses were destroyed, including that of Montgomery Blair, father of my esteemed friend, Maj. Gist Blair, and Postmaster General in Lincoln's cabinet, and who was named for Richard Montgomery. As much cattle and stock as was needed by the opposing army was also taken, sometimes without even compensating the owners with the customary Confederate money. A diary kept by a member of the Brooke family, of Fallen Green, near Sandy Spring, tells us of some anxious hours during Early's advance on Washington. Under date of July 12, the chronicler says:

“This morning, Charles was Just sending his horses out to the reaper, all were up by the pump except Snap, when two Confederates came dashing up the road, passed by without stopping except to say something about the horses. John Cook was taking them down the lane as fast as he could, they followed. Charles stood waiting. Eliza had Coma and Puss brought up to the front steps, where she held them (Hannah had gone over to the neighbor's). I had my chair out on the porch; we did not wait long till we saw them come back with Charles' three work horses. Charles stayed out and talked with them awhile. One went first in the stables and examined them, then C. told where Snap was, he went out in the field to look at her (she is in a dreadful condition with the ( (_____(?) evil). While he was gone, the other hitched his horses and came walking up the front yard where Eliza stood, he spoke very pleasantly, and, though very much sunburnt and soiled, was a handsome man and had such a pleasant, good expression that I began to hope directly that we should succeed In keeping our horses. We did so, and though they had been directed here, with the information that Charles had line carriage horses and a riding horse besides, and rather questioned at first his assurances to the contrary, yet, after staying here fully half an hour, perhaps longer, they talked together a few minutes and we overheard the conclusion that none of these horses would answer their purpose at all; all were therefore left much to our satisfaction.

“The handsome man was Capt. Fulton from Port Tobacco, Md. He said he had run away from school to join the army. Eliza said. ‘What a pity you did not run to the right side.’ He looked at her with the brightest smile and said he thought he had done so. Charles asked if he knew Ridgley Brown. ‘Yes indeed.’ said he, looking quickly. ‘He was our colonel, we are of the 5th Maryland Regiment. Yes. I was near him when he was killed. He was shot in the head and died in about an hour after. He was a magnificent officer, brave as a lion, very much beloved and had been twice complimented in the field by the general.’ He continued. ‘He was too brave for he often exposed himself unnecessarily.’—etc. etc.

“Charles mentioned to him some of his schoolmates from Port Tobacco. He knew them well—knew Marcus Duval, too. John Kabler came while they were here and seemed quite fascinated with this one. They had a great deal of talk, about the differences of opinion on the two sides; John and Charles expressing without any reserve, theirs, as he did his, and he said he felt far more respect for and confidence in such as owned their sentiments and stood firmly to them, than such as were afraid, or were anything to anybody to suit their own purposes.

“A great force of Confederates are concentrateing around this side of Washington, but what seemed to me the most alarming news was that Mosby was said to be in Rockville with 800 of his guerrillas, of whose unprincipled lawlessness I have more dread than of anything else we could be subjected to. We heard also, with sorrow and indignation, of dear Cousin Benjamin's treatment from some of the Confederates—after saving his horse once—he was riding to Olney when he met some, who demanded his horse and on his positively refusing to give it up, they ungirded his saddle and dragged him off. He went afterward to Bradley Johnson, who was their commander, but could obtain no redress—he said his lieutenant's horse had given out and he must have another. Oh, it was too hard for him to lose Andy.”

It is apparent that the Confederate forces did not receive much voluntary assistance from the people of Montgomery County, Md.

There are too few monuments in this country to Richard Montgomery. Is there one in Montgomery County? If not, why not?