The Southern Bivouac, Volume II, No. 8, January, 1887.

Theodore O'Hara

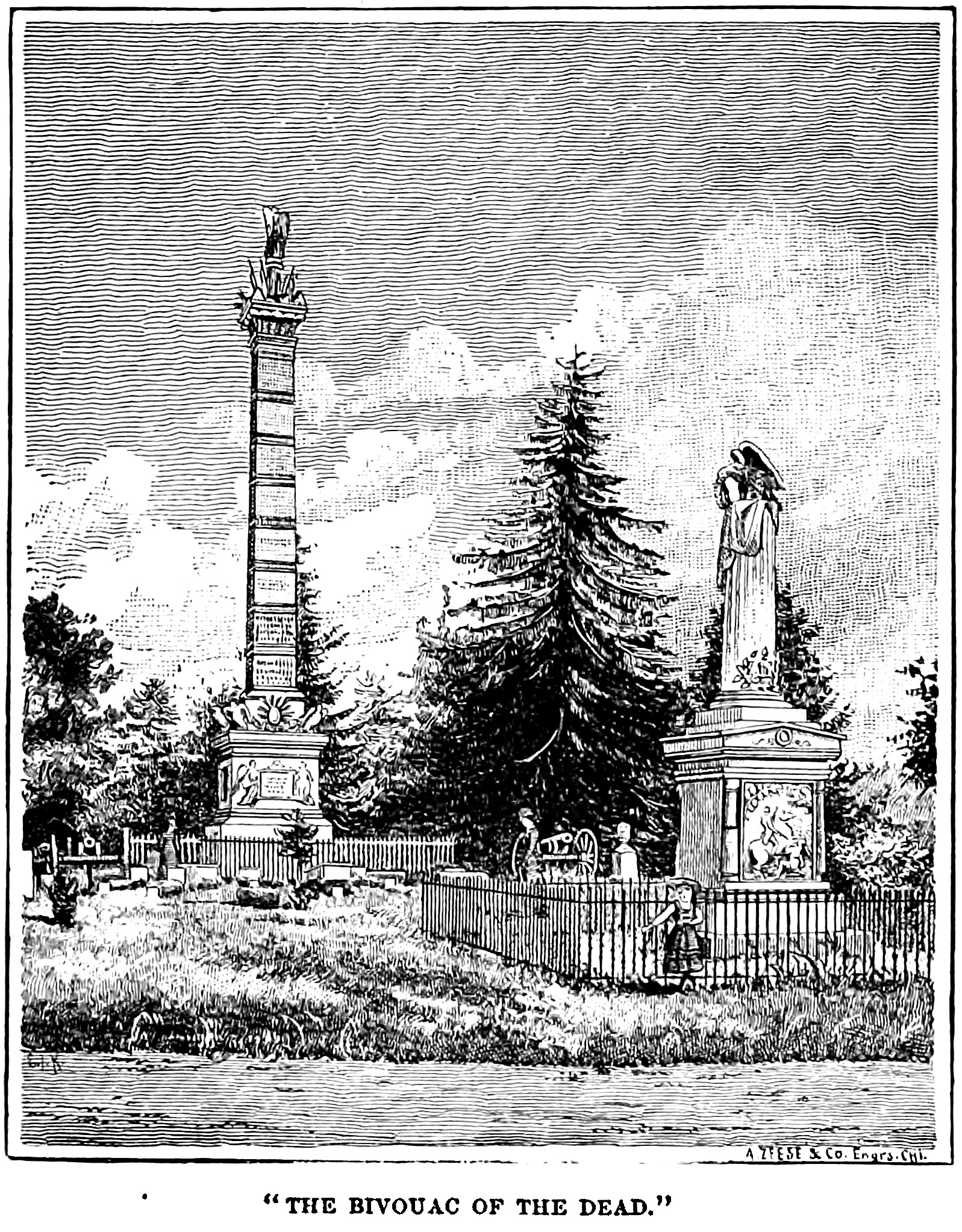

THEODORE O'HARA the author of that deathless elegy, “The Bivouac of the Dead,” rests from his labors in the cemetery at Frankfort, Ky. Above the modest marble slab that holds no record of his fame, or deeds in battle or in song, a rose-bush, planted there by a good woman's kindly hand, blossoms into sweet flowers that shed their petals on his grave. Ranged about his tomb in concentric circles sleep other brave hearts that beat their lives out in battle for their country. Towering in its carven beauty to the summer skies stands near his tomb the monument erected by the State to the memory of the Kentuckians who were killed in the Mexican war. O'Hara wrote “The Bivouac of the Dead” to these defenders of the nation. It is very probable that it was written in the cemetery, and that the poet found in that beautiful retreat the inspiration necessary for his work. The poem appears in the Louisville Courier, Sunday, June 24, 1860 with the introduction:

Lines written at the tomb of the Kentuckians who fell at Buena Vista, buried in the cemetery at Frankfort.

Mr. Edward Hensley of Frankfort, was a warm personal friend of O'Hara's, and recalls many interesting incidents in his life. It is his belief that O'Hara read the poem for the first time in a saloon, which was located on the street facing the State House. A rollicking party of his young friends were the auditors, and it was pronounced at the time a great poem.

“The Bivouac of the Dead” was written in August 1847. The original poem contained twelve stanzas; as published in “O'Hara and his Eligies,” a valuable little volume, compiled by G.W. Ranck, of Lexington. Ky., it contains but nine verses. After careful examination of all the records and circumstances bearing on the subject, the writer of this article believes that the poem as printed by Mr. Ranck's volume is the most authentic; it contains a number of errors, but all evidently made in copying.

Mrs. Mary O'Hara Price, the poet's sister, who, at the period which she writes, was living near Frankfort, but is now dead, wrote the following letter to Mr. Ranck:

November 23, 1875.

G.W. Ranck:

My Valued Friend— I was pained exceedingly a few days since by reading in the Louisville Commercial a criticism, amounting almost to an accusation, upon that very beautiful work, “O'Hara and his Elegies,” undertaken an brought forward by you as an agreeable pastime for you own leisure hours, and for the delight of attached friends and relatives of my brother Theodore. I am surprised that any thing so pure and beautiful should have elicited remarks so severe, not to say acrimonious. I can but hope the correspondent of the Commercial meant no harm. To him and to all others I will say that I furnished you with the poem, “The Bivouac of the Dead,” as I found it upon my return to Kentucky, after an absence of many years in a distant state; and if it is not as it came first from Theodore's hand, surely you are not answerable. Consciousness of the pleasure you have given to many hearts should outweigh the little bitterness that has been dropped into your cup. Besides, you have done a great service to the literature of our State by rescuing from the fleeting existence of newspaper life, two poems so much admired and approved.

With the highest confidence and affection,

Your Friend,

Mary O'H. Price

Here is a letter from Mr. Ranck on the same subject.

In answer to your favor of yesterday, I have to say that I obtained the text of “Bivouac of the Dead,” as published by me in 1875, directly from the hands of the poet's sister, Mrs. Mary O'Hara Price, now deceased.

You ask about Mrs. O'Hara? Theodore O'Hara never married.

A second edition of “O'Hara and his Elegies” I have never published.

You ask, “Did you vary the text?” Of course not. I never added to it, took from it, changed, or amended it “one jot or one tittle,” but published it exactly as Mrs. Price sent it to me. The elegy, as first written in 1847, comprised twelve stanzas, while the one sent to me by the scholarly sister of O'Hara consisted of but nine stanzas. A number of versions, nearly all differing in some particular, had been published. Believing that the various versions bore evidence of the poet's own amendments and corrections (typographical errors excepted) and that the abbreviated text sent me by Mrs. Price was sent as the most complete of them all, I published it.

Mrs. Price, as the sister of the poet, was not only watchful of his fame, but by her culture, scholarship, and keen poetic instinct knew how to protect it. She sent me just what she meant to send, and what she desired to have accepted.

The following copy is made from Mr. Ranck's volume, but I have taken the liberty of correcting all the palpable errors:

THE BIVOUAC OF THE DEAD.

The muffled drum's sad roll has beat

The soldier's last tattoo.

No more on life's parade shall meet

The brave and daring few.

On Fames eternal camping-ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards with solemn round

The bivouac of the dead.

No answer of the foe's advance

Now swells upon the wind;

No troubled thought at midnight haunts

Of loved ones left behind;

No vision of the morrow's strife

The warriors dream alarms;

No braying horn nor screaming fife

At dawn shall call to arms.

Their shivered swords are red with rust,

Their plumed heads are bowed;

Their haughty banner trailed in dust

Is now their martial shroud.

And plenteous funeral tears have washed

The red stains from each brow,

And their proud forms in battle gashed

Are free from anguish now.

The neighing steed, the flashing blade,

The trumpet's stirring blast,

The charge, the dreadful cannonade,

The din and shout are past;

Nor war's wild note, nor glory's peal,

Shall thrill with fierce delight

Those breasts the never more shall feel

The rapture of the fight.

Like the dread northern hurricane

That sweeps his broad plateau

Flushed with the triumph yet to gain

Came down the serried foe,

Our heroes felt the shock, and leapt

To meet them on the plain;

And long the pitying sky hath wept

Above the gallant slain.

Sons of our consecrated ground,

Ye must not slumber there,

Where stranger steps and tongues resound

Along the heedless air.

Your own proud land's heroic soil

Shall be your fitter grave;

She claims from War his richest spoil—

The ashes of her brave.

So 'neath their parent turf they rest,

Far from the gory field;

Borne to a Spartan mother's breast

On many a bloody shield;

The sunshine of their native sky

Smiles sadly on them here,

And kindred hearts and eyes watch by

The heroes' sepulcher.

Rest on, embalmed and sainted dead!

Dear as the blood you gave,

No impious footsteps here shall tread

The herbage of your grave;

Nor shall your glory be forgot

While Fame her record keeps,

Or Honor points the hallowed spot

Where Valor proudly sleeps.

Yon marble minstrel's voiceful stone

In deathless songs shall tell,

When many a vanished age hath flown,

The story how ye fell;

Nor wreck, nor change, or winter's blight,

Nor Time's remorseless doom,

Shall dim one ray of holy light

That gilds your glorious tomb.

I have made but two changes in Mr. Ranck's version. In the first line of the last verse,

“Yon marble minstrel's voiceless stone.”

has been made to read “voiceful stone.” There is no such thing as a “voiceless tone.” In the copy printed in the Louisville Courier, in 1863, “voiceful stone” is used. It may have been originally written so, but O'Hara had to fine an appreciation of the value of words to allow it to remain so.

“yon marble minstrel's voiceful stone”

would make the poet speak of marble stone, but as it is the least objectionable of the three different phrases used I have let it stand.

The third line of the last verse in Mr. Ranck's copy reads:

“When many a vanquished age hath flown.”

The proper word there is “vanished;” evidently the mistake was made in copying, and I have changed it to “vanished.”

The poem, as before stated, was written in 1847, and this copy, furnished Mr. Ranck by O'Hara's sister, was made fully twenty years later. The poet was constantly changing, revising, and polishing his great work.

In the Louisville Courier copy (1860) the following verses appear, but were afterward eliminated:

Like the fierce northern hurricane

That sweeps his great plateau,

Flushed with triumph yet to gain,

Came down the serried foe;

Who heard the thunder of the fray

Break o'er the field beneath,

Knew well the watchword of that day

Was victory or death.

Long did the doubtful conflict rage

O'er all that stricken plain,

For never fiercer fight did wage

The vengeful blood of Spain.

And still the storm of battle blew,

Still swelled the gory tide—

Not long out stout old chieftain knew

Such odds his strength could bide.

'Twas at that hour his stern command

Called to a martyr's grave

The flower of his own loved land,

The nation's flag to save.

By rivers of their father's gore

His first-born laurels grew,

And well he deemed the sons would pour

Their lives for glory too.

In 1863 the poem again appeared in print, with numerous changes that no one but O'Hara would have made. The line

“That sweeps his great plateau”

is made to read

“That sweep his broad plateau”

Several other words of minor import are also replaced by words that, while not affecting the sense of rhythm of the poem, strengthen it materially.

In the eighth verse in the 1860 publication, but which does in Ranck's copy, the lines

“Alone awake each solemn height

That frowned over that dread fray,”

is altered to read “sullen” a decided improvement.

The three verses given above were used in both the 1860 and 1863 copies, but in the copy furnished by O'Hara's sister they do not appear. Leaving out these verses, which are purely descriptive, makes the poem a perfect elegy. If there was any doubt that O'Hara himself erased them, it must be silenced by the reconstruction of the fifth verse. In the editions of 1860 and 1863 it reads:

“Like the fierce northern hurricane

That sweeps his broad plateau,

Flushed with the triumph yet to gain,

Came down the serried foe;

(Who heard the thunder of the fray

Break o'er the field beneath,

Knew well the watchword of the day

Was ‘Victory of death!’)”

The last for lines of this verse are very weak, and O'Hara seemed to recognize it did not reach the general standard of the elegy. He takes the third and fourth line of the eighth verse of the original publication, write two new lines to complete the quatrain, and inserts it as follows, in place of the last four lines in parenthesis above. The two lines in italics are all that are saved of the three rejected verses:

“Our heroes felt the shock, and leapt

To meet them on the plain;

And long the pitying sky hath wept

Above the gallant slain.”

The above is a careful revision of “The Bivouac of the Dead,” and I believe it to be as authentic as it is possible to make it.

The only other poem of O'Hara's that Mr. Ranck has been able to discover is “The Old Pioneer,” a tribute to Daniel Boone. It was written after “The Bivouac of the Dead,” but does not approach that inspired composition, although no doubt the success of the martial elegy tempted O'Hara to repeat, if possible, that wonderful achievement. It will be interesting to compare the two poems.

THE OLD PIONEER.

A dirge for the brave old pioneer!

Knight-errant of the wood!

Calmly beneath the green sod here

He rests from field and flood;

The war-whoop and panther's screams

No more his soul shall rouse,

For well the aged hunter dreams

Beside his good old spouse.

A dirge for the brave old pioneer!

Hushed now his rifle's peal;

The dews of many a vanished year

Are on his rusted steel;

His horn and pouch lie moldering

Upon the cabin-door;

The elk rests by the salted spring,

Nor flees the fierce wild boar.

A dirge for the old pioneer!

Old druid of the West!

His offering was the fleet wild deer

His shrine the mountain's crest.

Within his wildwood's temple space

An empire's towers nod

Where erst, alone of all his race

He knelt to Nature's God.

A dirge for the brave old pioneer!

Columbus of the land!

Who guided freedom's proud career

Beyond the conquered strand;

And gave her pilgrim sons a home

No monarch's step profanes,

Free as the changeless winds that roam

Upon its boundless plains.

A dirge for the brave old pioneer!

A dirge for his old spouse!

For her who blest his forest cheer

And kept his birchen house.

Now soundly by her chieftain may

The brave old dame sleep on,

The red man's step is far away,

The wolf's dread howl is gone.

A dirge for brave old pioneer!

His pilgrimage is done;

He hunts no more the grizzly bear

About the setting sun.

Weary at last of chase and life

He laid him here to rest,

Nor recks he now what sport of strife

Would tempt him further west.

A dirge for the brave old pioneer!

The patriarch of his tribe!

He sleeps—no pompous pile marks where,

No lines his deeds describe.

They raised no stone above him here,

Nor carved his deathless name—

An empire is his sepulcher,

His epitaph is Fame.

[Note. — The last stanza of this ode was written before Boone's monument had been erected.]

Mr. Rank was greatly surprised at the existence of the following exquisite bit of verse, which I have no doubt O'Hara is the author of. Mr. Edward Hensley, of Frankfort, informed me that he had heard O'Hara recite it a number of times, and was positive that he wrote it.

SECOND LOVE.

Thou art not my first love,

I loved before we met,

And the memory of that early dream

Will linger round me yet;

But thou, thou art my last love,

The truest and the best,

My heart but shed its early leaves

To give thee all the rest.

Mr. Hensley also says that O'Hara is the author of that rollicking rhyme which is quoted even to this day, a stanza of which runs:

“I'd life for her,

I'd sigh for her,

I'd drink the river dry for her—

But d—d if I would die for her.”

Mrs. Mary O'Hara Price, the poet's sister, was constant in her expression of gratitude to Mr. Ranck, and in her letters to him she always refers to his kindness.

October 6, '75

Mr. G. W. Ranck:

Dear Friend—Your last great kindness has stirred anew the foundations of my heart, and diffused the most pleasing emotions through my whole being. Your unvarying kindness has evoked many agreeable sensations, and interpreted for me many thoughts and expressions which I had read and heard, and passed by as almost meaningless, but now recur with all their real import. You have taught me that gratitude is a divine sentiment emanating from the Fountain of all Good, and I thank our Father, who has raised up to me in my old age, when nearly all my compeers have departed, a youthful friend to beautify my life, as a young vine in the forest is seen to creep over the scathed and blackened stump, decking it in lively green and hiding its unsightliness from passers-by. I thank God, and I thank you.

What a beautiful book you have made of your little “primer”—to me a folio—and the picture is perfect. When they came I did not start, I did not weep. I felt as I think I will feel when the angel shall unbar the gates of heaven when I go to join the happy throng that awaits us. I hope there is not presumption in the thought; it came of itself. Every feeling and recollection awakened was happy, “a little sad because they had been sweet.” But altogether most delightful, and I owe it all to you.

I do not know of any other poems of Theodore's. I remember of his taking away with an old portfolio filled with all manner of pieces, printed and in manuscript, but what they were I do not know. I was gone from Kentucky, living in the dear South, for many years, and returned to be with him only a few months, and to see him depart to join our patriot army. I was with him in your city when General Breckinridge made his last speech before he stepped across that chasm, that abyss that divides us forever from our foes. I wrote to our friends in the South, in a vain endeavor to obtain the old portfolio. All went when we lost all. Oh, the sorrows! the sorrows! but let us draw a veil.

* * * * * *

We will meet some day. Till then God bless you and yours.

Mary H. Price.

Mr. G. W. Ranck is the president of the Chamber of Commerce, at Lexington, Kentucky. The world of letters is indebted to him for preserving O'Hara's poems and perpetuating his fame. Although Mr. Ranck never met the poet, his interest in literature and his admiration for the genius that shone so brilliantly in “The Bivouac of the Dead” impelled him to the compilation of the little volume which has been invaluable in the preparation of this article. Mrs. Price was sorely grieved the Governor did not appoint Mr. Ranck to read “The Bivouac of the Dead” when her brother's remains were interred in the cemetery in Frankfort, and laments it frequently in her letters.

In closing this review, I quote a portion of Mr. Ranck's sketch of O'Hara's life:

Theodore O'Hara was born in Danville , Kentucky, February 11, 1820. He was the son of Kane O'Hara, an Irish political exile, noted for his piety and learning, who had been invited to Danville to take charge of an academy about to be established there under the auspices of Governor Shelby. His ancestors becoming subjected to the disabilities imposed upon Catholics in their unhappy land, abandoned home rather than religion, emigrated to this country with Lord Baltimore, and aided in founding that colony which was so long an asylum for victims of religious intolerance. The family removed from Danville to Woodford County, where the father himself commenced the education of his son. They subsequently settled in Frankfort, where several members of the family still reside.

Theodore O'Hara was remarkable when but a child. Study was his passion. It engrossed his entire boyhood, and added fuel to the fires of his genius. Happily, he was trained and appreciated by one who fully understood the nature he was molding. His education was conducted wholly by his father until he was prepared to enter college, and then that ripe scholar had so thoroughly done his work that he was at once admitted to the senior class of St. Joseph's Academy at Bardstown. There among the learned clergy of his church, he soon became pre-eminent as a profound and accomplished scholar, especially in the ancient classics; and though but a youth, the rare compliment was paid him of election to the professorship of the Greek language. He bade farewell to his Alma Mater, on graduating, in a speech so full of eloquence never to be forgotten by those who listened enraptured to it.

After leaving college he studied law in the office of Judge Owsley, where he was a fellow-student of General John C. Breckinridge, and the strong attachment there formed between the young men lasted through all his subsequent life. In 1845 he held a position in the Treasury Department at Washington, under General John M. McCalla, but his life from this this time till its close was obscured by the same dark clouds of misfortune and disappointment that seem so strangely to hung round the pathway of genius— the pressure of a narrow fortune combined with the aspiration of a noble ambition conspired to make his life erratic. He was appointed to a captaincy in the “old” United States Army, when such a position was a sure indication of merit, served with distinction through the Mexican war, and was brevetted major for gallant and meritorious conduct. He left the army at the close of the war, enriched only in reputation, and immediately commenced the practice of law in Washington City, where he remained until the breaking out of the Cuban fever, when, with many other gallant Kentuckians, he embarked in that ill-fated enterprise. He commanded regiment in the disastrous battle of Cardenas, and was badly wounded.

During the absence of the Hon. John Forsythe Minister to Mexico, Colonel O'Hara conducted the Mobile Register, as editor-in-chief, with signal ability and success. He was subsequently editor of the Louisville Times, and afterward of the Frankfort Yeoman. He was frequently called on by the government to conduct diplomatic negotiations of importance with foreign nations, and his services were specially valued in the Tehuantepec-grant business. In 1854, when the remains of the distinguished statesman, Hon. William T. Barry, arrived from Liverpool and were reinterred in the State Cemetery at Frankfort, Colonel O'Hara was the orator of the occasion, and delivered an oration so chaste and appropriate, and so full of pure and lofty eloquence, as to entitle it to a place among the best specimens of American oratory.

At the beginning of the late war his heart swelled with sympathy for the people he had always loved so well, and his sword at once unsheathed in defense of the South. He was immediately honored with an important position, and was soon promoted to the colonelcy of the Twelfth Alabama regiment. He subsequently served on the staff of General Albert Sidney Johnston, stemmed with him the fiery flood of Shiloh, and received his great chief in his arms when he fell on that ensanguined field. He was also chief of staff to General John C. Breckinridge.

The close of this war found him without a dollar. He went to Columbus, Georgia, and engaged in the cotton business with a relative; but misfortune again overtook him, for he and his partner lost all by fire. Undismayed he retired to a plantation on the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee, near a place called Guerrytown, and there he was laboring successfully when he was attacked with bilious fever, of which died Friday, June 6, I867. He received the sacrament of his church from the hands of a pious clergyman; and as the soft Southern breeze bore to him the songs of birds and odor of sweet flowers, the soldier-poet fell asleep calmly, hopefully, and resigned.

His remains were taken from Barbour County, Alabama, to Columbus, Georgia, and there buried in consecrated ground, where he slept until the State upon which his genius had been reflected proudly claimed his ashes. In the summer of 1874, in accordance with a resolution of the Kentucky Legislature, all that was mortal of the poet was brought to Frankfort; and on the 15th of September of that year his remains, together with those of Governors Greenup and Madison and several distinguished officers of the Mexican war, were reinterred with appropriate ceremonies in the State Cemetery.

O'Hara was never married. In personal appearance he was strikingly handsome. He was not quite six feet in height, very graceful and erect in his carriage, and scrupulously neat in his dress.

Theodore O'Hara sleeps his last sleep by the side of his old comrades, under the shadow of the monument erected in their honor, and amid the scenes consecrated by his genius. It is well; for that beautiful spot was his favorite haunt, he loved its soothing solitude; it there the harp-strings of his soul gave forth their sad but immortal notes, and it seems fitted by nature for a poet's tomb.

Daniel E. O'Sullivan.

Theodore O'Hara, by Daniel E. O'Sullivan, The Southern Bivouac, Volume II, No. 8, January, 1887. (PDF)