Page 606.

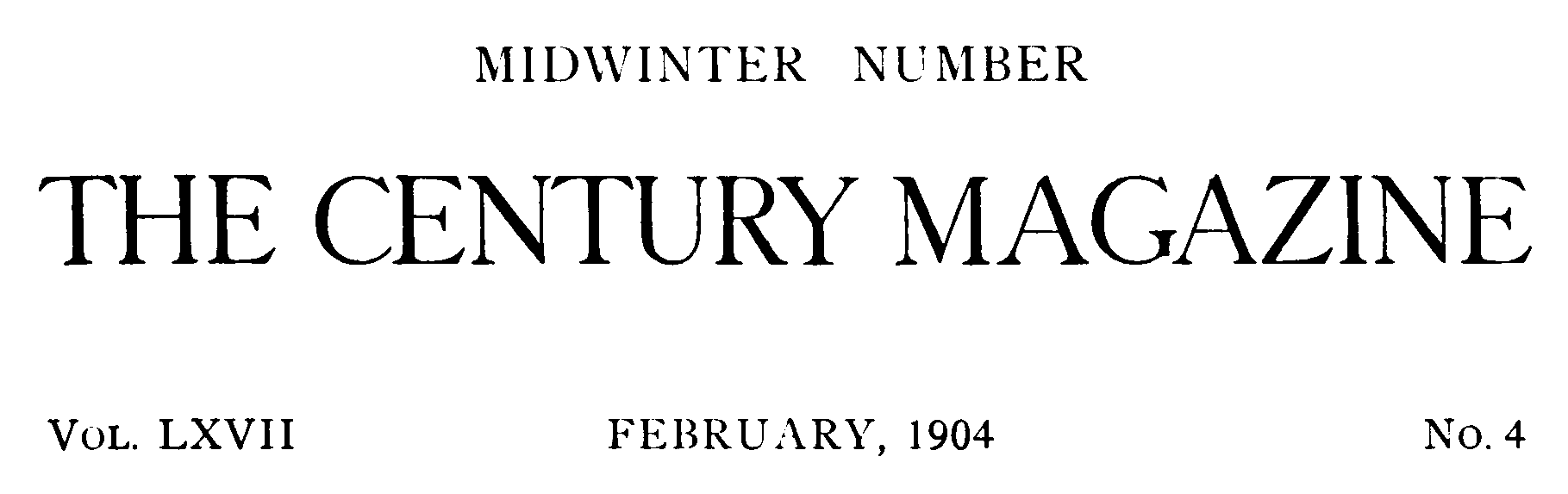

Painted in 1797 by Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick

After the Original Painting, owned by Judge James Alfred Pearce

Page 627.

The Last Portrait of Washington, and the Painter of It

We present to the readers of THE CENTURY on page 606 a copy of an original oil-portrait of General Washington, which is now for the first time introduced to the notice of the general public. The portrait was painted from life by Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick of Alexandria, Virginia, in 1797, and our representation is taken from an excellent photograph of the original made by Getz of Baltimore. In size the portrait is about fourteen by sixteen inches; it is in an excellent state of preservation, the colors being still fresh and bright, and is surrounded by a beveled gilt frame about two inches wide, which shows the marks of age and is believed to be the original one in which the picture was placed.

The artistic merits of the painting have been pronounced by competent critics to be of a high order, and the tradition is that it was considered by his family and intimate friends an excellent likeness of the general in his later years. Certainly any one must be struck by its marked resemblance to the Houdon bust and the Sharpless crayon (the latter made in 1796), which are generally recognized as giving the best likeness of Washington, and must note the strength and firmness of character and the intellectuality shown by it, qualities which seem strangely absent in many of even what are considered the best portraits of him. The artist most assuredly had skill, and his intimacy at Mount Vernon and frequent association with his subject gave him opportunities to know the man and portray him as he was.

Dr. Dick was one of the most distinguished physicians and surgeons of his day, and, in addition to his large individual practice, was greatly sought in consultation by other physicians, and, together with Dr. Craik and Dr. Gustavus R. Brown, was in attendance upon General Washington in his last illness. In addition to his professional distinction, he was accomplished in other directions also, and it is on record that “he displayed great skill, in painting in oil, and in music,” while his extensive library showed how wide was the scope of his literary activity This portrait was painted for Washington himself, and was hung at Mount Vernon; and Washington directed that, at his death, it should be returned to Dr. Dick, together with the hunting-horn he was accustomed to use. At Dr. Dick's death the portrait and hunting-horn were retained by his widow during her life, and at her death became the property of her grandson, the Hon. James Alfred Pearce, United States senator from Maryland, by whom they were bequeathed to his son, the present Judge James Alfred Pearce of the Court of Appeals of Maryland.

It is understood that Judge Pearce has made provision that, at his death, both the portrait and the hunting-horn shall be placed in the Maryland Room at Mount Vernon.

Perhaps a further short account of the distinguished artist to whom we are indebted for what is believed to be the very last picture of General Washington—and, in the opinion of many who have seen it, one of the best—may not be amiss, especially in view of the prominent part played by him in the last illness of his distinguished friend and patient.

Dr. Dick was the son of Archibald and Mary (Bernard) Dick, and was born near Chester, Pennsylvania, March 15, 1762; he died in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1825. He was educated at Pequea Academy and by private tutors, and in 1780 began the study of medicine, first in the office of Dr. Benjamin Rush, and afterward in that of Dr. William Shippen, while attending the Medical College in Philadelphia, from which in due course he received his degree. He settled in Alexandria, where he practised his profession, attaining the highest rank. A profile portrait of him by St. Memin, now in the possession of Judge Pearce, represents him as a remarkably handsome man, of strong and well-formed physique.

When Washington was first stricken with the malady which caused his death, Dr. Craik was called in. Dr. Craik was a neighbor and had been Washington's lifelong friend and companion in the army, dating from the Braddock expedition and continuing during the Revolutionary War. Recognizing the seriousness of the case, after bleeding, more than once repeated (the accepted method of treatment in those days), had failed to produce favorable results, Dr. Dick was summoned from Alexandria, and Dr. Gustavus R. Brown from Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland.

Dr. Brown was the most renowned physician of his time, south of Philadelphia. His father was a distinguished physician before him, and both were graduates of the University of Edinburgh. While attending that university, and again in work in the London hospitals, Dr. Brown (the younger) was a fellow-student and friend of Dr. Benjamin Rush, who expressed the highest opinion of his ability and attainments. His office was filled with students from Maryland and Virginia, and in addition to his professional activity he was prominent in all the affairs of the colony and State. His preéminence is well known to all acquainted with the annals of the medical profession of those days.

It is not my purpose to review the much-discussed question of the professional treatment to which General Washington was subjected in his last illness, and this short sketch of Dr. Brown is given simply to emphasize the value of his opinion and testimony in a most remarkable tribute paid by him to Dr. Dick.

General Washington died December 14, 1799, and on January 2, 1800, Dr. Brown wrote as follows to Dr. Craik:

“I have lately met Dr. Dick again in consultation, and the high opinion I formed of him when we were in conference at Mount Vernon last month concerning the situation of our illustrious friend has been confirmed. You will remember how, by his clear reasoning and evident knowledge of the causes of certain symptoms, after the examination of the General, he assured us that it was not really quinsy, which we supposed it to be, but a violent inflammation of the membranes of the throat, which it had almost closed, and which, if not immediately arrested, would result in death. You must remember he was averse to bleeding the General; and I have often thought that if we had acted according to his suggestion when he said “he needs all his strength—bleeding will diminish it,’ and taken no more blood from him, our good friend might be alive now; but we were governed by the best light we had; we thought we were right, and so we are justified.”1

We believe it is now generally accepted by physicians that the malady which proved fatal to Washington was diphtheria, and it would seem from this letter to have been correctly diagnosed as such by Dr. Dick, in opposition to the opinion of other attending physicians, although that name for the disease was not then known.

It is stated by Dr. Toner in a sketch by him, reported in the “Transactions of the Medical Society of Virginia,” that Dr. Dick proposed an operation to relieve the patient, which was not assented to by his colleagues. However this may be, it must be acknowledged that this letter of Dr. Brown, who was himself facie princeps in the profession, is a splendid tribute to the professional skill and wisdom of Dr. Dick. At the same time, what a striking memorial it is to the honorable and magnanimous character and the greatness of mind of its author, who could thus acknowledge his own mistake and give credit for the superior wisdom of his colleague!

J. Upshur Dennis.

1 Ford's “Writings of Washington,” Vol. XIV, p. 257, note.